Crows (7 page)

Authors: Candace Savage

A frog, sitting in a gutter, talks its way out of being eaten by a crow, in this illustration of a Tibetan folktale.

A frog, sitting in a gutter, talks its way out of being eaten by a crow, in this illustration of a Tibetan folktale.Fortunately, for X-treme birders like McGowan, getting there is half the fun. A few years ago, he remembers finding himself at the top of a crow-nest tree, a tall white spruce with brittle branches and a divided top. “There I was, a good 18 meters [60 feet] above ground,” he recalls, “with one foot on each trunk, measuring nestling crows. It was a windy day and things were really whipping around. I looked down at the ground and thought, ‘I am getting zero adrenalin out of this. Is that a good thing or a bad thing?’ I’m still not sure.” But when friends tell him that he needs a new hobby, he doesn’t listen to them. Catching crows is not a pastime for him. “We’re working to

understand the social behavior of an extraordinarily common bird about which surprisingly little is known,” he says. “We’re trying to get something accomplished.”

TO HELP OR NOT TO HELPunderstand the social behavior of an extraordinarily common bird about which surprisingly little is known,” he says. “We’re trying to get something accomplished.”

The ties that bind in a family of birds generally do not bind for long. Although mates often form long-lasting relationships—pairs of crows, for example, may remain together for years or until parted by death—parents and their offspring usually associate with one another for only a few months. As soon as the young are able to fend for themselves, they fly away, never to be seen again, in an annual reenactment of the empty-nest syndrome. (Curiously, female birds generally move farther afield than young males do, reversing the dispersal trends that are typically seen among mammals.) This pattern is found in at least 95 per cent of all living birds, including many species of crows—the majority of common and Australian ravens, for example, as well as fish crows, jackdaws, and rooks, among others.

But what keeps the researchers hard at work are the exceptions to the rule, the 2 or 3 percent of bird species that routinely breed in cooperative, family-based groups. Because crows are so ridiculously hard to study, nobody knows exactly how many species belong in this category, but the number is expected to keep growing. New Caledonian crows, for example, are probable candidates for inclusion, though these birds are so elusive—shimmering shadows

that melt into the darkness of the tropical canopy—that they are difficult to see, much less to study. So far, after a dozen years of effort, biologist Hunt and his small band of intrepid jungle explorers have found only a handful of nests. So much for understanding the birds’ social behavior! Yet the researchers are intrigued by the interactions they glimpse at feeding stations, where juveniles—young of the year that are clearly capable of feeding themselves—nonetheless beg from adults, presumably their parents, who obligingly cough up food for them. This observation suggests that, even after they attain independence, juvenile New Caledonian crows may stay with Mom and Dad, a behavior that strongly suggests a cooperative system.

that melt into the darkness of the tropical canopy—that they are difficult to see, much less to study. So far, after a dozen years of effort, biologist Hunt and his small band of intrepid jungle explorers have found only a handful of nests. So much for understanding the birds’ social behavior! Yet the researchers are intrigued by the interactions they glimpse at feeding stations, where juveniles—young of the year that are clearly capable of feeding themselves—nonetheless beg from adults, presumably their parents, who obligingly cough up food for them. This observation suggests that, even after they attain independence, juvenile New Caledonian crows may stay with Mom and Dad, a behavior that strongly suggests a cooperative system.

In general, cooperative breeding occurs when young birds delay dispersal (and thereby forgo the opportunity to mate and produce young of their own) in favor of remaining with their parents and helping out around home. And this eccentric behavior is not restricted to exotic South Sea islands; it can also be observed in backyards and parks in many parts of Canada and the United States. Thanks largely to the Herculean efforts of Caffrey, McGowan, and their co-workers over the past dozen years, we now know that cooperative breeding is common—though not universal—among American crows. Across the northern plains, for example, in a region that includes the Canadian prairies but that has not yet been conclusively mapped, the crows appear to breed as independent pairs, without the assistance of helpers. Elsewhere on the continent, by contrast, although some pairs breed as independents, a significant percentage of broods are attended by retinues of three, six, ten, or even a dozen crows, mostly the grown-up offspring of the breeding pair.

➣

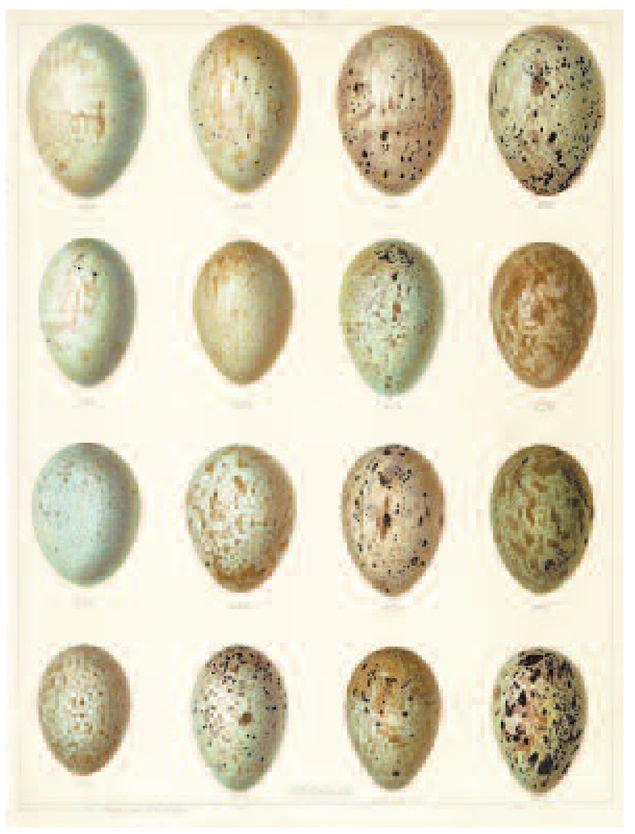

This array includes, from left to right, eggs of the common raven,

Corvus corax;

carrion crow,

C. corone;

hooded crow,

C. cornix;

and rook,

C. frugilegus.

This array includes, from left to right, eggs of the common raven,

Corvus corax;

carrion crow,

C. corone;

hooded crow,

C. cornix;

and rook,

C. frugilegus.

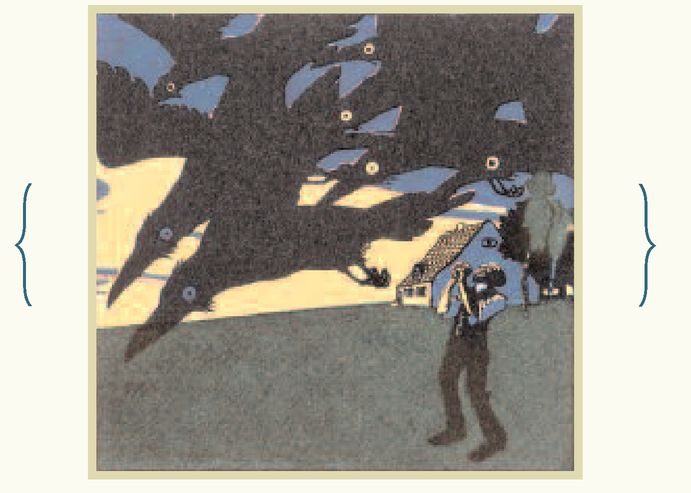

The Seven Ravens,

The Seven Ravens,by A. Weisgerber, 1905.

COUNTING CROWS

OLD ENGLISH RHYME

One crow sorrow,

Two crows joy,

Three for a girl,

Four for a boy,

Five for rich,

Six for poor,

Seven for a witch,

I can tell you no more.

Two crows joy,

Three for a girl,

Four for a boy,

Five for rich,

Six for poor,

Seven for a witch,

I can tell you no more.

Some of these so-called helpers never contribute much and seem to be freeloading off their parents. But others pitch in, whether by standing guard over the family territory, helping to chase intruders away, bringing food to the female on the nest, or feeding nestlings. “I have observed helpers literally following in their parents’ footsteps,” Caffrey reports, “sitting next to and watching their parents during nest building, being thwarted by breeders as they attempted to feed nestlings inappropriate items, and jostling with the breeding female for a chance to brood eggs and nestlings, something she never lets them do.” Perhaps the helpers are parents-in-training, acquiring skills that they will later use in rearing their own broods, though there is as yet no evidence that this speculation is true. Crows that have served as helpers are no more successful in fledging young on their first independent breeding attempt than those that have no prior experience.

LIFE STORIESThe benefits of cooperative breeding, whether for the helpers or their folks, are still a matter of conjecture. And if the whys of the situation are perplexing, the hows—the way in which each individual youngster decides what to do—are even more wonderfully mystifying. Somehow, each young crow in a cooperative population chooses among an open-ended range of options. In any given brood, one individual (likely a female) may disperse permanently to join a family miles down the road and thereafter return at most for an occasional visit. Meanwhile, another may leave for weeks or months and then come back home to live and even to assist its parents. Another (typically a male) may stay put for a year or two or longer, either helping or just hanging out, before eventually moving in with the next-door neighbors and becoming a member of that group.

CROW TEMPERAMENT

A family of young crows roosts “in a row, like the big folks,” in this drawing by Ernest Thompson Seton, 1898.

A family of young crows roosts “in a row, like the big folks,” in this drawing by Ernest Thompson Seton, 1898.FROM “INDIVIDUALITY, TEMPERAMENT AND GENIUS IN ANIMALS,” BY ROBERT M. YERKES AND ADA W. YERKES,

NATURAL HISTORY,

APRIL 1917

NATURAL HISTORY,

APRIL 1917

T

he experimenter who ignores individuality or temperament in his subjects runs a grave risk of misunderstanding or wrongly evaluating his results. Our descriptions sound anthropomorphic, but that, the alert reader will appreciate, is due to our avoidance of stilted and unnatural terminology. We are attempting to describe in an intelligible way, and briefly, behavior which, if we should restrict ourselves to wholly objective terms, would require pages of unusual behavioristic statement.

he experimenter who ignores individuality or temperament in his subjects runs a grave risk of misunderstanding or wrongly evaluating his results. Our descriptions sound anthropomorphic, but that, the alert reader will appreciate, is due to our avoidance of stilted and unnatural terminology. We are attempting to describe in an intelligible way, and briefly, behavior which, if we should restrict ourselves to wholly objective terms, would require pages of unusual behavioristic statement.

Among the birds, there is probably no more interesting object of study than the crow.... One summer we removed a brood of four young crows from their nest just before they were able to fly.... Our space will not permit us to recite in detail, as we are tempted to do, the peculiarities which these birds exhibited during that memorable summer. We must content ourselves with the simple statement that in reactions… of wildness, fear, timidity, curiosity, suspicion, initiative, sociability, the individuals differed most obviously and importantly. We hope sometime, in justice to the problem of crow temperament, to devote a summer to the intensive study of sex and individual differences in these extremely intelligent birds.

Other books

Darkness Unmasked (DA 5) by Keri Arthur

Hotel Kerobokan by Kathryn Bonella

When He Was Bad by Shelly Laurenston, Cynthia Eden

Ghosts of Winters Past by Parker, Christy Graham

Flushed by Sally Felt

River Town by Peter Hessler

To the Hermitage by Malcolm Bradbury

Are You in the House Alone? by Richard Peck

Viking Fire by Andrea R. Cooper

Blackhill Ranch by Katherine May