Crows (3 page)

Authors: Candace Savage

Crows and ravens make a statement just by being themselves. Everything about them says, “It’s me. I’m here. This is my world, my place in the world, and don’t you forget it.” They are the opposite of shyness, the antithesis of camouflage, the very embodiment of self-promotion. And although their showy behavior is primarily intended to attract the attention of others of their kind, their“advertising package” is also ideally pitched to attract the human ear and eye. Unlike the little dickey-birds that set us scrambling for binoculars and frantically twiddling knobs, crows are big and bold, making them easy to observe and identify. As a rule, individual species of

Corvus

are not difficult to tell apart, if you spend a few minutes learning their particular field marks. The common raven, for example, can be distinguished from all the other crows that share its range by its large size; its big schnoz, or heavy bill; its slotted wing tips; and its diamond-shaped, rather than fan-shaped, tail.

Corvus

are not difficult to tell apart, if you spend a few minutes learning their particular field marks. The common raven, for example, can be distinguished from all the other crows that share its range by its large size; its big schnoz, or heavy bill; its slotted wing tips; and its diamond-shaped, rather than fan-shaped, tail.

Even the crows’ harsh voices are—if not exactly music to our ears—surprisingly companionable. Technically speaking, crows are songbirds, though you wouldn’t know it from what comes out of their mouths. Not for them a soaring aria that would put the Three Tenors to shame. Instead, crow

This lovely French illumination, which dates from 1410, shows the sun god Apollo with his white raven. Below, learned people discourse on learned subjects.

This lovely French illumination, which dates from 1410, shows the sun god Apollo with his white raven. Below, learned people discourse on learned subjects.

vocalizations are earthy, studded with what sound to us like consonants and vowels, as if their caws and “quorks” were pronouncements in some unintelligible tongue. And this attunement between humans and crows, this resonance, is both striking and unexpected. Why the connection between bird and mammal? For whatever reason, crows stir our senses, and, over the centuries, their harsh calls have echoed loudly through our dreams and myths. When the legendary Crow or Raven speaks, even the gods listen.

GHASTLY, GRIM, AND ANCIENT RAVEN➣

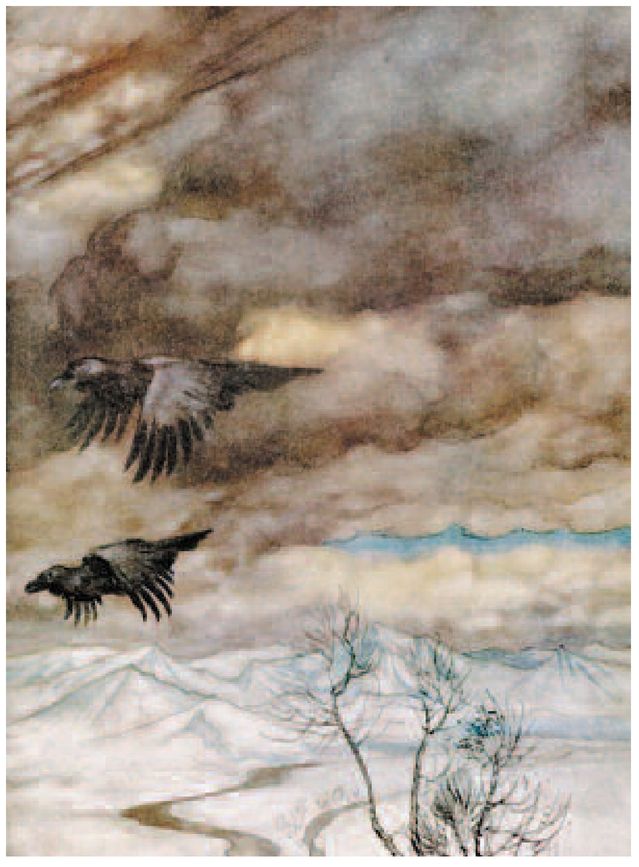

In this illustration by Arthur Rackham, the mythic ravens Hugin and Munin drift over the mountains of Valhalla.

In this illustration by Arthur Rackham, the mythic ravens Hugin and Munin drift over the mountains of Valhalla.

This lovely French illumination, which dates from 1410, shows the sun god Apollo with his white raven. Below, learned people discourse on learned subjects.

This lovely French illumination, which dates from 1410, shows the sun god Apollo with his white raven. Below, learned people discourse on learned subjects.In ancient Greece, the raven was celebrated as the sacred bird of Apollo, god of healing, prophecy, and the sun. But even familiars of the gods can get into trouble. As Ovid tells us in his

Metamorphoses,

it seems that Apollo once had a lover named Coronis, the prettiest girl in all of Thessaly, though not, alas, the most chaste. One day, Apollo’s Raven—at that time a splendid, silver-white bird—caught the girl in

flagrante delicto

and, “merciless informer” that he was, flew straight to his master and shouted out what he had seen. Boiling with Olympian rage, Apollo picked up his bow and arrow and shot Coronis through the breast, then almost immediately succumbed to regret. Unable to save his lover, he turned on Raven instead, the fatal loudmouth that had uttered a truth better left unsaid. As punishment for this lapse of discretion, Apollo banished Raven from the company of white birds, which is why, to this day, ravens are black as night yet bright as the sun’s rays.

Metamorphoses,

it seems that Apollo once had a lover named Coronis, the prettiest girl in all of Thessaly, though not, alas, the most chaste. One day, Apollo’s Raven—at that time a splendid, silver-white bird—caught the girl in

flagrante delicto

and, “merciless informer” that he was, flew straight to his master and shouted out what he had seen. Boiling with Olympian rage, Apollo picked up his bow and arrow and shot Coronis through the breast, then almost immediately succumbed to regret. Unable to save his lover, he turned on Raven instead, the fatal loudmouth that had uttered a truth better left unsaid. As punishment for this lapse of discretion, Apollo banished Raven from the company of white birds, which is why, to this day, ravens are black as night yet bright as the sun’s rays.

In Norse mythology, ravens had the ear of the warlike Odin, the father of the gods. Having traded one of his eyes for a sip at the Well of Wisdom, Odin relied on his black henchmen, the ravens Hugin and Munin, to fly through the nine worlds and return at night to his throne, bringing him whispered news of everything that was going on. Often the news was bloody—Munin means “memory,” especially memory of the dead. And ravens were also associated with the gruesome Valkyries (from Old Norse

valkyrja

and Old English

waelcrige,

the raven, or “chooser of the slain.”) Not only did the ravening corpse goddesses flock to the scene of battle, but they could also see into the future, foretell the outcome of the combat, and determine which of the warriors were doomed to die. The Irish war goddess Badb performed the same bloody services, in the guise of either a raven or a carrion crow.

valkyrja

and Old English

waelcrige,

the raven, or “chooser of the slain.”) Not only did the ravening corpse goddesses flock to the scene of battle, but they could also see into the future, foretell the outcome of the combat, and determine which of the warriors were doomed to die. The Irish war goddess Badb performed the same bloody services, in the guise of either a raven or a carrion crow.

Crows and ravens are scavengers, which is a polite way of saying that they eat the dead, so it is darkly fitting that they were linked to the carnage wrought by swords and war axes. In India, by contrast, the pretty little house crow,

Corvus splendens,

is a bird of the domestic scene, found around virtually every human habitation in the country, even in the center of crowded cities. Perhaps the only species of bird that is entirely dependent on humans for its habitat, the house crow has been living communally with people for hundreds of years, feeding on garbage, nesting in treed gardens, and performing aerial stunts off the tops of tall buildings. But house crows are also found on the burning grounds, where the dead are laid on their funeral pyres for cremation.

Corvus splendens,

is a bird of the domestic scene, found around virtually every human habitation in the country, even in the center of crowded cities. Perhaps the only species of bird that is entirely dependent on humans for its habitat, the house crow has been living communally with people for hundreds of years, feeding on garbage, nesting in treed gardens, and performing aerial stunts off the tops of tall buildings. But house crows are also found on the burning grounds, where the dead are laid on their funeral pyres for cremation.

Common raven, as pictured by Rev. F.O. Morris in his

Common raven, as pictured by Rev. F.O. Morris in hisA History of British Birds,

1851.

DEMON

BIRD

BIRD

D

uring the witch craze in Western Europe, ravens and crows were sometimes feared as demons. In Strathnaver, Scotland, for example, in the seventeenth century, an entire congregation of prayerful souls was seized with dread when they sensed a spectral raven in the house with them. Evil emanated from this shadowy presence, and the people were paralyzed with fear. A day passed and then another, and the group decided to sacrifice the householder’s son to the bird spirit. And so they would have done had it not been for the intervention of a servant. Eventually, neighbors rallied to tear the roof off the house, and the raven’s dire spell was broken.

uring the witch craze in Western Europe, ravens and crows were sometimes feared as demons. In Strathnaver, Scotland, for example, in the seventeenth century, an entire congregation of prayerful souls was seized with dread when they sensed a spectral raven in the house with them. Evil emanated from this shadowy presence, and the people were paralyzed with fear. A day passed and then another, and the group decided to sacrifice the householder’s son to the bird spirit. And so they would have done had it not been for the intervention of a servant. Eventually, neighbors rallied to tear the roof off the house, and the raven’s dire spell was broken.

Mrs. Stene-Tu and her son, members of the Tlingit Raven Clan in southeastern Alaska, were photographed in their potlatch dancing costumes around 1900.

Mrs. Stene-Tu and her son, members of the Tlingit Raven Clan in southeastern Alaska, were photographed in their potlatch dancing costumes around 1900.As an intimate presence in both life and death, the crow is revered in India as an evocation of the ancestors and is respectfully fed both at times of bereavement and during an annual period of remembrance called Shraadh.

What if it is true that the crows hopping around on the boulevard embody the memory of the beloved dead? Or more portentous yet, what if in their dark shining they represent the mystery at the very heart of existence?

In Native communities around the Northern Hemisphere (particularly the northwest coast of North America and eastern Siberia), people cherish the living tradition of a spirit Raven, or sometimes a spirit Crow, which imparted its irreverent and ribald spirit to the world. A rapscallion of the first order, with no regard for decorum or sentiment, this great Raven created humans and then, more or less whimsically, condemned them to death. According to a tradition of the Tlingit people, recorded in writing in Wrangell, Alaska, in 1909, Raven made two attempts to produce humans, once out of rock, a project he abandoned because it was too slow, and once from a leaf, an easy-to-use material that suited him better. “You see this leaf,” he said to his new creations. “You are to be like it. When it falls off the branch and rots, there is nothing left of it.” That is why people die, the elders said, because

Raven had made them from leaves that perish. According to the Australian Aborigines, by comparison, the great Crow created death because he wanted to have his fun with the widowed women.

Raven had made them from leaves that perish. According to the Australian Aborigines, by comparison, the great Crow created death because he wanted to have his fun with the widowed women.

Other books

Tainted Love: A Lovestruck Novella, Book 1 by Lane Hart, Aaron Daniels, Editor's Choice Publishing

The Pastor’s Jezebel Lover by Nic Saint

Sons by Pearl S. Buck

Ascending the Boneyard by C. G. Watson

The Dead of Winter by Chris Priestley

Love Me an Angel: A Biker Erotic Romance by Hampton, Sophia

Rebecca's Return by Eicher, Jerry S.

Dirty Deeds (Paranormal Erotic Romance) by Gayle, Eliza

A Matter of Choice by Laura Landon

The Last Tsar: Emperor Michael II by Donald Crawford