Crows (14 page)

Authors: Candace Savage

The only possible conclusion was that, with the probable exception of a few basic vocalizations like the begging cry of nestlings and the yell of feeding mobs, ravens’ calls do not come with genetically preassigned functions. Instead, it seems that these clangorous utterances acquire their definition and meaning in the context of each raven’s social experience. Although “ravenese” may not be a symbolic language as we know it, neither is it a simple system of signals, a collection of bestial grunts and groans. We’re beginning to catch a glimpse of something beautiful.

CROW EMOTIONIf only, just for a day, we could get inside the skin of a crow or a raven. Imagine: settling your mantle of rustling black feathers, taking flight, floating on languorous wings through the thin air. What would that crow-self see or think or remember? How would its harsh voice reverberate on its own ear? And most mysterious of all, how would it feel? If William Shakespeare was right to suggest that “one touch of nature makes the whole world kin,” does that kinship extend to the blustery inner landscape of emotion?

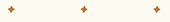

THE SEVEN RAVENS

Feast of the Seven Ravens,

Feast of the Seven Ravens,by Arthur Rackham, 1900.

PARAPHRASED FROM

CHILDREN’S AND HOUSEHOLD TALES

BY JACOB AND WILHELM GRIMM, 1812

CHILDREN’S AND HOUSEHOLD TALES

BY JACOB AND WILHELM GRIMM, 1812

T

here was once a man who had seven sons and a much-loved but sickly daughter. Fearing she would die, he sent the sons to get water from the well so that the girl could be baptized. In their eagerness to fulfill his wishes, the boys jostled with one another, and the jug disappeared down the well. They did not know what to do. When his sons failed to return home as expected, the father flew into a temper and said: “I wish the boys were all turned into ravens.” Hardly had he spoken when he heard a whirring of wings and looked up to see seven coal-black ravens flying away.

here was once a man who had seven sons and a much-loved but sickly daughter. Fearing she would die, he sent the sons to get water from the well so that the girl could be baptized. In their eagerness to fulfill his wishes, the boys jostled with one another, and the jug disappeared down the well. They did not know what to do. When his sons failed to return home as expected, the father flew into a temper and said: “I wish the boys were all turned into ravens.” Hardly had he spoken when he heard a whirring of wings and looked up to see seven coal-black ravens flying away.

The parents were sad at the loss of their sons but were consoled by the health of their little daughter, who soon grew strong and ever more beautiful. At first, she did not know about her brothers, but eventually she overheard someone talking about what had happened. And so it was that she set out to rescue them.

Her journey took her through many trials and terrors, including journeys to the sun and moon. Eventually, the morning star gave her a chicken drumstick, which would open the door of a Glass Mountain, where her brothers were held. Alas, by the time she got there, the drumstick had been lost, and she was forced to cut off her little finger and use it to open the lock.

Once inside the mountain, she had to wait for her brothers, the seven lord ravens, to return for their evening meal. Suddenly she heard a stirring of wings and a rushing through the air, and the great black birds appeared. Her loving presence was enough to break the curse and restore the ravens to their human form, and amid much rejoicing, the family returned home.

CROWS

Young Marion Gaynor feeds her pet crow, “Pete,” early 1900s.

Young Marion Gaynor feeds her pet crow, “Pete,” early 1900s.It’s hard enough to understand the things that birds and animals do—how they interact, make decisions, and communicate with one another. But the vaporous stuff of feeling almost defies investigation. To date, scientists have been able to demonstrate that crows and ravens express a range of “motivational intensities,” from uninterested to maximum arousal. There is, for instance, a graphable relationship between the number of hunger cries emitted by baby crows and the number of minutes that has elapsed since their parents last brought food. The same is true of territorial invasions; the more serious or the more prolonged the threat, the louder and more frantic the vocalizations.

But although these statistics tell us that the birds are probably feeling something, they cannot tell us what those feelings are. Here our best and only guide is intuition. In his 1989 book

Ravens in Winter,

Bernd Heinrich reflects on the unexpected emotional rapport he often senses with his black-winged research subjects.“It surprises me,” he writes,“that many of the ravens’ calls… display emotions that I, as a mammal for whom they are not intended, can feel.” When two ravens are tucked up intimately together, they make cooing sounds that sound tender to his ear. When they are in a situation that would

make him angry, their deep, rasping complaints seem to express anger. In addition, Heinrich believes that he can sense a wide range of other emotions from a raven’s voice and body language, including surprise, happiness, distress, bravado, and braggadocio. “Emotions are more ‘primitive’ than reason,” Heinrich notes, “and I presume that many animals have very similar emotions to our own.” But the emotional symmetry between corvids and humans is something special.

Ravens in Winter,

Bernd Heinrich reflects on the unexpected emotional rapport he often senses with his black-winged research subjects.“It surprises me,” he writes,“that many of the ravens’ calls… display emotions that I, as a mammal for whom they are not intended, can feel.” When two ravens are tucked up intimately together, they make cooing sounds that sound tender to his ear. When they are in a situation that would

make him angry, their deep, rasping complaints seem to express anger. In addition, Heinrich believes that he can sense a wide range of other emotions from a raven’s voice and body language, including surprise, happiness, distress, bravado, and braggadocio. “Emotions are more ‘primitive’ than reason,” Heinrich notes, “and I presume that many animals have very similar emotions to our own.” But the emotional symmetry between corvids and humans is something special.

Kevin McGowan, the crow man of Ithaca, New York, has no doubt that the birds in his studies have feelings, some of which are directed at him. Many of the crows in the city hate him. In particular, he remembers a young male helper crow that he banded on the campus of Cornell University, in a territory that was used by thousands of people every day. The crow would watch the crowds come and go without fury or fuss, but when McGowan showed up under the nest with his binoculars once every three or four months, the crow would raise a ruckus.“He would pick me out from all those people and start yelling and following me around.” Thinking that maybe the binoculars were the giveaway, McGowan suited up a friend and sent him out instead, but the crow completely ignored him.

When his study was most active, McGowan gained such a bad “rep” that he couldn’t go anywhere in the city without arousing a storm of resentment. “Everybody would join in,” he recalls. “I’ve had as many as seventy-five crows after me at once.” As he extended his research onto territories he had never visited, he discovered that the local crows had often been forewarned. “Some of these guys knew me—they’d start to object the minute I showed up—even though I had never knowingly met them.” In the end, he got so tired of playing the bad guy that he started to throw peanuts to the crows he met, “in the hope of making a few friends.”

➣

The harsh calls of a northwestern crow rip through the bright air.

The harsh calls of a northwestern crow rip through the bright air.

EMOTIONS aremore

“PRIMITIVE”

than REASON, and I presume

that many

animals

have very

similar emotions to our

OWN.

BERND HEINRICH

“PRIMITIVE”

than REASON, and I presume

that many

animals

have very

similar emotions to our

OWN.

BERND HEINRICH

Other books

The Wizard of Lies: Bernie Madoff and the Death of Trust by Diana B. Henriques, Pam Ward

Her Fantasy Husband (Things to Do Before You Die) by Nina Croft

Her Accidental Boyfriend: A Secret Wishes Novel (Entangled Bliss) by Bielman, Robin

A Private Sorcery by Lisa Gornick

Werewolf: A World at War Novel (World at War Online Book 4) by Mitchell T. Jacobs

Private Relations by J.M. Hall

Celebrity Shopper by Carmen Reid

Ask the Right Question by Michael Z. Lewin

Affairs of Art by Lise Bissonnette

The Red Witch (Amber Lee Mysteries Book 6) by Katerina Martinez