Crows (13 page)

Authors: Candace Savage

In this illustration from

In this illustration fromThe Lilac Fairy Book,

1919, the youngest of three sisters agrees to marry a sweet-talking hooded crow.

Singing has a calming effect on crow interactions, Brown notes. When two family members come into conflict, one of them often begins to sing, instantaneously putting an end to the hostilities. The more song elements any given pair has in common, the more companionable the birds tend to be and the more time they spend socializing and preening one another’s plumage. And the reverse also holds true: The fewer shared sounds, the weaker the social link. For instance, when a lovey-dovey pair of sisters was placed in an aviary with an unrelated crow that had a different song, the established two-some completely ignored the stranger. But as soon as the outsider learned to replicate the sisters’ distinctive coo calls, they acknowledged her as one of the group and accepted her as a preening partner. To paraphrase the old saying, it seems that crows of a song join the same throng.

THE CULTURE OF RAVENSGiven what we know about crows, it is not surprising to learn that their vocal behavior is intensely social. But what if someone were to tell you about a species in which social partners not only learn calls from one another but also somehow agree on how to use those calls meaningfully? This is the picture that has been emerging over the last twenty-odd years from a study of common ravens conducted by zoologists Peter Enggist and Ueli Pfister, in an area just south of Bern, Switzerland. The research protocol is simple. A cage containing two captive ravens is placed inside the territory of a wild, free-living pair, and the sounds the birds make during the encounter are recorded. Back in the lab, the biologists analyze the recording, tally the number of “call types” used by each bird—a wonderful variety of gurgling, chortling, trilling, knocking, barking, “quorking,” and bell-like peals—and then compare the repertoire of these new subjects with the sounds that are already on record.

To date, the researchers have compiled a library of more than 64,000 vocalizations, elicited from 37 raven pairs. From this cacophony, they have distinguished 84 distinctly different calls, and the list continues to grow as each new pair of ravens is added to the choir. Within the limits of their syringeal organs, the birds appear to be free to learn, imitate, and invent, and their collective vocal repertoire is thought to be open-ended. Yet with all these possibilities at their disposal, each individual adult raven has a limited vocabulary of only about a dozen calls. A few of these creakings and groanings are unique to particular individuals, but most are shared with at least a few other members of the broader population. Could it be that ravens learn some of these vocalizations from one another during adolescence, when they hang out together as roost mates and meet in feeding mobs? Suggestively, the calls of juvenile ravens are more diverse and variable than those of adults.

➣

Crows and ravens share an intense social awareness.

Crows and ravens share an intense social awareness.

HANSL

the talking

CROW

the talking

CROW

Poster for a film version of Poe’s “The Raven,” about 1908.

Poster for a film version of Poe’s “The Raven,” about 1908.FROM

KING SOLOMON’S RING: NEW LIGHT ON ANIMAL WAYS,

BY KONRAD Z. LORENZ, 1952

KING SOLOMON’S RING: NEW LIGHT ON ANIMAL WAYS,

BY KONRAD Z. LORENZ, 1952

“

H

ansl,”

[a carrion crow that lived in the Austrian village of Worden]

could compete in speaking talent with the most gifted parrot. The crow had been reared by a railwayman in the next village, and it flew about freely and had grown into a well-proportioned, healthy fellow, a good advertisement for the rearing ability of its foster-father… [By taking care of him once at his owner’s request,] I found out that Hansl had a surprising gift of the gab and he gave me the opportunity of hearing plenty! He had, of course, picked up just what you would expect a tame crow to hear that sits on a tree, in the village street, and listens to the “language” of the inhabitants…

H

ansl,”

[a carrion crow that lived in the Austrian village of Worden]

could compete in speaking talent with the most gifted parrot. The crow had been reared by a railwayman in the next village, and it flew about freely and had grown into a well-proportioned, healthy fellow, a good advertisement for the rearing ability of its foster-father… [By taking care of him once at his owner’s request,] I found out that Hansl had a surprising gift of the gab and he gave me the opportunity of hearing plenty! He had, of course, picked up just what you would expect a tame crow to hear that sits on a tree, in the village street, and listens to the “language” of the inhabitants…

Once he was missing for several weeks and, when he returned, I noticed that he had, on one foot, a broken digit which had healed crooked. And this is the whole point of the history of Hansl, the hooded crow. For we know just how he came by this little defect. And from whom do we know it? Believe it or not, Hansl told us himself! When he suddenly reappeared, after his long absence, he knew a new sentence. With the accent of a true street urchin, he said, in lower Austrian dialect, a short sentence which, translated into broad Lancashire, would sound like “Got ’im in t’bloomin’ trap!” There was no doubt about the truth of this statement… How he got away again Hansl unfortunately did not tell us.

Although no one knows how young ravens acquire their calls, it is clear that the adults can learn new vocalizations from one another. During the Swiss study, for example, one of the captive males picked up three new utterances from a wild male that he visited. In general, it seems that ravens acquire many of their calls from other members of their sex and that some sounds are almost exclusively gender-specific. As a result, male and female repertoires tend to be quite different from one another. These differences are, however, minimized to a certain extent between mates, which often share four or five calls, some of which they probably learn from one another.

And that’s when things really get interesting. For not only do the members of each pair have a distinctive vocal repertoire, but they also have their own rules about how the sounds in their collective vocabulary are to be used. For instance, when presented with the cage of captive ravens, one wild female in the Swiss study responded to the intrusion with a short, rasping quack, which her partner typically answered with a guttural honking call. In another pair, by contrast, the female reacted with the same quacking call, but her

mate replied with a liquid “kwa,” a sound that no other raven in the study was heard to utter. His honking call, by contrast, was used in response to one of his partner’s other calls—a dactylic triplet (long-short-short) of harsh, rasping barks. And so it went, through countless permutations. Although the situation was always the same—a cage of ravens dropped off in the woods—each pair’s response was unique.

mate replied with a liquid “kwa,” a sound that no other raven in the study was heard to utter. His honking call, by contrast, was used in response to one of his partner’s other calls—a dactylic triplet (long-short-short) of harsh, rasping barks. And so it went, through countless permutations. Although the situation was always the same—a cage of ravens dropped off in the woods—each pair’s response was unique.

➣

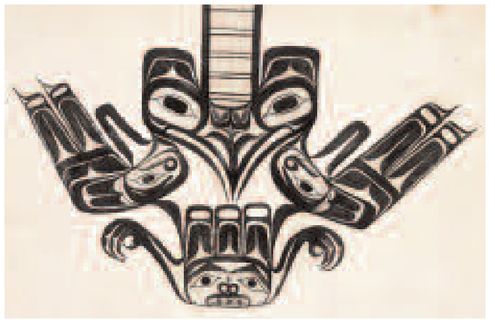

This image of “Hooyeh,” the heraldic raven of the Haida people of the Queen Charlotte Islands, was created by Johnny Kit Elswa in 1883.

This image of “Hooyeh,” the heraldic raven of the Haida people of the Queen Charlotte Islands, was created by Johnny Kit Elswa in 1883.

Other books

Graven Images by Paul Fleischman

A Life Transparent by Todd Keisling

Enchanting World of Garden Irene McGeeny by Kennedy, Concetta

Blackhill Ranch by Katherine May

Carnal Captive by Vonna Harper

Philip and the Sneaky Trashmen (9781619502185) by Paulits, John

A Tale for the Time Being by Ruth Ozeki

Chosen By The Prince by Calyope Adams

Darkfall by Dean Koontz