Crossing the Borders of Time (12 page)

Elisabeth “Lisette” Hauser Cahen in 1932 with her twin daughters

Even as Alice fretted over Lisette’s freethinking influence upon Janine, and regretted Norbert’s stunted schooling, and worried about their lack of income, and hated Sigmar’s weary travels, and missed her home and extended family, there was no bemoaning leaving Freiburg. Grisly reports from across the border proved they had fled not a moment too soon. Already, thousands of German Jews had been deported to camps—their locations and nature largely unknown—and Hitler’s reach was expanding.

When, at the end of October 1938, the Nazis expelled eighteen thousand Polish-born Jews from Germany, sending them off by train with neither possessions nor money, the enraged son of one such uprooted Jew fatally shot a minor official at the German embassy in Paris. Violent reprisals on November 9 and 10 unleashed unprecedented terror and destruction throughout Germany, including Freiburg. Storm troopers torched more than one thousand synagogues, feeding bonfires with holy texts, scrolls of the Torah, and ritual objects. Joined by unrestrained mobs, they smashed windows of tens of thousands of Jewish shops and homes; they attacked and murdered Jews on the streets and filled concentration camps with about thirty-five thousand others, roughly 10 percent of the Jews still left in the country. In what was dubbed

Kristallnacht

, crystal night—a lyrical name for a pogrom—the Nazis shattered not only glass, but also any illusion that the Reich would uphold moral justice. In Freiburg, historically esteemed as a bastion of scholarship and culture, the grand nineteenth-century synagogue was burned to the ground.

Seized in the roundup was Sigmar’s brother Heinrich. According to a certificate of incarceration later issued to him by the International Red Cross, Heinrich Günzburger, prisoner number 21973, then sixty years old, had been arrested on grounds of being a Jew. As with most of the ten thousand Jewish men imprisoned at Dachau in the wake of

Kristallnacht

, his release a month later came with a warning to get out of the country. The goal of purging Jews from German-held lands thus began with forced emigration, and Heinrich wasted no time in fleeing to Mulhouse. He hoped from there to reunite in Geneva with his wife, Toni, and prayed that having sent their two sons to Buffalo, New York, a few years earlier, they, too, would soon qualify for American visas.

On the day that Heinrich arrived in Mulhouse, Sigmar met him at the train station and encountered a broken man, horribly burned, trembling, and near catatonic. His red eyes stared blankly back into themselves, and tears rolled down his gaunt gray cheeks. One arm was a long, garish wound from elbow to wrist, the skin charred and oozing, split raw and open down to the bone. In the jammed barracks at Dachau, Heinrich had been wedged against a fiery wood-burning stove when a Nazi officer commanded the inmates to stand at attention for hours. The first man to speak or move a muscle, the officer barked, would be shot on the spot. So Heinrich stood rigid, his nausea at the stench and pain of his own burning flesh only checked by his harrowing fear.

It fell to Alice to clean the burned arm and change his bandages several times daily, a gruesome reminder of her bloodstained World War I service, when she’d nursed that same generation of Germany’s soldiers. Within days, when a telephone call came from the wife of her cousin in Frankfurt, Alice collapsed. On the night of the madness, the woman reported, storm troopers had crashed through their door and ransacked their home. When her husband, the director of a Frankfurt opera company, demanded an explanation from them, the intruders answered by beating him up and then dragged him away. Two days later, one of the men returned to shove a small cardboard box into her hands. It held ashes—all that remained of her husband, who was shot in the back attempting escape. Or so she was told. “See, he’s home again,” the unidentified messenger spat out the words. “Didn’t I promise we’d bring him back to you soon?”

From Zurich came better news that Alice’s mother Johanna and the rest of the family—Alice’s sister Rosie, her brother-in-law Natan Marx, and her niece Hannchen—had managed to get out of Eppingen before

Kristallnacht

, albeit penniless. Weeks earlier, two members of the brutal Nazi paramilitary force called the

Schutzstaffel

, or SS, had barged into the Heinsheimer store; they took Natan’s volunteer fireman’s helmet, confiscated the family’s passports, and examined the business’s records. Then the SS demanded the sale of the store, their house, and their land and required them to turn over the proceeds as taxes in exchange for their passports. After eight generations in the same modest village, the family was ordered to clear out, but was left with so little they needed a loan from a cousin in Holland to secure transportation. Johanna took refuge with another daughter in Zurich, while the Marxes—having applied for visas years before Sigmar acknowledged the need—escaped from Europe on a ship to New York.

Two days after

Kristallnacht

, German Jewry was collectively fined one billion Reichsmarks for the destruction leveled against it, a punishment to be paid through the confiscation of 20 percent of the property of every Jew, including many who already had left. In Sigmar’s case, notice of the new fines arrived in Mulhouse, a chain of documents informing him of sums withdrawn by the Nazi government from the bank accounts he had been forced to abandon. The same Germanic compulsion for order that led the Nazis to keep meticulous records, thorough accounts of money and corpses, dutifully prompted Sigmar to register as required with city officials wherever he landed. As a result, the Freiburg authorities knew just where to find him. Every few months they notified him of thousands of additional Reichsmarks in taxes they had deducted from his blocked bank accounts, on top of the many thousands he’d paid before leaving Freiburg. In a form letter he received in Mulhouse that January, the Nazi authorities threatened that if they had any difficulty in collecting the extra taxes, he would first be charged interest; after that, they would send agents to find him, and he would be forced to reimburse the Reich for their efforts, as well.

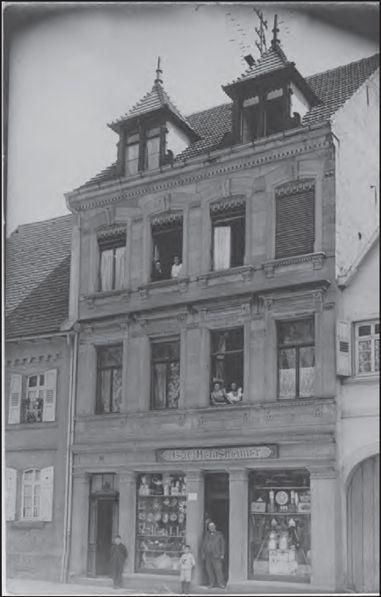

The Heinsheimer family store on the Brettener Strasse in Eppingen with Maier and Siegfried in the doorway and Alice on the left in the window above them

In addition to claims paid to Freiburg’s finance department, Sigmar received notice of heavy taxes withdrawn from his seized accounts to pay Eppingen: Alice’s birthplace had targeted her for inclusion in the fines imposed on its Jewish community for the

Kristallnacht

destruction of the synagogue there. He was also informed that the Reich would be confiscating the equivalent of 20,000 French francs in exchange for its generously “permitting” him to do business in Mulhouse. According to the Nazi regime, although it operated under a different name (

Mesanita

) in a foreign country, any business he ran in France should properly be considered an offshoot of the former Günzburger Brothers’ firm, now in the hands of Aryan owners.

That April, Sigmar wrote to the Freiburg finance authorities outlining arguments seeking reductions. Could the flight tax be deducted from the Jewish wealth tax? Sigmar inquired into the truth of that rumor. A curt reply arrived two days later. “

Ein Abzug der Reichsfluchtsteuer an der Judensvermögensabgabe ist nicht zulässig

.” A deduction of the flight tax from the Jewish wealth tax is not permitted. Conversely, the city added with contorted logic, the Jewish wealth tax

might

have been deducted from the flight tax had Sigmar

not

fled, if he had remained a resident of Germany until after

Kristallnacht

. But because he had emigrated before January 1, 1939, all taxes would remain unabated. In closing, the letter directed that in case he had further questions, he needed to send return postage if he expected an answer.

There was nothing for Sigmar to do but file all these papers in the worn leather briefcase where I found them so many years later. Brown by now and frayed at the edges, many of the documents bear the stamp of the

Finanzamt

with the Nazi insignia of an eagle spreading its wings astride a globe whose center is filled with the swastika’s twisted black cross. They reveal how the finance department changed his name in accord with new regulations—to

Samuel Israel

Günzburger—to show he was Jewish, while withdrawing so many extra “tax” payments from his accounts even after he fled to Mulhouse that the funds on deposit were entirely depleted.

In my grandfather’s many replies, I would see signs of the person whose unwavering faith in the difference between right and wrong guided his every transaction. Even in New York at age eighty, he would walk several blocks back to a supermarket on Broadway to return an extra nickel of change, lest the cashier have to pay for the error out of her pocket. In his polished black wingtips, herringbone topcoat, and soft gray fedora, he would slowly make his way back to the store with the deliberateness of a business mogul concluding a matter worth millions. A man who would later rouse himself on his deathbed to remind his grief-stricken wife to pay the rent and the rest of her bills on the first of each month, he never altered the standards he set for himself. Until

Kristallnacht

, Sigmar had fully believed in the ultimate restoration of justice in the land of his birth, but now optimism gave way to despair.

Still, Sigmar kept his fears to himself so as not to alarm his traumatized brother about their additional losses in Freiburg or, much worse, about what he now understood to be Hitler’s goal to eliminate German Jewry entirely. Heinrich spent all his days in a chair, staring out a large picture window, totally silent, his eyes fixed on the clock in the parc Salvator behind the apartment. The clock’s face, a circle of color embedded in grass, was made entirely of flowers that were changed with the season. Its hands kissed the fading petals of time as the hours and days passed, the weeks and the months, bringing the world ever closer to war, just twenty years after the last one had ended.

But Janine did not seem to notice. Much as the plants in the clock lived by their own biological time, unperturbed by the mechanized sweep of the arms that measured their days, so did she—unaffected as yet by the ticking time bomb just over the border—continue to bloom in her own youthful rhythm. Her attention as a teenager was focused on her circle of friends and on a single, special new interest. Having heard Yvette read Roland’s letters aloud all that fall and having seen him in person at Christmas, she was, above all, eager to meet him. Love, like “the light of the heart,” as Balzac described its effect on a provincial young girl, kindled a fresh sense of wonder. The memories are hers.

One spring afternoon in 1939, as Janine and Yvette strolled after school on the rue du Sauvage, they spotted a group of young men on the corner. “

Regarde! C’est lui! Roland! Il est rentré

,” Yvette whispered to Janine, indicating the tallest among them. Roland had returned. As the two girls approached, he noticed and stiffened, shifting uneasily from foot to foot as he rested lightly on a long, furled umbrella, in the style that British prime minister Neville Chamberlain had made chic for the moment. Unaware that Roland had bitterly learned of her sharing and mocking his letters with friends, Yvette chattered gaily, coquettish, oblivious of his tepid response. But as the two talked, Janine indulged in studying him, as if some glorious mythological being had suddenly alighted to earth in her path. His slim face had high cheekbones and a sensitive mouth, and his velvet brown eyes shone with gentleness. She blushed when he turned and caught her staring at him, like the maiden Psyche stealing forbidden glimpses of the sleeping Cupid, her lover, by candlelight.