Crossing the Borders of Time (7 page)

The Freiburg Synagogue was consecrated in 1885 and destroyed by the Nazis in 1938

.

(photo credit 3.3)

At the Rosh Hashanah holiday marking the Jewish New Year, for instance, the Günzburger children were expected to write to their parents and critique their own past behavior. With their best handwriting in flowery letters that they placed like offerings on their parents’ pillows, they annually extended their thanks and pledged to mend their performance at home and in school. The tone of their letters hardly varied at all:

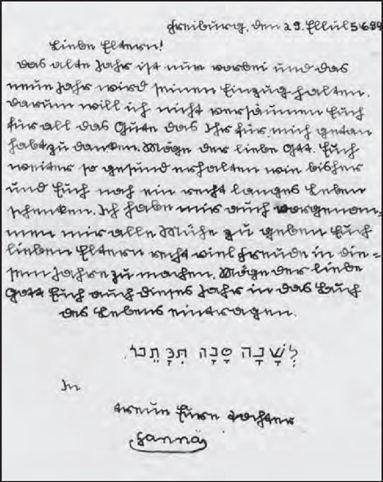

Hanna’s 1934 New Year’s letter to her parents, written in the hard-to-decipher script called

Sütterlin,

taught in German schools from 1915 to 1941

“

I promise to work harder to please you in the New Year

,” Hanna wrote, for example, at age eleven in 1934. “

I won’t give any fresh answers. I will try hard to excel in school

.” And at Rosh Hashanah when she was twelve: “

In the last year, I was sometimes bad. For that I ask you from the bottom of my heart to forgive me. May God make me do only good things and give you all the love and good luck you deserve. So wishes your faithful daughter

.”

In an effort to gain her father’s respect, Hanna worked to find biblical questions she might raise with him during the family’s outings each Sunday, when Buhler, the chauffeur, often drove them to the so-called

Alter Friedhof

or seventeenth-century Old Cemetery, where the ancestors of the town’s Catholic elite lay buried. There—his preferred weekend pastime—Sigmar led them on tours through the elaborate graves, expounding upon the generational histories of the entrenched Freiburg families whose mossy tombstones he found so intriguing.

But whenever Hanna asked him about God or death or the reason for evil, Sigmar’s answer was curt and unyielding. “We don’t question these things,” he sternly rebuked her. Ever after, she cringed to recall how shocked he had been when she tried to show off her biblical insight by sharing the news she had heard from a friend—that Adam and Eve were really chased out of Eden

not

for chastely eating a forbidden apple, but for angering God by engaging in sex with each other. “Who told you such a thing?” Sigmar demanded, and he directed her never to speak with her theological expert again.

Ever aiming to please, in school Hanna was a hardworking and excellent student. Her prize-winning entry in a penmanship contest requiring the use of a highly formal, complicated Germanic script called

Sütterlin

was hung on display in a local museum, and she set her sights on winning the top academic prize in her class, for which Sigmar had held out the reward of a new bicycle. When her marks won top ranking, however, school officials refused to grant her the prize because she was Jewish, and Sigmar made no allowance for that injustice.

As a result, she never got the new bike she craved until she bought

me

a shiny white Schwinn when I was eleven, outfitting it with near-giddy delight with baskets and bell and red handlebar streamers. Then thirty-six, she occasionally rode it around town while I was in school. Yet those solitary excursions up and down the empty hills of suburban New Jersey could not have brought the same joy she had tasted in daydreams, pedaling in all gleaming splendor through the bustling streets of the center of Freiburg, until she arrived at her school, greeted by the admiring glances of all her classmates.

With new laws on education in 1933, the Reich decreed that the proportion of non-Aryan students in German schools should be reduced to a maximum of 5 percent, ousting thousands of Jewish children from their classrooms and forcing them into ad hoc Jewish schools. The Central Committee of German Jews set rules for these schools that called for teaching the children about both sides of their lives, the Jewish and German, about the contributions each had made to the other, and about the tensions dividing them now. Under grave existing circumstances, “the entire education must be directed toward the creation of determined and secure Jewish personalities,” the committee said, because “the Jewish child must be enabled to take up and master the exceptionally difficult struggle for survival which awaits him.” In light of her top academic performance, Hanna was allowed to remain, a token Jew, in the German

Höhere Mädchenschule

(the Higher Girls’ School).

“Now here is the perfect example of a young lady with distinctively Aryan features,” a Nazi Party official observed to her class, his hand on Hanna’s shoulder, during a visit to lecture the students on how to recognize non-Aryan facial characteristics. No one dared contradict him, but the incident inspired Hanna’s teacher to get even with her for “passing” as German. When Christmastime came and the class was preparing its annual play, he assigned her the role of the

Christkind

, the Christ child, whose part called for bearing a sack with a gift for the class. Hanna entered the room with the bag slung over her shoulder, and her classmates rushed from their seats to circle around her, eager to see what Baby Jesus had brought them. But when they tore open the wrapping, she was ashamed to discover the present the teacher selected was a large framed picture of Adolf Hitler. The only Jew in the class, Hanna flushed in humiliation to have been forced to deliver, as if a sacred gift, the Führer’s picture to hang in the schoolroom, and she wept as her classmates hooted with laughter.

Generally speaking, her fellow students nevertheless treated her kindly, even as fear of Nazi reprisals against their parents compelled some of them to ask her to sneak around to their back doors whenever she came to play at their homes. In school, each time a teacher entered a classroom, Hanna had no choice but to join with her classmates, jumping to their feet and shouting “

Heil Hitler!

” with a Nazi salute, until it became such a habit for her that she accidentally greeted the rabbi that way when she encountered him walking alone on the street.

At Monday morning flag-raising ceremonies in front of her school, Hanna’s classmates all wore the Bund Deutscher Mädel (League of German Girls) uniforms that Hitler Youth leaders prescribed for girls: navy skirts with white blouses, white kneesocks with tassels, and wide leather belts and bandoliers. In an effort to blend in, Hanna persuaded Alice to buy a white blouse and socks for her and to have the dressmaker produce a similar kick-pleated skirt. The bandolier, the most desirable part of the outfit, was, of course, not accessible to her. But walking home to the Poststrasse one day after school, she was drawn to a crowd of cheering young people who stood gathered near the train station in front of the Zähringer Hof, one of the city’s finest hotels. Garlands of flowers draped the doorway, and bloodred Nazi banners flew from the windows. The children were shouting and waving to a room several floors high above, calling for “dear Göring,” Hitler’s chief aide, “to be so kind as to come to the window.”

Freiburg’s Adolf-Hitler-Strasse, lined with Nazi banners and flags, between 1935 and 1940. To create a street grand enough to honor the Führer, the city’s main thoroughfare, the Kaiserstrasse, was linked to other streets to the north and south

.

(photo credit 3.4)

Lieber Göring, sei so nett

,

Komm doch mal ans Fensterbrett!

Over and over they chanted their couplet, their clear children’s voices insistent and charged with excitement, until the uniformed figure of Hermann Göring appeared at the window and acknowledged their adulation with an exemplary Nazi salute. Below him stood a generation determined to rise, phoenixlike, from the devastating defeats their parents had suffered in war and under its onerous treaty. But in the cheering crowd on the street, there was at least one young Jewish girl, confused and uncertain, whose voice mingled with those of her German peers.

Many years later, when I was a teenager, my father would bring my mother to tears of frustration and anger at the dinner table when he rebuked her for the passive compliance of Jews who had, out of fear, complied with Fascist commands instead of rebelling.

“What would you have had me do? I was a child. What could any of us do?” she would stammer, her eyes brimming, on the many occasions this issue arose. She never cried out of sadness, but only to drain unvented anger, accumulated over a lifetime and squelched into silence. It was one of the common disputes that sparked my increasingly protective feelings for her, as my father persisted in maintaining that Jews themselves handed power to Hitler through docile acceptance of their own annihilation. He would raise his fist, slide his jaw forward, narrow his eyes, and snarl through clenched teeth, “I might have gone down, but

I

would have taken a bunch of Krauts with me.”

That summer, as usual, the children left to spend their vacation with their grandmother Johanna in Eppingen, a trip always made special by Alice’s having friends and relations greet their train at numerous stops on the way, bringing them treats. “

I can’t believe how many people we have met, and everybody gives us something

,” Hanna enthused in a letter home, describing their journey. “

We couldn’t close the suitcase anymore, we had so many chocolates and goodies!

” A day or so later, they reported their shock to discover a new sign on the gate of the Eppingen pool, which led Alice to threaten to summon them back:

JUDEN UND HUNDE VERBOTEN

, Jews and Dogs Not Permitted. Undeterred, Hanna wrote Alice, begging to stay:

Even though we can’t go swimming anymore, there is still more to do here on vacation than in Freiburg. We tease the geese and play with the horses and chickens. Today we spent in the garden watering the plants. We wore nothing but our undershirts, panties, and aprons. We were barefoot. That’s how we hopped around the whole day. We plucked all the plums from the tree and stuffed them into our underpants. Don’t worry, Trudi has no freckles yet, but you have to send us a new tube of bleaching cream because she will soon run out.…

Listen to this, Mother. Yesterday, a man was here who told us that you, Mother, were a terrible flirt! Don’t you say anything more to

us

! (Excuse the grease spot on this letter. It came from a pickle sandwich I am eating just now.) You, dear Mother, are a world-known lady here. Everybody one meets knows the Lisel.

Hanna (L) and Trudi picking daisies on summer holidays in Eppingen

When the children returned to Freiburg in September, Sigmar and Alice had not forgotten the notice posted at the Eppingen pool. Channeling their need to belong—if not in the larger community of the town, then with their peers—Sigmar enrolled all three in the Bund Deutschjüdischer Jugend (League of German Jewish Youth), one of two Jewish recreational clubs. The other youth group had a Zionist outlook and a more daring agenda, but still adamant in his sense of himself as a true German, Sigmar ruled out his children’s joining a movement whose stated goal involved emigration.