Crossing the Borders of Time (4 page)

Two generations later, while arranged marriages between suitable Jewish families remained the norm, the union of Simon and Jeanette was a rare love match, according to family legend. A large man with laughing eyes, full cheeks, and a thick curly beard, Simon made his living as a cattle dealer, a common trade for Jews in Germany’s southwestern region. It was lonely work requiring much travel, and Simon roamed the countryside with a goal of getting home each week in time for the Sabbath. It would later be said that his amorous wife—in whose memory Hanna’s parents had sought to name her Jeanette—spent his absences immersed in romantic novels and greeted him passionately on his returns, accounting for their numerous offspring. Perhaps it was the influence of fiction that inspired the exotic, non-Hebrew names Jeanette gave many of her children (among them Heinrich, Karoline, Hermann, Norbert, Marie, and Adolf), raising eyebrows of Jewish neighbors. As for my grandfather, while officially named Samuel, he was invariably known by his Germanic middle name of Sigmar, likely because at the time of his birth in 1880, festering anti-Semitism was swelling again.

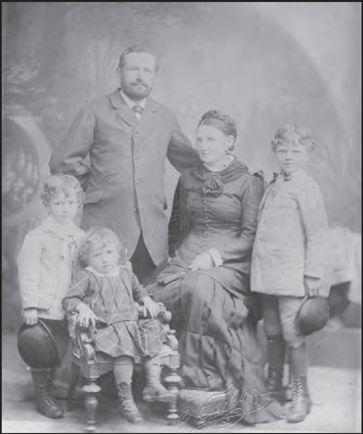

Simon and Jeanette Günzburger with their three youngest sons, Heinrich (L), Sigmar (seated), and Hermann, circa 1882

(photo credit 2.3)

This was especially the case in agricultural regions such as Ihringen, where Jews worked as middlemen handling trade and became targets for blame when struggling peasants could not pay their debts. A religious heritage derived from Martin Luther further inflamed anti-Jewish attitudes, and the resulting lack of economic opportunity spurred several of Sigmar’s brothers to immigrate to America when he himself was still a child. The fortunes they went on to earn in oil wells, diamonds, and Canadian mines would later prove crucial to Sigmar’s maneuvers escaping the Nazis, while for their parents, money from America made it possible to quit Ihringen for the much larger and finer city of Freiburg.

After centuries of French and Austrian rule, Freiburg was almost 80 percent Catholic and, being so close to the western border, retained some of the egalitarian imprint of French political thought. Flourishing around an august university, it was a more liberal and cosmopolitan urban center, where the couple hoped to find greater religious tolerance, in addition to better schools for their youngest sons. As for Ihringen, Sigmar had such little regard for the town of his birth that he never again returned there or took his wife and children to see it, though it is a trip of barely ten miles. Today, the green Kaiserstuhl landscape between the two towns boasts vineyards whose grapes produce fine white wines—Sylvaner, Riesling, Traminer—and broad fields at the foot of the Tuniberg slopes, where white asparagus or

Spargel

grows thick and fleshy under dark blankets that shield it from the light of the sun.

When Sigmar, then nine, first moved with his parents to Freiburg in 1889, the city’s restored Jewish community was only twenty-six years old, following more than four centuries in which Jews had been banned. In records kept in the archives, I have pondered my great-grandfather’s registry there, including the fact that he and his wife were deemed “Israelites” by religion, which made them unusual. Jews had been permitted to start a synagogue in Freiburg in 1865 and a cemetery soon after. But by 1933, when Hitler took power, there were still only 1,138 Jews in the city, comprising just over 1 percent of the population, largely the same as in the rest of the country.

In high school in Freiburg, Sigmar excelled. It is a testimony to his hope in the Fatherland, his faith that reason or justice might eventually prevail, that he saved his report card and many other official papers in order someday to reclaim his valid German identity. I examine his schoolboy marks with the same maternal pleasure I have derived from the grades of my children, but it feels like spying somehow, this looking into the past to check my grandfather’s progress. From country to country, Sigmar carried these records in what he dubbed his

Köfferle

, a worn brown leather valise, filled with the incontrovertible documentary proof of exactly who he had been, and it therefore became his most valued possession.

How thankful I am, in my research, for our family compulsion to preserve every document and memento. Letters and pictures, drawings and poems, programs and matchbooks, old report cards, identity cards, postcards, and wartime transit papers. Graveside speeches, telegrams sent almost one hundred years past, birth announcements, the first heartfelt scribblings of children, lined ledgers of spending, and government records that detail a culture as well as a story of persecution. The will that Sigmar wrote out by hand on the eve of his marriage, and the dog-eared booklet of Hebrew prayers and psalms that the German Army provided for Jewish soldiers marching to battle in World War I. The documents stamped by the Nazis that systematically stripped Sigmar of all he once claimed—his name and his home as well as his nation. We are all casual archivists of family history, as if preserving these fragile treasures could stop time and make the people we love at least as enduring as onionskin paper.

Prior to the war, Sigmar’s wealthy American brothers provided the means for him to launch his iron, steel, and building supply business, starting in Mülhausen across the Rhine River. A bachelor, he had remained single after his mother’s death in 1907 to care for his father in Freiburg, and so he commuted to work until 1914, when he was called up to four years of infantry service. In postcards he wrote home from the front, Sigmar, then thirty-three, explained that after training in Konstanz with the 114th Infantry Regiment, he had been made a

Scheinwerfer

, manning battlefield searchlights. Were it not for a niece who scoured local farms to send packages of food to him daily, he would have gone hungry. Then he contracted rheumatic fever. Despite his ordeals, Sigmar stood proudly with his regiment, posing for his own wartime postcards. His demeanor suggests that this short Jewish soldier—with a thick mustache and sometimes a beard, wearing a high-buttoned uniform and a flat cap that covered the fact he had already lost most of his hair—was also a loyal German who would always revere Goethe, Nietzsche, Beethoven, and Wagner.

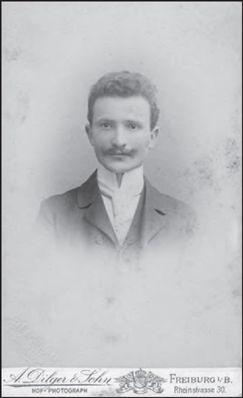

Sigmar as a young businessman in Freiburg

(photo credit 2.4)

A telegram handwritten in purple pencil that Sigmar received at the front on January 26, 1915—the same date inscribed on my great-grandfather’s tombstone—makes it clear that when Simon fell ill, his soldiering son could not have returned in time to see him alive. Bereft of his father, Sigmar decided to move to Mülhausen when he resumed civilian life after Germany’s defeat in the war. His older sister Marie and her husband, Paul Cahen, already lived in that city, though its contentious history sowed perennial troubles for those who considered it home, as control of the region shifted between the French and the Germans.

In the Franco-Prussian War of 1871, France had lost Mulhouse to Otto von Bismarck, who claimed Alsace and the neighboring province of Lorraine as part of his newly unified German nation. Renamed Mülhausen, the city was forced to accept German language and culture. The Germans treated the region as occupied enemy territory, even while drafting its men into their army. Almost fifty years later, the tables were turned. With France’s victory in World War I, the kaiser abdicated and went into exile. Mülhausen, along with the rest of Alsace and Lorraine, returned to French rule under the treaty signed in Versailles in 1919. Joyfully, the beleaguered city reclaimed its French name, and rancor toward Germany burned ever more fiercely.

Soon after Sigmar’s return from battle, his sister Marie arranged through a friend in Eppingen for him to meet Alice. At that point, the former wartime nurse was twenty-eight years old and all too aware that with so many young men having died in the war, she could not afford to be overly choosy. When the match was suggested, Sigmar was close to forty, shorter than she, a quiet, serious, and intellectual man whose chief enjoyments came from reading and playing the piano. Qualities that might lead strangers to view him as stern and unyielding somehow also lent him a charming, childlike aura of virtue. A person of straightforward standards and firmly held morals, Sigmar never spoke ill of anyone else and would not seek advantage over his neighbor. He adhered to the laws of the country he loved because he assumed they were there for Order and Purpose. Above that, he believed in a God who ruled the universe fairly, and doing whatever he could to assist in that goal, he strove to make sure that justice prevailed.

From a young woman’s perspective, there was probably little dashing about him beyond the strength and mystery that lay in his silence. Indeed, while Alice admired her reliable suitor, passion likely played no major role in inducing the playful, if bashful, former nurse to agree to the marriage, as she did after only two meetings. In the first, she served him squares of Swiss chocolate on a small silver tray and nervously poured sweet liqueur into colored-glass snifters barely larger than thimbles. In the second, she drifted to sleep and almost fell off her chair while Sigmar earnestly spoke with her eagle-eyed mother, immovably stationed with them as a chaperone.

Alice was twenty-eight years old and Sigmar nearly forty when they were introduced after the war

.

Ever after, Alice would pride herself for having shown something like wisdom and farsighted good sense in securing her future. Sigmar’s brother and business partner, Heinrich, was a far better-looking, more graceful man, but comparing her own solid mate to her vain and high-strung brother-in-law over the years, Alice concluded—and tried with little success to drill into her daughters—that looks meant nothing in choosing a husband. What counted, she knew, were virtues of character on which a woman could always depend.

Alice’s marriage took place in a hotel in Heidelberg, and Marie’s young daughter Emilie, or “Mimi,” entertained the small group of guests with Chopin piano mazurkas. A group portrait of the wedding party shows Alice, dressed in white ruffles, her eyes cast down shyly, slouching a little as if to disguise being taller than the unsmiling new husband who stands at her side. Sigmar, wearing a white bow tie and a gold watch chain looped over his tight buttoned vest, stares in dignified poise toward the future.