Chop Suey : A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States (28 page)

Read Chop Suey : A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States Online

Authors: Andrew Coe

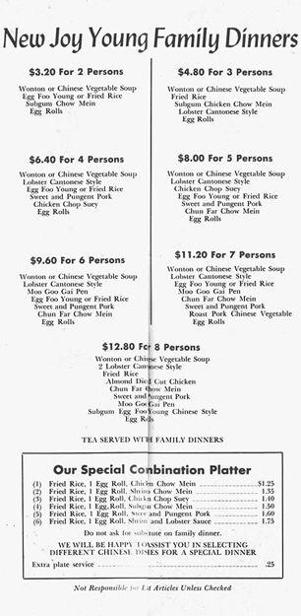

Figure 7.1. Inexpensive “family dinners,” like these offerings at New Joy Young in Knoxville, Tennessee, were the mainstay of 1950s Chinese-American restaurants.

In a 1954

Mad

comic strip entitled “Restaurant!” by the artist Will Elder, Dad decides to take the family for lunch on a typical Sunday afternoon in America.

2

Elder packed the piece with what he called “chicken fat,” visual gags that filled every corner of his panels. A lot of these are at the beginning: the nebbishy Sturdley family waits to be seated in a crowded restaurant filled with shouting, fighting customers, pets, flies in the soup, kids running around with chamber pots on their heads, stray characters from other comic strips, and so on. Next come the usual indignities: getting a booth, waiting for the greasy dishes of previous diners to be cleaned away, waiting for the waiter, and waiting for Uncle Smurdley to make up his mind. Finally, the chow mein arrives. Dad savors the aroma of crisp noodles, stewed onions, bean sprouts, strips of chicken, and snowy rice. Just as he’s about to put the first chopstick-full into his mouth, Baby announces that he has to go to the bathroom. Finally Dad is able to eat, but further humiliations ensue, including getting smacked on the head by the cute kid in the next booth. Afterward, the family vows to stay at home, only to find themselves once again—“eyeballs protruding, tongues gently lolling”—waiting for a booth at the same eatery the next Sunday. What’s remarkable about the scene Elder depicts (aside from his manic visual imagery) is how un-Chinese the restaurant is. You have to look closely to notice the red lanterns scattered here and there. Only one of the waiters appears to be Asian, and a peek into the kitchen reveals no Chinese but a bunch of sweaty, unshaven hash-joint cooks. Despite all this,

habit—and price—still pulled diners back to the Chinese American restaurants.

In and around cities like New York, Chicago, and San Francisco, some restaurant owners with deeper pockets experimented with changes in design and new menus. The classic Chinese restaurant aesthetic had not changed in decades: booths along the wall, tables in the center, lanterns hanging from the ceiling, a few cheap Chinese prints on the walls, a counter for the cash register, and a display of cigars and cigarettes by the entrance. In the late fifties, owners began to hire architects to convert their interiors into something dramatic and modern. Sometimes, they became a little too modern; the

New York Times

described Manhattan’s Empress restaurant as a “distracting” blend of contemporary Danish with Chinese influences: “the walls are of black and scarlet, the banquettes are of gold and the napkins of rich pink.”

3

This trend reached a peak in 1973, when the firm of Gwathmey Siegel Associates renovated Pearl’s Chinese Restaurant, then popular with Manhattan movers and shakers. The

Times

’s architecture critic praised the design’s elegance, sophistication, and simple geometric forms (which made the dining room reverberate with noise). However, at most restaurants where the modern décor was meant to complement the clientele’s taste, the menus remained the same.

In 1934, an ex-bootlegger and beach bum named Ernest Raymond Beaumont Gantt opened in Hollywood a nightspot he called Don’s Beachcomber. He served exotic rum drinks—including the Zombie, a concoction he’d invented—from a bar decorated with tropical motifs. Three years later, he revamped his establishment as the Don the Beachcomber restaurant, serving Cantonese food with a few Polynesian touches, mostly on the pupu platter. The concept was so successful that he changed his name to Donn Beach. The buzz

about it caught the attention of Victor Bergeron, the young owner of Hinky Dink’s Tavern, a bar in Oakland. He copied Don the Beachcomber’s rum cocktails, tropical look, and Cantonese menu and renamed his restaurant Trader Vic’s. He also added such creations as rumaki, crab Rangoon, and Calcutta lamb curry to his menus. However, the main culinary offerings of both restaurants were Cantonese: egg rolls, wonton soup, barbecued pork, almond chicken, beef with tomato, fried rice, and so on. By the 1950s, branches of Don the Beachcomber and Trader Vic’s had opened across the country, followed by a host of imitators, including many with Chinese owners. The Kon-Tiki Club in Chicago advertised: “Escape to the South Seas!” You could also enjoy a complete Cantonese dinner there for $1.85 to $3.25. (The low food prices were offset by bar profits and turnover in the large, often full dining rooms.) This craze for “Polynesian” restaurants with Cantonese food continued well into the 1970s, particularly in suburban New Jersey, where the commercial strips were dotted with colorful eateries like the Orient Luau, featuring a popular all-you-can-eat “Hawaiian smorgasbord.” (Today, the few that remain are patronized largely by senior citizens, baby boomers on nostalgia visits, and devotees of the revived Tiki bar cult.)

These gimmicks were not enough to save the classic Chinese American restaurant formula. By the 1960s, it was clear that chop suey, chow mein, egg foo young, and the like were ageing along with the Chinatown old-timers. The last of the “bachelor” generation (almost all male), who had grown up during the early decades of the Exclusion Act era and had manned Chinese kitchens across the United States, were slowly dying out. Restrictions had been eased, so new immigrants from China were finally beginning to enter the country. These changes had been incremental. First, the Magnuson Act of 1943 ended Chinese Exclusion and

allowed the Chinese people who were living in the United States to become naturalized citizens at last. Alien wives of citizens were admitted in 1946. In 1947, the War Brides Act opened the door to approximately six thousand Chinese brides of Chinese American soldiers. In San Francisco, the number of births to Chinese couples more than doubled. After the Communist takeover in China, further changes were made in immigration laws, allowing some political refugees from China to gain citizenship. In 1965, the Immigration and Nationality Act abolished quotas based on national origin and made reunification of families a priority, and thousands of immigrants streamed into the United States from Taiwan and Hong Kong, all of them bringing with them their food traditions. Increased communication between the Chinese American community and their families in East Asia reinforced the economic and cultural ties between the two regions. Slowly at first, Chinese food in the United States began a transformation.

The first glimmerings that Chinese food consisted of more than a small set of Cantonese American specialties came from a cookbook. In 1945, a Chinese immigrant, Buwei Yang Chao, published a little cookbook,

How to Cook and Eat in Chinese

. Trained as a doctor, Chao was born in 1889 in Nanjing, a large city in the lower Yangzi basin. She married a professor of philology, and they raised four daughters while her husband held teaching positions in China, Europe, and the United States. By World War II, the family was settled in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he taught at Harvard, and she began work on the cookbook. She had been raised in an upper-class family and had not learned to cook as a child. In a note, she tells us that she only began cooking while studying medicine in Japan: “I found Japanese food so uneatable that I had to cook my own meals. I had always looked down upon food and things, but I hated to

look down upon a Japanese dinner under my nose. So by the time I became a doctor, I also became something of a cook.”

4

Accompanying her husband on his research trips around China, she had studied regional cuisines while he studied regional dialects. She says she began to write her cookbook at the urging of a fellow faculty wife, but it’s clear that the suggestion struck some deeper chord within her, because

How to Cook and Eat in Chinese

is far more than a compendium of favorite dishes she served at faculty parties. With the help of her husband and her daughter Rulan, Chao set a more ambitious goal for herself: re-creating the traditional Chinese way of eating on United States soil.

She discusses this topic for fifty pages before presenting any recipes. First, she describes how the Chinese organize their meals, from breakfasts at home to big restaurant banquets. Here many readers first discovered congee and dim sum—“dot hearts,” in Chao’s translation—and learned of the intricacies of communal family meals and dinner party etiquette. Chao also delineates a number of China’s regional cuisines—for nearly the first time in English. Next, she broaches a delicate question: “Do you get real Chinese food in the Chinese restaurants outside of China? The answer is, You can get it if you ask for it . . . . If you say you want real Chinese dishes and eat the Chinese way, that is, a few dishes to eat in common and with chopsticks, then they know that you know.” She mentions the existence of only three eateries that are not Cantonese—Tianjin restaurants in New York and Washington and a Ningbo one in New York. Regarding the fare offered in the typical Cantonese restaurant, she comments:

Many times the trouble is that because the customers do not know what is good in Chinese food they often order things which the Chinese do not eat very much. The restaurant people, on their part, try to serve the

public what they think the public wants. So in the course of time a tradition of American-Chinese food and ceremonies of eating has grown up which is different from eating in China.

5

That’s a nice way of saying she doesn’t recognize chop suey and chow mein as Chinese, although she does include a recipe for American-style egg foo young. She goes on to systematically discuss raw materials, seasonings, utensils, and cooking methods. Finally come the recipes; in this part of the book, she subverts the normal cookbook order of rice, soup, and main dish by beginning with meats and ending with rice and noodles. The sense of unfamiliarity is further heightened by the book’s many word coinages, for example “wraplings” (pot sticker–type dumplings) and “ramblings” (wontons), which enhance the reader’s sense that this isn’t the Chinese food they’ve tried but something new and interesting.

When

How to Cook and Eat in Chinese

appeared, Jane Holt, a

New York Times

food writer, called it “something novel in the way of a cook book.” Although she disavowed expertise on the subject, Holt said “the book strikes us as being an authentic account of the Chinese culinary system, which apparently is every bit as complicated as the culture that has produced it.”

6

Repeatedly cited in succeeding years as the best cookbook for those interested in Chinese cuisine, the book continued to sell; after the 1968 third and final edition, reprints appeared well into the 1970s. It’s difficult to judge how many people actually prepared the recipes in

How to Cook and Eat in Chinese

, but it’s clear that fans often returned to the book to help them understand the culture of Chinese food and guide them toward new eating experiences.

In the years after World War II, restaurants opened that pioneered a new taste in Chinese food. The entrepreneurs behind them were often either Chinatown businessmen

frustrated with the low profits and cultural embarrassment of the chop suey joints or members of China’s elite, mainly academics and diplomats, who had been stranded abroad by war and then the Communist takeover. The Peking Restaurant on Connecticut Avenue in Washington, D.C., one of the first, was founded in 1947 by C. M. Loo—once a Chinese diplomat’s chef and later the butler at the Chinese Embassy—along with four partners. The menu featured “Peking Style Native Foods,” including moo shu pork and the house specialty, Peking duck. Patrons included members of the local diplomatic community and many “China hands” who had fallen in love with Chinese food during their service in mainland China. The groundbreaker in San Francisco was Kan’s, the brainchild of Johnny Kan, a local businessman:

Our concept was to have a Ming or Tang dynasty theme for décor, a fine crew of master chefs, and a well-organized dining room crew headed by a courteous maitre d’, host, hostesses, and so on. And we topped it off with a glass-enclosed kitchen. This would serve many purposes. The customers could actually see Chinese food being prepared, and it would encourage everybody to keep the kitchen clean.

7

Kan’s sought to revive the tradition of the high-end banquet restaurants that had flourished in San Francisco in the nineteenth century. Customers who wanted to order chop suey were not so gently encouraged to order something else. The thick menu, not limited to Cantonese cuisine, listed expensive dishes like bird’s nest soup and Peking duck. Soon enough, culinary tourists streamed to Chinatown for dinner at Kan’s or upscale competitors like the Empress of China and the Imperial Palace. Many were locals: a century after its arrival, San Franciscans were now eager to spend serious money for Chinese food.

In 1961, a new restaurant called the Mandarin opened up in a hard-luck location outside Chinatown. Its owner, Cecilia Chang, had lived through the some of the most dramatic events in modern Chinese history. Born into a wealthy family, she had been forced by the Japanese invasion to flee for 2,500 miles, largely on foot and wearing dirty peasant clothes as a disguise. She married a Nationalist diplomat and then fled again, this time to Japan to avoid the Communist takeover. By 1958, she had arrived in San Francisco, where she decided to open a restaurant: “I named the restaurant the Mandarin, and selected dishes for the menu from northern China, Peking, Hunan and Szechwan: real Chinese food, with a conspicuous absence of chop suey and egg foo young.”

8

With the backing of influential columnists like Herb Caen, the Mandarin was a success, introducing dishes like tea-smoked duck, pot stickers, and sizzling rice soup. By 1968, the restaurant had expanded to three hundred seats and become even more elaborate, featuring fine Chinese paintings and embroideries and an open Mongolian barbecue. Meanwhile, other restaurants bearing the name Mandarin and featuring non-Cantonese food were opening across the country, with a large cluster in Chicago. In New York, the first was Mandarin House, owned by Emily Kwoh, a Shanghai native. She had entered the restaurant business in the mid-1950s with the Great Shanghai at Broadway and 103rd Street, serving food from three menus: Cantonese, American, and Shanghai. (For the next three decades, the stretch of upper Broadway from Eighty-sixth to 110th Street was a mecca for Chinese food aficionados.) At Mandarin House, which opened in 1958, Kwoh served non-Cantonese specialties like beggar’s chicken, sesame-sprinkled flatbread, and, most important,

mu xu rou

(moo shu pork).