Chop Suey : A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States (27 page)

Read Chop Suey : A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States Online

Authors: Andrew Coe

Over time, American Jews noticed many similarities between their food and Chinese cuisine, including the use of garlic, onions, celery, and chicken and the avoidance of milk. Nevertheless, they still had to address the issue of kashrut and the prevalence of shellfish and pork. For those who followed the letter of Jewish law, Chinese food was definitely

treyf

(unclean). But there is a tradition in Judaism of devising interpretations that find loopholes in the law in order to allow people some room to live. When faced with the question of how to eat Chinese food and keep their Jewish identity, hungry and creative minds came up with the idea of “safe treyf”—food that is unclean but okay. A pork chop was still forbidden, but pork chop suey was okay, because the meat was sliced into little pieces and hidden under a

mound of sauce-drenched vegetables. (There’s definitely a streak of humor running through the concept of safe treyf.) Though almost always flavored with ham, Chinese soups were also permitted, because the pork was invisible. As for the shrimp and lobster? Somehow serving them in a Chinese restaurant converted them into acceptable foods, perhaps because the cooks and waiters were both non-Christian and even more alien in America than Jews. They would have felt much less comfortable eating in, say, a neighborhood Italian restaurant, because the memory of Europe’s long history of Christian persecutions of Jews was fresh in their minds. The very newness of Chinese food gave them room to find a way to make it their own. During the next three decades, American Jews came to be identified as the minority group with a taste for eating Chinese.

As chop suey became Americanized, one group was relegated to the sidelines and almost forgotten: the Chinese themselves. Compared to the days in the 1880s when the Chinese had feared for their lives, this was an improvement. They had the ability to run their businesses without fear that a mob was around the corner ready to burn their homes and drive them from town. A new vision of the Chinese gradually supplanted the old prejudices—particularly after Japan invaded China in 1937, when Americans began to see the Chinese first as victims and then, as they fought back, plucky freedom fighters. At the movies, wise, old Charlie Chan supplanted evil, hissing Fu Manchu. However, Chinese Americans still led lives on the margins of society. The Exclusion Act remained in force; immigration from China was banned, and Chinese still could not become American citizens. After the onset of the Great Depression, travel back to mainland China became much rarer. The ratio of males to females had improved (4:1 versus 25:1 in 1890), but the majority of Chinese residents still died childless. If trends

continued, the country’s Chinese population would dwindle away to nothing.

The one exception to this gloomy picture was the Territory of Hawaii, where Chinese had for decades dominated the restaurant industry. Chinese had begun to arrive in Hawaii back in the late eighteenth century. Between 1850 and 1882 (the advent of the Chinese Exclusion Act), thousands of contract laborers from Guangdong Province were brought to work in the islands’ sugar industry. They were joined by South Chinese entrepreneurs who founded trading companies and stores, many based in Honolulu’s nascent Chinatown. The Chinese Hawaiians were mainly Cantonese from the Zhongshan district (near Macau) of the Pearl River Delta and members of the Hakka ethnic group from eastern Guangdong. Like the Chinese adventurers who traveled to other parts of the New World, they brought their cuisine with them, mainly Cantonese and Hakka peasant fare. In the countryside, they opened general stores that also served Hawaiian and American food. In Honolulu, they owned most of the city’s cheap cafés. For the Chinese themselves, the place to eat was Chinatown, where they could enjoy the rural fare of the Pearl River Delta, mainly various kinds of soups, congees, noodle dishes, and dumplings. The Wo Fat restaurant, opened in 1882, was reputed to be the favorite of a young Zhongshan native named Sun Yat-Sen, who became one of China’s most revered revolutionary leaders. In 1901, at least one Honolulu restaurant existed where one could order more sophisticated banquet food—“preserved chicken, shark’s fin, fresh lotus nest, duck, edible bird’s nest with chopped chicken, preserved yellow fish heads, preserved snow lichen, almonds and fresh turquoise [turtle?], gold coin chicken, [and] Chinese fancy tarts”

23

—but this was the exception.

In 1890, 20 percent of Hawaii’s population were Chinese; thereafter, their numbers slowly dwindled due to harsh

immigration restrictions. Nevertheless, the Chinese retained an important role in the islands’ life, mainly as farmers, merchants, and factory owners. Many intermarried with local Hawaiians, with an accompanying blending of cultures, and missionaries were pleased to note a surprisingly large number of Chinese converts to Christianity. As tourism from the mainland boomed, the demands and expectations of the visitors necessitated changes in the local businesses: most Chinese restaurants added “chop suey” to their name—Wo Fat became Wo Fat Chop Suey—so that the tourists would know what to expect. Nonetheless, the Chinese Hawaiians relied on their numbers, cultural strength, and proximity to China to keep their traditions alive. In 1941, the Chinese Committee of the Honolulu YWCA compiled a cookbook entitled

Chinese Home Cooking

; it was probably compiled by Mary Li Sia, a cookbook author and the YWCA’s Chinese cooking instructor. The book’s well over a hundred recipes unabashedly exhibit local Chinese tastes, including gingered pigs’ feet, bitter melon with beef, abalone with vegetables and gluten balls, numerous “long rice” (rice noodle) dishes, and nine varieties of chop suey. Their mode of preparation might not have been exactly what the tourists remembered from back home, but they were outnumbered by the palates and wallets of Chinatown residents. The Chinese Hawaiians retained their distinctive culinary culture far longer than their compatriots on the mainland.

During the 1930s and 1940s, Chinese Americans continued to rely on restaurants and family laundries for their economic survival. However, they now had competition; big mechanized laundries were putting the Chinese laundrymen out of work. And they had lost their monopoly on chop suey and chow mein as Americans learned to cook the dishes, and with Prohibition over, non-Chinese nightclubs were now crowding out the vast chop-suey-and-dancing halls. There

were still twenty-eight Chinatowns across the country, but the only ones where the populations were increasing were those in San Francisco and New York. In a striking reversal, the largest, in San Francisco, was now famous not as a dingy and mysterious ghetto but as a bright, modern tourist trap:

Indeed, Chinatown today is not only clean but quaint, a sort of permanent exhibit of the Orient, colorful and exotic, set down amid the gray uniformity of American city life. The architectural and decorative embellishments of its buildings are often typically Oriental in color and design. Here are shops which allure tourists with displays of Oriental art, and josshouses on the upper floors of “benevolent association” buildings, where friendly guides sound deep-voiced gongs, burn incense, shake the fortune-telling sticks before the gloriously carved and colored shrine of Kwan-yin, the goddess of mercy, and dispense souvenirs—for a consideration!

24

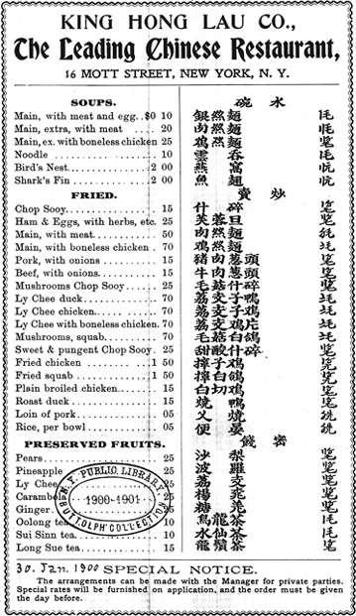

The main streets of the two most important districts—Grant Avenue in San Francisco and Mott Street in New York—were lined with blinking chop suey signs and curio shops. In the side streets, the Chinese themselves conducted their business—in grocery stores, tea shops, doctor’s offices, noodle factories, printing shops, and bakeries. Indeed the Chinatowns of these two cities were the central manufacturing and distribution points for a wide range of products necessary for Chinese eateries, from imported tea and soy sauce to almond cookies and restaurant menus. These goods were shipped from New York to restaurants east of the Mississippi; San Francisco handled the trade for the western half of the country.

The Chinatown restaurants of New York and San Francisco were of two types: those catering to Chinese diners and

those primarily feeding everyone else. In 1939, the Chinese needed big banquet restaurants as much as the Chinese in 1865 San Francisco had—for events like holidays, weddings, anniversaries, and business gatherings. That year, the Committee to Save China’s Children hosted a fundraising banquet at the China Clipper restaurant on Doyers Street in New York’s Chinatown that featured bean curd soup, brown

stewed duck with almonds, diced squab with Chinese vegetables, chicken with “Chinese brown cheese” (bean curd), Cantonese noodles, sweet and pungent shrimp, rice, dessert soup, and lotus wine. This was real Cantonese banquet fare, albeit the relatively restrained Sze Yap version. Meanwhile, at Lum Fong’s over on Canal Street, the mainstays were chop suey, chow mein, egg foo young, yat gaw mein, fried rice, tomato beef, pepper steak, and egg rolls—an item Lum Fong claimed to have introduced to American menus. For a dollar or two more, diners could order moo goo gai pan (chicken with mushrooms), lobster Cantonese, shrimp with lobster sauce, and a few other specialties. Some eateries also listed fried wontons, which they described as

kreplach

(Yiddish for small, meat-filled dumplings). In other parts of the United States, the Lum Fong’s type of Chinese American menu was the only game in town. If one wanted more interesting dishes, one could usually call ahead and order off the menu. A Chinese family in Omaha, Nebraska, could probably find a reasonable Cantonese meal in that city. But you had to know that possibility existed and want to act on that knowledge. Around the early 1940s, the menus in Chinese restaurants stopped evolving. Their food stagnated into bland and unexciting dishes that were now far removed from the preparations of the Pearl River Delta; and they were losing ground to the competition. The magic and excitement were gone from Chinese food. Unless something changed, Chinese restaurants were in danger of fading away into obscurity.

Figure 6.5. In 1900, Mott Street’s King Hong Lau served white patrons noodle soups and chop suey, with tea and sweets for dessert.

Devouring the Duck

In the decades following World War II, Chinese restaurant owners hung on by adapting their businesses to changes in the larger society. They followed Americans out of the center cities, opening eateries in new suburbs like Levittown, New York, and Park Forest, Illinois. There they encountered competition from the new fast food hamburger stands, fried chicken restaurants, and pizza parlors that were catering to hungry, busy Americans. To compete, Chinese restaurants capitalized on one of their longtime strengths: the ability to sell large portions of inexpensive food. The centerpiece of their menus was the “family dinner,” a multicourse meal of Cantonese American favorites for one low price. The cheapest two-person family dinner at New Joy Young in Knoxville, Tennessee, featured four courses: wonton or Chinese vegetable soup, egg foo young or fried rice, subgum chow mein, and egg rolls, all for $3.20. (Some restaurants divided the choices into columns; hence the “one from column A and one from column B” that many associate with eateries from this era.) For only $1.25, you could enjoy fried rice, one egg roll, and

chicken chow mein. You could also order à la carte dishes: lobster Cantonese, moo goo gai pan, American steaks, lobster Newburg, and sandwiches. For better or worse, the cheap, familiar Chinese dinners drew the most customers.

The trials of the Chinese restaurant business were outlined in a 1958 article in the

Washington Post

. There were 110 Chinese eateries in the District of Columbia, and for most of them business was not good: “A few restaurants turn a tidy profit; others supply a comfortable income; many furnish a bare subsistence.” The leaders of the local Chinese community considered the restaurant business moribund, an enterprise that had less and less to do with the Chinese-ness of its product. One businessman complained to the reporter about the restaurant owners: “They have to do a job of public relations. They have to improve their food, their service, their atmosphere. A Chinese restaurant should have pleasant Chinese surroundings—not chrome and neon and juke boxes. Why look how Washington has grown. But the Chinese restaurants haven’t.”

1

One of the many problems was that young cooks with any ambition refused to work for $4,000 a year, so most of the food was prepared by old-timers whose methods were mired in the past. Some of the larger restaurants had attempted to import trained chefs from Hong Kong or Taiwan but had run into prohibitive immigration restrictions.