Chop Suey : A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States (31 page)

Read Chop Suey : A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States Online

Authors: Andrew Coe

Figure 7.3. Adroitly wielding her chopsticks, Mrs. Nixon enjoys some spicy eggplant on her visit to the kitchens of the Peking Hotel, February 1972. The White House used the interest in Chinese food to distract attention from more substantive issues.

For the Chinese, the evening was far more than just another state dinner; it was also a coming-out party, a signal to the world that the People’s Republic was emerging from twenty-two years of self-imposed isolation. They planned every phase of the event with meticulous care, mobilizing their nation’s limitless human resources, shipping in the best ingredients, and requisitioning the top hotel and restaurant chefs for the kitchens at the Great Hall of the People. While there had never been any question whether the banquet would follow Chinese standards of cuisine and service, certain limits had been imposed. For the past seven months, the Chinese had been testing the culinary sophistication of the Americans visiting China on the advance trips. After these trials, the Chinese protocol staff had given the Americans one guarantee: President Nixon would not have to eat sea cucumbers during his China visit.

The Nixons arrived in a boxy, Chinese-made “Red Flag” limousine and entered the Great Hall of the People, passing under a huge portrait of Chairman Mao. Zhou Enlai escorted them up a grand staircase for photographs and then down a long receiving line into the banquet hall itself. Here

the American TV networks picked up the story. Back in the States, millions of Americans eating breakfast watched the cameras pan over the empty tables and the white-jacketed waiters standing at attention, as the reporters desperately tried to fill the time. Barbara Walters of NBC commented to Ed Newman back in New York: “We had our first taste of food and, Ed, you know what? It tasted like Chinese food! We had been told that it was so very exotic and so different that we might not recognize it, but we did indeed—it’s just better than the Chinese food that we get in our country.” She also revealed that the Chinese serve their “most esteemed” foreign guests nine-course banquets, while lesser visitors receive fewer courses.

Finally President Nixon and Premier Zhou Enlai entered, and the meal began under the glare of the television lights at the big round table next to the stage. In addition to the cold hors d’oeuvres—salted chicken, vegetarian ham, cucumber rolls, crisp silver carp, duck slices with pineapple, three colored eggs (including thousand-year-old eggs with their aroma of sulfur and ammonia), and Cantonese smoked salted meat and duck liver sausage—a sharp-eyed viewer could spot big rosettes of butter and slices of white bread at every place. The barbarians would not have to sneak loaves in their pockets. Walters was awed at what she was seeing: “Mrs. Nixon using chopsticks!” The perfect Chinese host, Zhou selected a delicacy from one of the dishes and gave it to Mrs. Nixon. She gingerly pushed the food around her plate for a minute or two, finally inserted something into her mouth, and ever-so-slowly began to chew. Watching from New York, Ed Newman observed: “I think we can also see that President Nixon is using chopsticks and apparently doing very well with them.” Over on ABC, Harry Reasoner was also impressed: “Here is a tremendous picture: the President of the United States with chopsticks!” The next day, the

New

York Times

television critic wrote: “Some images were simply beyond words or still photographs,” including the sight of “Mr. and Mrs. Nixon carefully wielding chopsticks.”

Chopsticks were quickly forgotten as Zhou rose to toast the friendship of the Chinese and American peoples. The reporters declared that he was “warm and gracious” and had dispelled the chill that had descended at the airport. Then Nixon took the stage and read his toast, suggesting that the two nations should, in the words of Chairman Mao, “seize the day, seize the hour.” After complimenting the chefs for preparing such a magnificent banquet, Nixon descended to toast each top Chinese official with mao-tai. He didn’t forget his instructions: the level of drink in his glass hardly dropped. The president, Dan Rather opined, looked “energetic and triumphant.” For two more hours, the meal continued, through entrées including spongy bamboo shoots and egg-white consommé, shark’s fin in three shreds, fried and stewed prawns, mushrooms and mustard greens, steamed chicken with coconut, and a cold almond junket for dessert. These were served with assorted pastries, including purée of pea cake, fried spring rolls, plum blossom dumplings, and fried sweet rice cake. Finally came a simple dessert of melon and tangerines, and then the banquet ended. For those present, it had been an amazing, history-making evening, even if the details were a bit vague after all those firewater toasts. Of all the Americans present, only Charles Freeman, the veteran of Taipei’s dining scene, opined the meal’s offerings had merely been “very good, standard Chinese banquet food.”

The American television audience did not see the entire banquet because the networks cut back to their regular programming right after the toasts. Before that happened, the viewers received a message from their sponsors. On CBS, McDonald’s promoted its deep-fried cherry pies to celebrate

Washington’s Birthday. Meanwhile, over on NBC was heard the bouncy jingle “East meets West. La Choy makes Chinese food

swing

American. La Choy makes Oriental recipes to serve at home.” A crisply coiffed nuclear family sat in a spotlessly white dining alcove. A baritone voiceover announced: “Let East meet West at your home. Enjoy La Choy Chicken or Beef Chow Mein. Exotic recipes from scratch? Use La Choy ingredients: Chinese vegetables, bean sprouts, water chestnuts, soy sauce.” The camera closed in on the family smiling down at a serving platter in the center of the white table: a mound of steaming chicken chow mein. Given the moment, La Choy’s ad buyers may have thought this savvy marketing. They did not realize, however, that the coming fad for Chinese food would include everything but chop suey and chow mein.

Even before Nixon departed, Americans had been going crazy for things Chinese—a reprise of the China fad during Li Hongzhang’s visit. People were swarming to classes in Mandarin and in Chinese cooking; department stores sold Chinese handicrafts (the Mao suits quickly sold out at Bloomingdale’s in New York); publishers rushed books on the People’s Republic into print; and Chinese restaurants suddenly began to fill up. After they saw the images of Nixon eating banquet food in Beijing, customers began to use chopsticks and ask about sharks’ fin soup and Peking duck. In New York, Chicago, and Washington, D.C., restaurant owners anxious to cash in on the trend quickly whipped up special nine-course menus that supposedly replicated Nixon’s meal with Zhou Enlai. In response, Taiwan’s government flew in a team of chefs to show that they were the true guardians of Chinese culinary tradition. Banquet fever lasted for weeks—the first time Americans chose that most sophisticated format for a Chinese meal. Yet as they threw themselves into new eating experiences, they discovered

that they needed a new set of skills to properly enjoy Chinese cuisine. That included ordering the right balance of contrasting (soft vs. crunchy, fried vs. boiled, etc.) dishes, selecting the correct beverage, using chopsticks, eating communally, and making sure that the food was prepared to Chinese and not American tastes. The ability to read and speak a little Chinese couldn’t hurt either. If all else failed, the

Wall Street Journal

advised: “put yourself in the chef’s hands by letting him decide the menu based upon what’s fresh in the kitchen that day and what he feels like creating. But be sure to let him know you are capable of enjoying his extra efforts. Chinese chefs, perhaps the most artistic in their profession, love appreciative clients.”

18

And diners appreciated the food. During the recession of the 1970s, when many high-end restaurants, including the famous Le Pavillon, went out of business, Chinese eateries flourished and expanded, particularly those serving adventurous new menus. Shortly after Nixon’s trip, the owners of the Shun Lee restaurant empire further jolted the food world by introducing a new Chinese regional cuisine: Hunan, which they advertised as “hot-hot-hot.”

Their restaurant, called Hunam, immediately earned four stars from the

New York Times

and was followed by imitators like Uncle Tai’s Hunan Yuan. In 1974, Henry Chung opened his Hunan Restaurant in San Francisco, probably the first such eatery west of the Mississippi. The original list of Hunan specialties served in the United States included harvest pork, beef with watercress, and honey ham with lotus nuts. Soon diners also began to notice a dish of chicken chunks in a savory, spicy sauce. Shun Lee called it “General Ching’s Chicken”; other eateries called it “General Tso’s Chicken.” The restaurant impresario David Keh told Roy Andries de Groot of the

Chicago Tribune

a complicated story of how General Tso, a real military hero, had invented the dish in his retirement, when he had “turned his creative energies to the development and improvement of the aromatic, peppery, spicy Hunanese cuisine.”

19

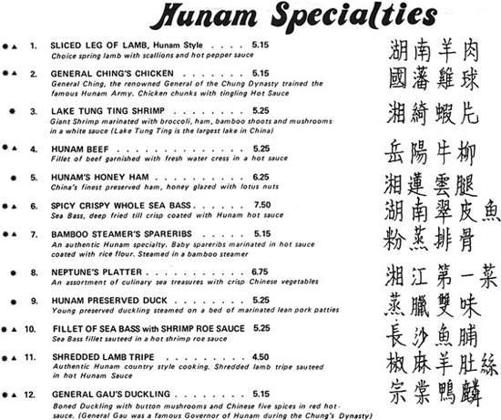

Figure 7.4. In 1972, the Hunam restaurant introduced diners to the “hot-hot-hot” caisine of China’s Hunan province. General’s chicken and Lake Tung Ting Shrimp are now served by Chinese restaurants across the country.

In reality, however, the chef who invented General Tso’s chicken, Peng Chang-kuei, was then cooking on East Forty-fourth Street in Manhattan. Born in 1919 in the capital of Hunan Province, Peng had been apprenticed to one of Hunan’s most prominent chefs and ended up, after the Communist takeover, in Taiwan. There he met President Chiang Kai-shek, who appreciated his cooking skills and invited him to prepare banquets for VIPs and foreign visitors. During this period, he invented a number of signature

dishes, including General Tso’s chicken, made from chunks of dark meat chicken marinated in egg whites and soy sauce. After being quickly deep-fried, the chunks are stir-fried with ginger, garlic, soy sauce, vinegar, cornstarch, sesame oil, and dried chili peppers. Chef Peng named it after the general because he admired this hero from his home province. Many young chefs who later moved to the United States learned how to make his dishes, including Chef Wang of Shun Lee and Uncle Tai. Word of their success reached Chef Peng, and in 1974 he decided to try his luck in New York. His first restaurant, Uncle Peng’s Hunan Yuan on East Forty-fourth Street, quickly went bust, leaving him nearly broke. Unwilling to return to Taiwan in shame, he borrowed from friends and opened the Yunnan Yuan restaurant on Fifty-second Street. Before long, its prime patron was Kissinger, fresh from opening China. Building on this hard-earned success, Chef Peng returned to the Forty-fourth Street location and opened his most famous U.S. restaurant, simply called Peng’s. In 1984, he decided he had proved his mettle and that it was time to return home. He sold his restaurants and moved back to Taiwan, where he started his chain of highly successful Peng Yuan restaurants. His most famous dish had already spread from Manhattan to the suburbs and then across the United States, changing every time a new chef prepared it. Already in 1978, a dish of General Tso’s served in New Jersey was described as “slightly peppery, batter-fried chicken.”

20

The adaptation of Hunan and Sichuan food to American tastes was well under way.

While Americans celebrated their love affair with spicy Chinese food, another great change was taking place. For the first time in a century, waves of Chinese immigrants began arriving in the United States. They came not only from Hong Kong and Taiwan as in decades past but also from Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, Burma, Thailand, and, most

significantly, the People’s Republic of China. The Cantonese among them, already linked to the United States by family and clan associations, usually settled in existing Chinatowns—most importantly, in Manhattan and San Francisco. Others sought a fresh start, building Chinese communities in neighborhoods like Flushing, Queens, and Sunset Park, Brooklyn, both a quick subway ride from jobs in Manhattan. On the West Coast, the most vital Chinese district was founded in Monterey Park, a city in Los Angeles County’s San Gabriel Valley. Wherever these Chinese immigrants settled, they opened restaurants. Filled with Taiwanese, Monterey Park was dubbed Little Taipei and boasted dozens of Taiwan-style eateries catering primarily to recent immigrants. Other parts of the country saw the appearance of establishments specializing in dishes from Shanghai, Fujian, Chaozhou, Dongbei (China’s far northeast), Xinjiang, the Hakka ethnic group, and the Chinese communities in Singapore, Vietnam, Malaysia, and even Cuba. Not to be outdone, the Cantonese opened sprawling banquet halls doubling as lunchtime dim sum parlors, like New York City’s HSF (short for Hee Seung Fung). (San Franciscans yawned at this development—they had been eating Chinese tea pastries for a hundred years.) From the 1980s on, Chinese food flourished wherever new immigrants congregated.

Meanwhile, the owners of the Sichuan and Hunan restaurants improved their business skills, smoothing out the uncertainties. The epicenter of this transformation was “Szechuan Valley” (also known as “Hunan Gulch”), the stretch of Upper Broadway in Manhattan where nearly every block had its Sichuan or Hunan restaurant. Now managers standardized their menus so that they didn’t need a temperamental and high-priced artist to make the dishes, just a team of competent Chinese cooks. The offerings at Empire Szechuan, which grew into a chain that covered Manhattan, included not only Sichuan-style dishes like Ta Chien chicken, Kung Pao shrimp, and beef with broccoli but lobster Cantonese, egg drop soup, and chicken chow mein. (By 1993, you could also order sushi, teriyaki chicken, dim sum, and low-fat steamed vegetables with brown rice at Empire Szechuan.) And the recipes were altered once more to appeal to local, non-Chinese tastes. Shun Lee’s Michael Tong noticed that “Americans like anything spicy, anything sweet, anything crispy.”

21

At many eateries, chefs now dunked their cubes of meat in a thick all-purpose batter, deep-fried them, and served them in different slightly spicy, cloyingly sweet sauces. In order to maximize trade, owners also began offering delivery, slipping thousands of folded paper menus under apartment doors across Manhattan. No longer did you have to wait in line on a freezing winter night to get a table: one phone call, and the food would be at your door in twenty minutes. Business boomed, but the connection with customers was lost—it was far too easy to eat at home.