Blood Brotherhoods (34 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

The association’s aim is to bully landowners, and thereby to force them to hire stewards, guards, and labourers, to impose contractor-managers on them, and to determine the price paid for citrus fruit and other produce.

From these simple first steps, Sangiorgi advanced a long way. He got the chance to confirm what he knew about the mafia’s initiation ritual. And he ended by listing the bosses, underbosses and over two hundred soldiers in eight separate mafia cells. He exposed their links beyond Palermo—even as far as Tunisia, an outpost of the citrus fruit business. He explained how they came together for meetings and trials, and how they performed collective executions of any members deemed to have broken the rules—especially the rule that stipulated blind obedience to the bosses’ wishes. Sangiorgi

even named the mafia’s ‘regional or supreme boss’, the fifty-year-old citrus fruit dealer and

capo

of the Malaspina

cosca

, Francesco Siino.

The Siino name echoed in Sangiorgi’s memory. Francesco’s older brother Alfonso, now in charge of the Uditore branch of the sect, was one of the two hit men who shot dead old man Gambino’s son in 1874, and then went unpunished thanks to the ‘fratricide’ plot. Many other names in Sangiorgi’s report rang a malevolent bell: names like Cusimano, and above all Giammona. Antonino Giammona was the poetry-writing boss whose gang’s initiation ritual Sangiorgi had exposed in 1876. The old mobster was now close to eighty, but he still carried huge authority.

He gives direction through advice based on his vast experience and his long criminal record. He offers instructions on the way to carry out crimes and construct a defence, especially alibis.

Linking these surnames there was now much more than a shared history of murder and extortion. While Ermanno Sangiorgi, beset by the stresses of his police career, was struggling to hold his own small family together, the hoodlum clans of the Palermo hinterland had intermarried, and many had passed on their wealth and authority to their offspring: Antonino Giammona’s son Giuseppe was

capo

in Passo di Rigano; Alfonso Siino’s boy Filippo was underboss in Uditore. A generation on from his last encounter with the Palermo mob, Sangiorgi could see that the mafia’s marriage strategising had founded criminal dynasties. If the structure of bosses, underbosses and

cosche

gave the mafia its skeleton, then these kinship ties were its bloodstream.

Sangiorgi also identified intimate ground-level contacts between this new criminal nobility and some of Palermo’s longer established dynasties, among them the richest family in Sicily, the Florios. The head of the house of Florio, Ignazio, was a fourth generation entrepreneur whose father had married into some of the bluest blood in Sicily. The fortune that Ignazio inherited included the principal stake in NGI, the shipping company whose share price was covertly pumped up with Bank of Sicily money. A man of dash and style who was not yet out of his twenties when Sangiorgi became chief of police, Ignazio set the decadent tone in the Sicilian

monde

. Florio turned Palermo—or Floriopolis, as it became known—into a prime destination for the European yacht set. His sumptuous villa, located in its own parkland amid the fragrant hues of the Conca d’Oro, was the epicentre of polite society. But as Sangiorgi discovered, the Florio villa was also an important place for the Sicilian Honoured Society.

The men responsible for security at the Florio villa were the ‘gardener’, Francesco Noto and his younger brother Pietro—respectively the boss and

underboss of the mafia’s Olivuzza

cosca

. Sangiorgi did not discover just what were the terms of the deal between the Noto brothers and Ignazio Florio. But protection was almost always how

mafiosi

got their foot in the garden gate. Kidnapping was a serious risk, the Notos would have explained to Ignazio Florio, deferentially. But we can make sure of your safety. And once the Florios’ safety was in the hands of the mafia, there was no limit to the turns the relationship might take—many of them mutually beneficial. Having murderers to call on can be a very tempting resource.

One morning in 1897 Ignazio Florio woke to learn that his safety had been scandalously compromised: the villa had been broken into, and a large number of

objets d’art

were missing. He summoned the Noto brothers and delivered a humiliating tirade. A few days later, Florio woke up again and found that the stolen valuables had reappeared during the night—in exactly their original positions. This was a criminal gesture of astonishing finesse: both an apology, and a serene reminder of just how deeply the mafia had penetrated the Florio family’s domestic intimacies.

Sangiorgi learned that the culprits in the Florio burglary were two of the Notos’ own soldiers, who were unhappy because they felt they had not received a fair share of some loot from a kidnapping. The Notos strung the burglars along, promising more money on condition that the Florios’ property was put back—which it duly was. Then they reported the episode to a sitting of the mafia tribunal, which ruled that it was an outrageous act of insubordination. Several months later, in October 1897, an execution squad comprising representatives from each of the eight mafia

cosche

lured the burglars into a trap, shot them dead, and heaved their bodies into a deep grotto on a lemon grove.

What shocked even Sangiorgi about the whole story was that the Noto brothers had told the Florios just what they had done to the burglars. In November 1897, soon after the police had found the bodies in the grotto, but before anyone outside the mafia had the slightest idea how and why they had ended up there, Ignazio Florio’s mother was heard explaining that the dead men had been punished for the break-in earlier in the year. Justice had been done—discreetly and with due force—to the satisfaction of both the Florios and the hoodlums they sponsored. A kind of justice that could never have anything to do with the police.

The Florios inhabited a world of garden parties and gala balls, of royal receptions and open-top carriage rides, of whist soirées and opera premieres. An inconceivable distance separated their milieu from the ratrun tenements where the Neapolitan camorra was incubated, or from the dung-strewn hovels of Africo’s

picciotti

. Yet between the Florios and the Sicilian mafia there was almost no distance at all. If it came to an ‘open

fight’ between the state and the mafia, there was little doubt about which side the House of Florio would take.

On the night of 27 April 1900 Sangiorgi ordered the arrest

en masse

of the Men of Honour named in his reports. He hand-picked his officers, trusting his judgement of their honesty and courage. Even so, Sangiorgi had to keep the operation a secret until the last minute to avoid leaks: the mafia’s spies were everywhere. By October the Prefect of Palermo reported that Sangiorgi had reduced the mafia to ‘silence and inactivity’. That silence was the reward for months of brilliant policework. But it was also the mafia’s response to what had now happened to its favourite Member of Parliament, don Raffaele Palizzolo.

F

OUR TRIALS AND A FUNERAL

B

ETWEEN

N

OVEMBER

1899

AND

J

ULY

1904

THE MAFIA ISSUE WENT ON A NATIONAL

tour. Prime Minister General Luigi Pelloux had to put direct pressure on the Palermo prosecutors’ office to make sure the Notarbartolo murder finally came to court. The case was transferred away from Palermo lest the peculiar local atmosphere influence the outcome. There would, in the end, be three Notarbartolo murder trials, each in a different Italian city, each covered in depth by the country’s growing press corps. For the first time, Sicily’s shadiest machinations became a scandal across the whole country.

The first trial took place in the north, in foggy Milan, which was still a political tinderbox following the army massacre of the previous year. Here the ground itself seemed to throb with industry: hydroelectric power, Italy’s ‘white coal’, was cabled in from the Alps; smoke stacks were reaching skywards in the periphery; and a grand stock exchange building was taking shape in the city’s core. Milan was Italy’s shop window to the world. With its strong radical traditions, home of the Socialist Party and its mordant newspaper

Avanti!

, Milan would also turn into the perfect resonance chamber for the Notarbartolo scandal.

Yet when the trial finally opened, only two people were in the dock: the brakeman and the ticket collector on the train where Notarbartolo had been stabbed to death more than six and a half years earlier. General Pelloux would only apply so much leverage on the Palermo judiciary. For the prosecution, the two railwaymen were accomplices to the mafia’s assassins. For the defence, they were, at worst, merely terrified witnesses. For Leopoldo Notarbartolo, they were a chance to spark a publicity firestorm that would finally drive don Raffaele Palizzolo into the open.

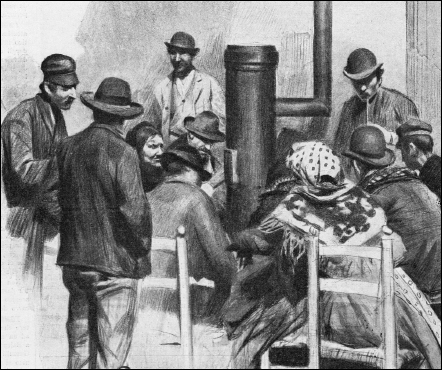

Poor Sicilians summoned to chilly Milan to give evidence in the first Notarbartolo murder trial. Fourteen of them were hospitalized with bronchitis, and one died. A local newspaper took pity on them and arranged a collection.

On 16 November 1899, from the witness stand in Milan, Leopoldo Notarbartolo gave an assured testimony of which his father would have been proud. Speaking briskly in his deep voice, Leopoldo explicitly accused Palizzolo of ordering his father’s murder and then went on to set out everything he had learned about the mafia and the Bank of Sicily. He also cast grave suspicions over the police and magistrates who had never even interviewed Palizzolo about the case.

Calls for Palizzolo to resign began immediately. The political pressure on him intensified day-by-day, until Parliament voted in a special session to remove his immunity from prosecution. The very same evening, Chief of Police Ermanno Sangiorgi enacted the order to arrest him.

Leopoldo Notarbartolo got the publicity firestorm he wanted. The newspapers at home and abroad carried lurid stories about Palizzolo, real or imagined. He seemed like a satirical grotesque come to life. One American resident in Italy, who understandably chose to remain anonymous, claimed to have gained access to one of the open receptions that Palizzolo held every morning at his sumptuous house on Palermo’s main thoroughfare.

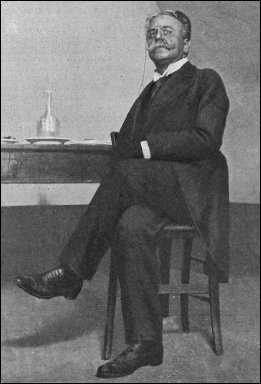

Raffaele Palizzolo, the mafia politician strongly suspected of ordering the Notarbartolo murder. He was photographed only reluctantly, complaining, ‘We have become the object of public curiosity’.

The American visitor explained that Palizzolo’s bed was his throne: its heavy mahogany frame was inlaid with mother of pearl and surmounted by a baldachin; it stood, surrounded by numerous gaudily ornamented spittoons and shaving mirrors on stands, at the centre of a hall hung with pink silks. A crowd of petitioners gathered round about: council commissioners in search of seats on committees, policemen who wanted to win a promotion, and former convicts still sporting their penitentiary crew cuts. One by one, Palizzolo’s major-domo would pick out the supplicants and guide them to a perch on one of the great bed’s broad, upholstered flanks. Palizzolo greeted them all effusively, sitting up in his nightgown, holding a cup of chocolate with one hand and making extravagant gestures with the other.

Palizzolo is a small man with the short, thick neck of a bull and black, shining hair, parted in the middle. Except for his bushy eyebrows, he has few masculine features. His chin is weak and his forehead denotes cunning rather than breadth of thought and strength of character.

The fingers of both his fat, stubby hands were covered with rings—rings of all sorts, marquis, snake and signet rings, set with diamonds, rubies and opals, a whole jeweller’s tray full. Yet under this rather vulgar display, under this half-womanish, half-foppish mask, lies hidden a shrewd personality and a calculating mind of no mean order.