Blood Brotherhoods (97 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

Back in Dalla Chiesa’s apartment in the Prefect’s residence, the General’s safe was opened and emptied of its contents.

Even in Italy, even in the 1980s, shame could carry political weight. Days after the Dalla Chiesa murder, Italy’s two houses of parliament gave an express passage to the anti-mafia legislation that Pio La Torre had been campaigning for: the Rognoni–La Torre law, as it became known.

A hundred and twenty-two years had passed since Italian unification, years when the violence of organised crime had been a constant feature of the country’s history. The mafias’ methods—infiltrating the state and the economy through intimidation and

omertà

—had been familiar to the police throughout. Yet only now had Italy passed legislation tailored to those methods. The delay had been exorbitant. The price in blood had been terrible. Nevertheless, Italy finally had its RICO acts.

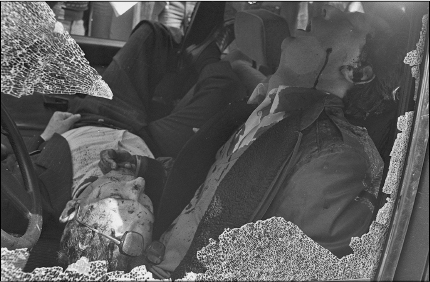

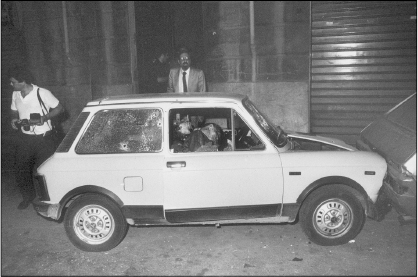

La Torre and his bodyguard were murdered in April 1982. His legacy was the law that underpins the anti-mafia struggle to this day.

‘Here died the hope of all honest Sicilians’. Dalla Chiesa, his wife and bodyguard were machine-gunned to death in September 1982.

The Rognoni–La Torre law had its limits. It explicitly applied ‘to the camorra and the other associations, whatever their local names might be, that pursue aims corresponding to those of mafia-type associations’. The ’ndrangheta, typically, was not deemed worthy of name-dropping. More substantially, there were no measures to regulate the use of mafia penitents passed in the aftermath of the via Carini massacre. Dalla Chiesa had fought Red Brigade terror using penitents who had been incentivised by reductions in their sentences. He wanted the same incentives to apply to

mafiosi

. But, for good reasons and bad, Italy’s political class remained profoundly wary of what mafia penitents might say. If the ongoing bacchanalia of blood-letting within the world of organised crime ever generated any penitents, and if the police and magistrates wanted to use their testimony to test the Rognoni–La Torre law, then improvisation would be the only recourse.

Right on cue, barely a month after the Rognoni–La Torre law entered the statute book, the first penitent arrived. Not from Palermo, however, but from Naples.

Pasquale ‘the Animal’ Barra was the first initiate to the Nuova Camorra Organizzata, its second in command, and the lord high executioner of the

Italian prison system. He was a childhood friend of NCO chief Raffaele Cutolo, and the Professor had dedicated a poem to his knife-fighting skills. In August 1981, on the Professor’s orders, ‘the Animal’ murdered yet another inmate, a Milanese gangster. The victim was stabbed sixty times.

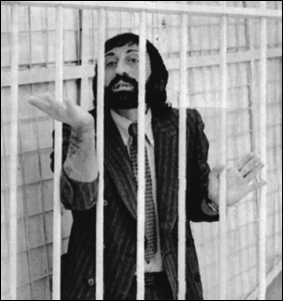

Prison assassin. Pasquale ‘the Animal’ Barra was the Nuova Camorra Organizzata’s principal enforcer within the prison system.

The problem was that the gangster in question also happened to be the illegitimate son of Sicilian-American Man of Honour Frank Coppola. The Professor was called to account by Cosa Nostra for the killing. Fearing an out-and-out confrontation with Palermo, he cut his childhood friend loose: he said that the Animal had murdered Frank Coppola’s son on his own initiative.

The Animal was now an outcast in the prison underworld, persecuted by the affiliates of every mafia, including his own. He shunned all contact with others, always made his own food and drinks, and took to carrying a clasp-knife hidden in his anus at all times. Eventually, the pressure and his sense of betrayal overcame his blood bond to the Cutolo organisation: the Animal begged the authorities for help. He told investigators the whole story of the Nuova Camorra Organizzata, right from its foundation in Poggioreale prison.

With the NCO disintegrating after the Professor was sent to the prison island of Asinara, more defectors soon joined the Animal. On 17 June 1983, magistrates issued warrants for the arrest of no fewer than 856 individuals across Italy, ranging from prisoners and known criminals, to judicial officials, professionals and priests. They were all charged under the Rognoni–La Torre law. Italy’s newest and most important piece of anti-mafia legislation, and the crucial evidence of the penitents, were about to be tried out on the Nuova Camorra Organizzata.

D

OILIES AND DRUGS

A

N EXERCISE BIKE FOR ASTRONAUTS

. A

N ALARM CLOCK CONTRAPTION THAT TIPPED

persistent sleepers out of bed. A drastic cure for the Po valley fog.

A father flown home from Iran to his young family for Christmas. An aged but picky Neapolitan spinster matched with the Spanish flamenco dancer of her dreams.

Talented kids. Fancy dress. Comedy turns. Cheery jazz. Good causes. A set made up to look like a giant patchwork quilt. And a scruffy green parrot that resolutely refused, despite the tricks and blandishments of dozens of studio guests, to squawk its own name: ‘Portobello’.

On Friday nights, between 1977 and 1983, 25 million Italian TV viewers had their cockles warmed and their tears jerked by a human-interest magazine show called, like the parrot,

Portobello

. Many thousands of ordinary people took part in the show: their phone calls were answered by a panel of lip-glossed receptionists who sat at one end of the studio floor. The host of

Portobello

skilfully deployed his patrician manners, common touch and toothy smile to hold it all together with aplomb. His name was Enzo Tortora; he had been born into a well-to-do family in the northern city of Genoa in 1928, and

Portobello

made him one of the three or four most popular TV personalities in the country. Between the cosy, warmhearted Italy that

Portobello

constructed around the clean-living Tortora, and the savage and corrupt world of the Nuova Camorra Organizzata, the distance was astral.

Tortora’s show owed its name to London’s Portobello Road market for antiques and secondhand goods. The core idea was to stage a televised exchange

service for curios. And the idea very quickly caught on. Although RAI, the state broadcaster, sternly told them not to, viewers sent in every conceivable bit of bric-a-brac for barter or auction. The contents of the nation’s attics soon filled up the studio’s huge storage facilities and spilled into the corridors.

Somewhere, lost among those piles of humble treasure, was a package dispatched from Porto Azzurro prison, on the Tuscan island of Elba; it contained eighteen silk doilies, hand-crocheted by a long-term inmate called Domenico Barbaro. Five years later, Barbaro’s doilies triggered one of Italy’s most notorious miscarriages of justice. Because of them,

Portobello

went off the air, and Enzo Tortora was accused of being a cocaine dealer to the stars, and a fully initiated member of Raffaele Cutolo’s Nuova Camorra Organizzata. The world of

Portobello

and the world of organised crime collided. The resulting explosion inflicted grave damage on the Italian judicial system at the very moment when the power of Italy’s mafias was reaching its peak. Just when the Italian state finally had the weapons it needed to combat organised crime, it suffered yet another blow to its legitimacy.

Tortora was arrested before dawn on 17 June 1983, in the luxury Roman hotel that had become a second home. As is so often the case in Italy, fragments of the evidence against him were leaked to the media while he was still being interrogated, creating a widespread assumption that he was guilty. On 21 August—long before any trial—the key testimony against Tortora was published in the current-affairs magazine

L’Espresso

. His principal accuser was another prisoner and

camorrista

, Giovanni Pandico.

Pandico was that rare thing, a con who could read and write; he even had a smattering of legal knowledge, which was enough to make him a Clarence Darrow in the eyes of his fellow jailbirds. His appearance also proclaimed his intellectual gravitas: bland, waxy features hidden behind the boxy black frames of his spectacles. But Pandico was also unstable and very violent. Even as a young man, psychiatrists had defined him as paranoid, and as having an ‘aggressive personality strongly influenced by delusions of grandeur’. In 1970, Pandico was released from a short sentence for theft. Someone had to be responsible for his troubles with the law, and that someone had to be important—like the local mayor. As his paranoid reasoning dictated, Pandico rampaged through the Town Hall, Beretta 9mm in hand, killing two people and wounding two others. The mayor only saved himself by tipping over his desk and sheltering behind it.