Blood Brotherhoods (30 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

The rise of the picciotteria brutally exposed the fragmentation of Calabria’s ruling class. At war with one another over local politics and land, the Calabrian social elite proved utterly incapable of treating the newly assertive criminal brotherhood as a common enemy. In Africo, some men of education and property testified against the

picciotti

, and were duly threatened to the music of the

zampogna

. Others, like Giuseppe Callea, were more than happy to ally themselves with the gang. But it would be naïve of us to think that such cases saw good citizens pitted against shady protectors of gangsters. Legality and crime were not what divided Calabrians; ideology of one colour or another was not what brought them together. On Aspromonte, family, friends and favours were the only cause of conflict, and the only social glue. The law, such as it was, was just one more weapon in the struggle. The few sociologists who took an interest in Calabria after Italian unification noted that the propertied class ‘lacked a sense of legality’, and even ‘lacked moral sense’. Whatever terms one used to describe it, the rise of the picciotteria showed that the lack was now infecting the other social classes.

Despite this proliferation of organised criminal activity, the prosecution of the early ’ndrangheta in Africo was a success, in the very short term. The butchers of Maviglia were convicted, as were dozens and dozens of the

picciotti

. Across southern Calabria the police and

Carabinieri

registered similar results, and would continue to do so for years to come. But the struggle to assert the state’s right to rule was close to futile from the start. The Lads convicted of ‘associating for delinquency’ served their risibly short sentences in the very same jails where they had learned their Attitude in the first place.

And there was no sign of an end to the fundamental weaknesses in Calabrian society that gave them their foothold outside the prisons.

The criminal emergency in Calabria utterly failed to capture the attention of national public opinion. All too few Italians were prepared to ‘look through the microscope at the little causes that make little hearts beat’. In the long term, Italy would pay the price for this collective failure of the imagination. Nothing that happened to Calabrian shepherds and peasants could ever be news. Nothing that is, until the exploits of a woodsman called Giuseppe Musolino turned him into the Brigand Musolino, the ‘King of Aspromonte’, and perhaps the greatest criminal legend in Italian history.

T

HE

K

ING OF

A

SPROMONTE

T

HE FACTS OF

G

IUSEPPE

M

USOLINO

’

S LIFE WOULD COUNT FOR LITTLE

,

IN THE END

. B

UT

the facts are nonetheless where we must begin.

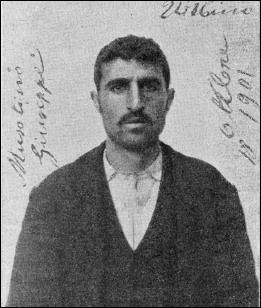

Musolino was born on 24 September 1876 at Santo Stefano in Aspromonte, a village of some 2,500 inhabitants situated 700 metres up into forests overlooking the Straits of Messina. His father was a woodsman and a small-time timber dealer just successful enough to set himself up as the owner of a tavern. Musolino grew into a woodsman too. But it was the violent tendencies of his youth that would most attract the attention of later biographers: before his twentieth birthday he got into trouble several times for weapons offences and for threatening and wounding women.

The Musolino saga really began on 27 October 1897, in his father’s tavern, when he became involved in an argument with another young man by the name of Vincenzo Zoccali. The two arranged to have a fight and Musolino suffered a badly cut right hand. Musolino’s cousin then fired two shots at Zoccali, but missed.

Two days later, before dawn, Zoccali was harnessing his mule when someone shot at him from behind a wall. Again the bullets failed to find their target. Musolino, whose rifle and beret were found at the scene, went on the run in the wilds of Aspromonte. He was recaptured just over five months later, and in September 1898 he was given a harsh twenty-one-year sentence for attempted murder. Enraged at the verdict and proclaiming himself the innocent victim of a plot, Musolino swore vendetta. He would eat Zoccali’s liver, he cried out from the dock.

Giuseppe Musolino, the ‘King of Aspromonte’.

On the night of 9 January 1899 Musolino and three other inmates, including his cousin, escaped from prison in Gerace by hacking a hole in the wall with an iron bar and lowering themselves to the ground with a rope made from knotted bedsheets. The promised vendetta began on the night of 28 January, when Musolino gunned down Francesca Sidari, the wife of one of the witnesses against him. He apparently mistook her for his real target as she stooped over a charcoal mound. When the gunshots and screaming attracted the attention of her husband and another man, Musolino shot them too. He left them for dead, and fled once more into the mountains.

The Brigand Musolino (as he soon became known) now entered a twin spiral of vengeance: his targets were both the witnesses against him in the Zoccali case and the informers recruited by the police in their efforts to catch him.

A month after his first murder, Musolino killed again, stabbing a shepherd whom he suspected of being a police spy. In mid-May the bandit returned to Santo Stefano and caught up with Vincenzo Zoccali—the man whose liver he had vowed to eat. He planted dynamite in the walls of the house where Zoccali was sleeping with his brother and parents; but the charge failed to detonate. (The family subsequently fled to the province of Catanzaro.) Musolino badly wounded another enemy a few days later.

The sequence of attacks continued through the summer of 1899. In July he killed one suspected informer with a single shotgun blast to the head. A week later he shot another in the buttocks.

In August the brigand went all the way to the province of Catanzaro in pursuit of Vincenzo Zoccali and his family and succeeded in killing Zoccali’s brother. He then returned quickly to a village just below Santo Stefano where he murdered another man he may have suspected of being an informer.

Musolino then vanished for six months.

The next the world heard of Musolino was in February 1900 when he reappeared on Aspromonte with two young accomplices; he shot and wounded his own cousin by mistake. The brigand apparently kneeled before his bleeding cousin, offered him his rifle, and begged him to take vengeance for the error there and then. The request was declined and the brigand continued with his attacks.

Musolino found his next prey in the Grecanico-speaking village of Roccaforte, blasting him in the legs with a shotgun. The prostrate victim then managed to convince the bandit that he was not, as suspected, a police spy. Musolino tended the man’s wounds for half an hour and then sent a passing shepherd to fetch help.

On 9 March 1900 one of Musolino’s accomplices, a man from Africo called Antonio Princi, betrayed him to the police. As part of the plan to capture Musolino, Princi left some

maccheroni

laced with opium in the bandit’s hideout, which at the time was in a cave near Africo cemetery. Princi then went to get the police. Five policemen and two

Carabinieri

followed him back to the hideout. But the opium had been sitting on the shelf of a local pharmacy for so long that it had lost much of its narcotic power. Even after eating the

maccheroni

, Musolino still had sufficient command of his faculties to fire at his would-be captors and then escape across the mountain, with the police and

Carabinieri

in pursuit.

In the early hours of the following morning Musolino was surprised while urinating by Pietro Ritrovato, one of the two

Carabinieri

; the brigand fired first from close range. The young

Carabiniere

suffered a gaping wound in his groin, and died in torment several hours later.

After another six months of silence Musolino and another two accomplices killed again on 27 August 1900. They chased their victim, Francesco Marte, onto the threshing floor of his own house, where he stopped, turned and begged them to be allowed the time to make his peace with God before dying. They allowed him to kneel down, and then shot him repeatedly in front of his mother, continuing to fire even when he was already dead. Musolino would claim that Marte was a traitor who was involved in the

maccheroni

plot against him.

Subsequently the same two accomplices, perhaps acting on his behalf, also tried and failed to kill the former mayor of Santo Stefano who had testified when Musolino went on trial for attempted murder.

The brigand’s last violent attack came on 22 September 1900, when he wounded yet another alleged informer in Santo Stefano.

Musolino’s bloody rampage and the continuing failure to arrest him had long since become a political scandal. The Aspromonte woodsman was discussed in parliament. The government’s credibility was at stake. Hundreds of uniformed men were sent to southern Calabria to join the hunt. Yet still, for another year and more, Musolino would manage to evade them all . . .

There is one more important fact about Musolino: he was a Lad with Attitude.

At the height of the political furore over the brigand, Italy’s most valiant journalist, Adolfo Rossi, took the very rare step of actually going down to Calabria to find out what was going on. From police and magistrates he learned all there was to know about the new mafia.

Rossi toured the prisons and saw the

picciotti

in their grey- and tobacco-striped prison uniforms. He went to Palmi, which he learned was ‘the Calabrian district where the picciotteria was strongest’. Palmi’s Deputy Prefect glumly explained that, ‘one trial for “associating for delinquency” has not even finished by the time we have to start preparing the next one’.

Rossi visited Santo Stefano, Musolino’s home village, and even climbed all the way up to Africo. He was shocked by the squalor he found there, writing that ‘the cabins are not houses being used as pig sties, but pig sties used as houses for humans’. The

Carabinieri

told him how, a few years earlier, members of the sect had ‘cut a man to pieces, and then put salt on him like you do with pork’.

Adolfo Rossi’s long series of reports from Calabria is still the best thing ever written about the early ’ndrangheta; it deserved to be read far more widely than in the local Venetian newspaper in which it appeared. And everyone Rossi interviewed agreed that Musolino was an oathed member of the picciotteria—albeit that opinions varied on when exactly Musolino was oathed, and what rank he held. Rossi saw reports that showed how the

Carabinieri

in Santo Stefano had Musolino down for a gangster from the beginning. On the day after Musolino’s first knife fight with Vincenzo Zoccali, they wrote that he belonged to the ‘so-called maffia’.

While Musolino was in custody awaiting trial for attempted murder, the jailers observed him behaving like a

camorrista

. One guard stated to Rossi that

Musolino entered this prison on 8 April 1898. Later some of his cellmates informed me that in June of the same year he was elected a

camorrista

[i.e., a senior member of the Society].

In Africo Rossi spoke to a police commander who explained that Musolino had avoided capture for so long because he had the support of the picciotteria network across Aspromonte and beyond. One man who confessed to Rossi that he had sheltered Musolino was the mayor of Africo, a shady figure who testified

against

the picciotteria back in 1894. In Santo Stefano, Rossi learned that some of the brigand’s accomplices were Lads, and that some of his escapades, including his original spat with Vincenzo Zoccali, had more to do with the internal politics of the mob than with his personal programme of vengeance.

Despite these facts Musolino became a hero: a wronged avenger, a solitary knight of the forest, a Robin Hood, the ‘King of Aspromonte’.

His fame began to grow rapidly after his prison breakout in 1899. It was a local phenomenon at first. Most people on Aspromonte firmly believed that Musolino was innocent of the charge for which he was originally imprisoned—that of attempting to murder Vincenzo Zoccali. And, in truth, there are one or two residual doubts about how sound the conviction was. Musolino’s ‘innocence’, genuine or not, proved to be the seed of his fame. The peasants of Aspromonte, ignorant and pitiably poor, regarded the state with inborn suspicion. For such people, in such circumstances, a renegade hero who only killed false witnesses was all too captivating a delusion.

Musolino found food and shelter everywhere he went on Aspromonte. For his sake, women kept lanterns lit for the Madonna of Polsi and for Saint Joseph (San Giuseppe, the patron saint of woodworkers, from whom Musolino took his Christian name). Much of this support was managed by the picciotteria. Much of it can be explained by perfectly understandable fear. Some of it—and it is impossible to tell just how much—was down to the brigand’s burgeoning popular aura.