Blood Brotherhoods (38 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

Senator Saredo did not give any evidence to back up his use of the phrase ‘high camorra’. His inquiry found no trail of blood or money leading from the upper world of politics down into the underworld where the camorra, in the strict sense, operated. In fact the low camorra remained a mere peripheral blur in Saredo’s field of vision.

Saredo’s provocative language was therefore misleading, but understandable. Ever since Italy had found out about the criminal sect called the camorra, it had also used ‘camorra’ in a much vaguer way, as an insult. The c-word was a label for any shady clique or faction—for

other people

’s cliques or factions. As the nineteenth century drew to a close, this term of abuse was steeped in new bile. Italians were growing bitterly frustrated with the way their politics worked. The mysterious deal brokering, the jobbery, the strong-arm tactics: ‘camorra’, it sometimes seemed, was everywhere in the country’s institutional life. A hostility towards politics—

antipolitica

as it is sometimes called—has been a constant feature of Italian society ever since. With his talk of a ‘high camorra’, the old law professor showed that he had a mischievous streak: he was knowingly appealing to what was by now a conditioned reflex in public opinion.

As soon as it became clear that the Saredo inquiry was doing its job seriously, some leading politicians began briefing against it: what Saredo had termed the ‘high camorra’ was mobilising to defend itself. Tame journalists heaped abuse on Senator Saredo. Knowing the threat posed by a wave of ‘antipolitics’, they appealed to another conditioned reflex of Italian collective life: a suspicious, defensive local pride. So the northerner Saredo had besmirched the image of Naples, the editorials wailed. There may have been a few cases of corruption. But that was because Naples was poor and backward. What the city needed was not haughty lectures, but more money from government. Lots more.

In Italy, public indignation has a short half-life. When it fails to catalyse change, it steadily decays into less volatile states of mind: fatigue, forgetting, and sullen indifference. By 1904 the indignation about political corruption and organised crime that marked the turn of the century had all but totally degenerated. Raffaele Palizzolo was finally acquitted of ordering the murder of banker Emanuele Notarbartolo in July of that year. In Naples too, the Casale trial and the Saredo inquiry no longer provoked the same anger. The Socialist Party, having tried to ride the scandals, was now divided and discredited by a failed general strike. The chiefs of the ‘high camorra’ could now go on the offensive.

The Prime Minister of the day was Giovanni Giolitti—

the

dominant figure in Italian politics between the turn of the century and the First World

War. Giolitti was a master of parliamentary tactics, better than anyone else at the devious game of coaxing factions into coalitions.

In the early 1900s Giolitti presided over an unprecedented period of economic growth and introduced some very welcome social reforms. But his cynicism made him as loathed as he was indispensable. ‘For your enemies, you apply the law. For your friends, you interpret it’, Giolitti once said: a manifesto for undermining public trust in the institutions, and all too accurate an encapsulation of the pervading values within the Italian state. He also compared governing Italy to the job of making a suit of clothes for a hunch-back. It was pointless for a tailor to try and correct the hunchback’s bodily deformities, he explained. Better just to make a deformed suit. Italy’s biggest deformity was of course organised crime, and Giolitti showed himself to be as expedient as any previous statesman in tailoring his policies around it. One later critic, incensed at the way the Prefects used thugs to influence elections in the south, called Giolitti ‘the Minister of the Underworld’.

In the general election of November 1904, Giolitti (whose lieutenants in Naples had orchestrated the drive to undermine the Saredo inquiry’s authority) deployed all the dark arts of the Interior Ministry to turn the vote. In Vicaria, the constituency in Naples that had elected a Socialist MP in 1900,

camorristi

—real

low camorristi

—were enlisted to bully Socialist supporters. On polling day, alongside the police, gangsters stood guard outside the places where votes were changing hands for government cash.

Someone deep within police headquarters that day was endowed with a cynical historical wit. For

camorristi

who enjoyed official approval were given tricolour cockades to wear in their hats. So, just as they had done in the days before Garibaldi’s Neapolitan triumph in 1860,

camorristi

in patriotic red, white and green favours formed a flagrant alliance with the police. The traditional trade in promises and favours between the ‘low camorra’ and the ‘high camorra’ had resumed. Nothing, it seemed, had changed.

Barely eighteen months later, things changed more dramatically than they had done at any point in the camorra’s history.

Among the

camorristi

in tricolour cockades on election day in 1904 was the boss of the Vicaria chapter of the Honoured Society, Enrico Alfano, known as Erricone—‘Big ’Enry’. In the summer of 1906, Big ’Enry became caught up in what the

New York Times

would call ‘the greatest criminal trial of the age’.

The Cuocolo trial, as it was known, was the stuff of a newspaperman’s dreams. Tales of a secret sect risen from the brothels and taverns of the slums to infiltrate the salons and clubs of the elite. Police corruption and political malpractice. A cast of heroic

Carabinieri

, villainous gangsters,

histrionic lawyers and even a camorra priest. The drama that unfolded in Viterbo seemed to have been fashioned expressly for the new media age. Foreign correspondents, news agencies, and the fibrillating images of Pathé’s

Gazette

could now relay the excitement to every corner of the globe. Nor was the Cuocolo trial just a media event: unlike the Notarbartolo affair, it was a turning point in the history of organised crime. Not only did it reignite the political controversy and emotion that the Saredo inquiry had generated. Not only did it threaten, once more, to expose the sordid deals between

camorristi

and politicians. It actually killed off the camorra. With the Cuocolo case, the secret sect known as the camorra ceased to exist. Big ’Enry was to be the last supreme boss of the Honoured Society in Naples. And it all began with the discovery of two bodies.

T

HE CAMORRA IN STRAW-YELLOW GLOVES

J

UST BEFORE

9

A

.

M

.

ON

6 J

UNE

1906

POLICE ENTERED AN APARTMENT IN VIA

Nardones, central Naples. They found the occupant, a former prostitute called Maria Cutinelli, on a bed soaked in blood; she was in her nightshirt and had died of multiple stab wounds—thirteen in total—to her chest, stomach, thighs and genitals. The police suspected a crime of passion and immediately began looking for the victim’s husband, Gennaro Cuocolo. (Like most Italian women then as now, Maria Cutinelli had kept her maiden name.)

The hunt was over before it began. News soon arrived from Torre del Greco, a settlement squeezed between Mount Vesuvius and the sea some fifteen kilometres from the city: Gennaro Cuocolo had been found dead at dawn. His body lay in a lane that ran along the coast behind the slaughterhouse. He had been stabbed forty-seven times and his skull had been smashed with a club. Much of Torre del Greco was still smothered in ash from a recent volcanic eruption. Traces of a struggle in the black-grey carpet allowed Cuocolo’s last seconds to be outlined: there were several attackers; after killing their victim, they lugged the body onto a low wall overlooking the sea—as if to put it on display. Cuocolo’s blood mingled with the gore seeping through a gutter that ran from the slaughterhouse onto the crags.

There were good grounds for guessing the real motive for the murders. Cuocolo made his living commissioning burglaries and fencing the resulting booty. He was notoriously enmeshed with organised crime—a former

member of the Honoured Society in the Stella quarter, in fact. The conclusion was surely plain: the camorra killed the Cuocolo couple.

The chief suspects were soon identified. At the same time that Gennaro Cuocolo was being stabbed and bludgeoned to death, five men were eating a leisurely dinner of roasted eel at Mimì a Mare, a picturesque trattoria only a couple of hundred metres from the murder scene. The five were arrested: at least three of them were known gangsters, including Big ’Enry who, as the police were well aware, was the effective supreme boss of the Honoured Society.

Yet initial investigations failed to unearth anything concrete to connect the diners at Mimì a Mare with the carnage behind the slaughterhouse. None of the five had left the dinner table long enough to kill Cuocolo. Big ’Enry and his friends walked free, much to the outrage of the Neapolitan public.

The decisive breakthrough came only at the beginning of the following year, as a result of the longstanding rivalry between the two branches of Italian policing. The

Pubblica Sicurezza

, or ordinary police force, was run from the Ministry of the Interior. The

Carabinieri

, or military police, operated under the Ministry of War. In theory the two forces patrolled different areas: the police were based in the towns and cities and the

Carabinieri

in the countryside. In practice, their duties often overlapped. The Cuocolo investigation was to be a classic case of the tensions and turf wars that often resulted.

In 1907, the

Carabinieri

wrested control of the Cuocolo murder probe from the police, and soon submitted a startling testimony by an informer: he was a young horse trader, groom, habitual thief, and

camorrista

called Gennaro Abbatemaggio.

Gennaro Abbatemaggio made history when he broke the code of

omertà

. He recounted every detail of the Cuocolo murders: motive, plan and execution. But his evidence was far more important than that. There had never been a witness like him. Of course plenty of gangsters had spoken to the authorities before, and plenty of trials had drawn on evidence from deep within the Sicilian mafia, the Neapolitan camorra, and the Calabrian picciotteria. But no one before Gennaro Abbatemaggio had stood up in court to denounce a whole sect. Before him, no self-confessed mobster had made his own life and psychology into an object of public fascination and forensic scrutiny. Gennaro Abbatemaggio would become the biggest of the many celebrities created by the Cuocolo affair.

Abbatemaggio explained to the

Carabinieri

that the murder victim, Gennaro Cuocolo, first became the target of the camorra’s anger because he broke its most sacred rule by talking to the authorities. Cuocolo’s breach of

omertà

came after he commissioned a burglary by one Luigi Arena. In order to keep all the loot, Cuocolo betrayed his partner in crime to the police.

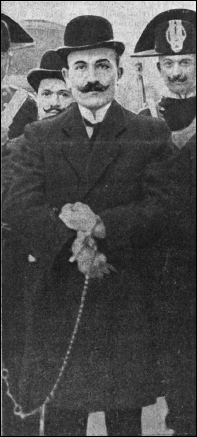

Enrico Alfano, or ‘Erricone’ (Big ’Enry), the camorra’s dominant boss.

The hapless thief Arena was sent to a penal colony on the island of Lampedusa, situated between Sicily and the North African coast. From there, smarting with understandable rage, he wrote two letters to a senior

camorrista

to demand justice.

The thief’s plea for vendetta was debated at a camorra tribunal, a meeting of the entire leadership of the Honoured Society, which took place in a trattoria in Bagnoli in late May 1906. The tribunal sentenced Cuocolo to death and ruled that his wife, who knew many of his secrets, should die too. Big ’Enry, boss of the Vicaria quarter and the most authoritative

camorrista

in the city, took on the job of organising the executions. He nominated six killers, in two teams, to do away with Cuocolo and his wife. Big ’Enry also set up the eel dinner in Torre del Greco so that he could keep an eye on the gruesome proceedings.

So Abbatemaggio asserted. He also said he knew all of this because he had served as a messenger to Big ’Enry in the build-up to the Cuocolo slayings. He also claimed to have been present, both when the death squads were debriefed by their boss, and when the

camorristi

shared out the jewellery stolen from Maria Cutinelli’s blood-spattered bedroom.

There was a subplot to Abbatemaggio’s narrative, a subplot that would become the most loudly disputed of his many claims. He said that Gennaro Cuocolo always wore a pinkie ring engraved with his initials. Cuocolo’s killers were supposed to have pulled the ring from his dead hand and sent it to the penal colony of Lampedusa as proof that camorra justice had been done. However, said Abbatemaggio, one of the killers disobeyed orders and kept the trinket for himself. Many months later, when

Carabinieri

following Abbatemaggio’s tip-off raided the house where the killer lived, they slit open his mattress and out fell a small ring bearing the initials G.C. Here was crucial material corroboration of the stool pigeon’s testimony.