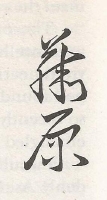

Blood and Chrysanthemums (16 page)

A DREAM OF DEATH

There is fire. I feel its heat, sweeping up behind me in the narrow tunnel along which I run. I know in a moment that it will catch me. Then my blood will boil, my bones melt, my skin blacken and dissolve. When it has passed, there will be no ash, no soot. There will be no sign that I have ever existed. In the second before it reaches me, I scream.

I awoke.

For a moment, I was not certain where I was. My body rocked unsteadily in the darkness. For a moment, I thought I was at sea and almost panicked. Then I remembered. I was in my palanquin on the road north from Edo to my estate.

I extended my senses and brushed the awareness of those around me. From their shadowy thoughts, I could tell that it was twilight. The sun was dipping beyond the mountains to the west, the shadows were long and welcoming. I could safely draw back the heavily lined brocade curtains that sheltered me and step out to survey the night.

But I stayed where I was. I did not need to see to know what our procession looked like: mounted samurai riding front and rear, soldiers marching after and before, bearers bent beneath the weight of their burdens.

Twice a year, the procession travelled this road. In spring, to Edo. In autumn, back to the estate. The shogun trusted the northern lords more in the winter, when the snow closed our mountain passes and kept our armies locked within our own lands. In summer, he preferred that we were at his court, far from our castles and men.

In truth, it should be a relief to return to my own four walls. Edo was dangerous for me. There were spies everywhere and my peculiarities were harder to conceal. I let it be believed that I was a scholar of the more esoteric Buddhist beliefs and so often fasted and preserved my seed as part of my studies. Yet I was careful to never appear to have gained any secret wisdom, any useful insights lest the shogun decide I was either a threat or a tool. One walked a very narrow line between the two dangers—too much power could damn a man, too little destroy him just as easily.

Yet this time I left the city with as much regret as a new bridegroom leaves his marriage bed . . . for this time, I left her.

Bridegroom I was, for the first time in many years. I avoided marriages when I could but it was not always possible. Alliances were required, appearances had to be kept. Wives of mine were either early widows as I falsified my own death . . . or died young themselves.

So when Harada Okisata had offered his daughter I reluctantly took her, though it was in name only, for during the long winter we were both locked by ice and edict on our separate estates. With the spring, I had come to Edo and claimed Tomoe as my wife.

In the darkness, I closed my eyes and thought of her.

The wedding rituals were done, the guests were gone. I had been through this moment more times than I cared to count and yet I dreaded it. I could not help but remember taking my second wife, when I was mortal. It had been so much simpler then. There were politics involved of course, hidden behind the conventions of love and seduction. I sent my wife-to-be poems, as she did in return, inviting me to her bed. I crept to her chambers like a secret lover, though the whole household knew that I was there. In the dark, we suited each other well enough that our poetry the next morning was encouraging. On the morning of our third night together, I did not have to go home before dawn. There was a minor ceremony and we were wed.

This wedding night, I had managed to gain some measure of privacy by having my steward, another Tadeo, banish the scandalized servants to the far wing of the house for this one evening. This strange desire for privacy would be added to my list of eccentricities. Only my new wife’s maids remained, to dress her in the gifts I had sent.

How would she take my revelations, I wondered, this young woman I had seen for the first time at our wedding. There had been those among my wives who were secretly pleased that I did not demand my conjugal rites and those who hated it. All of them were upset that I would not give them the sons they wanted, to seal their positions and ease their hearts. With some of them I had reached an accommodation: I had their blood and their silence, they had my name and my wealth. Others, I dared not trust. Once in a while I still burn incense for their souls, which I sent so early into whatever waited beyond this life.

Then I reached her room. It seemed that in moments we were alone, her maids and Tadeo gone. She knelt in the centre of the room, dressed in the kimono I had given her. “Husband,” she said softly, bowing. “Thank you for your gift to this unworthy one.”

“Stand up and let me see.” She rose with a peculiar kind of grace. There was nothing delicate in her movements but instead a sturdy ease that intrigued me. The kimono was violet silk, woven with a pattern of cranes, the symbol of long life. She lifted her head a little. She was not beautiful and yet . . . “It becomes you.” She nodded acknowledgement of the compliment. I saw her fingers stroke the silk then flicker to touch the ivory carving that adorned her sash.

I presented her with the other gifts I had brought: a small lacquered box holding wooden combs inlaid with gold wisteria patterns, the old symbol of my family. She thanked me for them with the correct measure of decorous pleasure but I noticed that she touched them as she had the silk, her fingertips lingering over the curves and textures.

She served sake and we sat in silence for a few moments. I looked at her bent head, at the sweet, vulnerable curve of the nape of her neck. “There is something I must tell you,” I began at last. “We will speak of it this night and never again, understand? You will never speak of it to anyone else or I will order you to kill yourself. I will ensure that everyone knows that you dishonoured your family’s name.”

“Yes, my lord.”

“I am not like other men. I am impotent.” There was a long silence.

“Were you hurt, my lord? Or is it to do with your studies?” She saw surprise on my face. “Forgive my questions. My father told me you are a learned man, very like a monk or a priest.”

“Yes, it has to do with my studies.” It was not completely a lie. “I cannot give you children but if you obey me I will treat you with honour.”

“Whatever you say, my lord.” She bowed again and then I saw her eyes flicker up to touch my face. “Do you have any . . . needs?”

“None that I cannot satisfy elsewhere.” There was plenty of blood to be had in Edo. I rarely killed, simply took from sleeping servants or townspeople I lulled into forgetfulness. If I wished more than blood, there were the courtesans of the floating world.

“I am your wife. If you find me unsatisfactory, you must go to another. But please, husband, do me the honour of allowing me to try to please you.”

“You would do that?”

“Of course.” She lowered her head again and I realized that she was afraid of what I might ask of her but determined not to change her mind. I could always take the memory of what I did from her, I told myself. And if it went well . . . but I would not think of that.

“Take off the kimono and go to the bed,” I said at last. I watched her hands as she unwrapped her sash and let the garment fall from her body. They did not shake. She pulled the pins from her hair and it tumbled down like a black river. Her body glowed through the gossamer silk of her last garment. When I turned back from extinguishing the lamps, she was sitting in the centre of the mat.

She looked calm and composed, but when I touched her she was trembling. The hand I took in mine was cold. It convulsed automatically, curling into a fist as my fingers slipped down around her wrist. We sat in silence for a moment, my thumb stroking the pulse that quickened beneath her skin. Her head bent, she seemed to watch the movement with an odd, almost fierce, concentration. One by one her fingers relaxed, unfurling like a white, five-petalled flower. When I kissed the centre of her palm, I heard her sigh.

Much later in the night she shook again, but this time it was in pleasure. When I put my mouth against her throat, she was still for a long, frozen moment. I heard her breath catch and, through the sweet fever of her blood, felt a touch of cold despair. Then she gave a ragged sigh and tightened her arms around me, holding me against her.

She was drowsing when I bent over to whisper the words of forgetfulness in her ear. She stirred and woke. “What . . . ?”

“Go back to sleep.”

She turned into my arms and smiled sleepily. “Did I please you?”

“Yes.”

“You will not go to anyone else?”

“Tomoe,” I began, then stopped as she put her hand up to her mouth. Her curious fingers touched my teeth.

“I will never speak of what we do,” she said seriously. “I will not complain if you go to another. But I would be honoured if you would come to me. I would be happy if you would come to me.” Then she kissed me.

She was no beauty but there was beauty in her just the same, as I discovered at that moment and in a thousand moments after. Her mouth was too large but smiled with heartbreaking purity. Her eyes were too narrow but saw everything. Her face was too sharp but there was strength in it, beneath the paint and pretence. Her body was too lush, too curved, as undeniable in its physical presence as stone or wood. There was beauty even in her love of beauty. Hers was not a poet’s appreciation of the world but something much more concrete. She revelled in touch and scent and sound more than anyone I had ever known.

By Confucian law, she was mine. By samurai code, she was mine. But from the moment she had kissed me, knowing what I required of her, I was hers.

For a season, we had been together. Now I left her behind in my mansion, guarded by a regiment of soldiers.

In all the years of my unnatural life, I had never thought of trying to create another like myself to share it with me. For many years, I was not even certain how it might be done. But now my mind was full of plans. I would wait awhile before sharing my blood with Tomoe, for she was very young yet. There were things she would want. A child, for instance. An heir, a son . . . a thing I had never dreamed that I might have . . . or even want. I could not give Tomoe one from my own body but something could be arranged. If we hurried, she could raise the child as a mortal woman, then both of them could join me. . . .

There was a sudden cry, terrible and choking, then the palanquin pitched forward. I struggled in a tangle of silk and curtains then scrambled to freedom, my sword in my hand. I emerged into battle; arrows hissing through the twilight, my lieutenant shouting orders, the screams of the dying bearer.

Beyond the line of soldiers who surrounded my palanquin, I could see the bandits who had attacked us. Grubby and ragged they might be, but their swords looked sharp and their archers were good marksmen, I realized, as a soldier to my left cried out and staggered, an arrow jutting out from his throat. Another man stepped in to fill his place and our own archers returned fire, aiming at the thin line of bandits and into the trees beyond them, where their archers crouched.

It would be a battle of attrition and whoever could stand to lose the most men would triumph. They could keep us pinned here much more easily than we could chase them away. My lieutenant materialized at my elbow. “Take my mount, Lord Sadamori. You and the other horseman can be beyond this battle in a moment. We shall hold the bandits here while you escape.”

I shook my head automatically, my eye suddenly caught by a figure moving among the trees. “Not yet, Naomasa,” I said, watching the man move. Hidden he might be to mortal eyes, but I could see him clearly. He had the garb of a bandit but the walk of a swordsman. He was no groundling soldier turned to thievery, no desperate farmer trading rice for robbery. He was a

ronin

, a rogue samurai.

I lifted my sword over my head and raised my voice above the clamour of the battle. “Hail, Lord Bandit. Why not come from the shadows and show yourself?” Behind me, I heard Naomasa hissing orders, heard the patter of feet as soldiers scurried to convey them down the line. The archers held their arrows in their bows. The bandits paused as well, the undisciplined letting their eyes drift towards the shadow in the forest.

After a moment, he emerged. He was very dark; bearded face, ragged topknot, black kimono. Only his sword gleamed like liquid silver. I stepped forward, to the edge of my shield of warriors. “Good evening.” He nodded briefly but said nothing. “You waste men and effort, Lord Bandit.”

“Perhaps it is you who do so. Surrender your wealth now and I will let you pass.”

“Why should I surrender what you cannot take without great loss? Should I value my goods so lightly?”

“Should you value your life so lightly, my lord?”

“Be assured I set great value on my life. That is why I propose an alternative solution. You and I will fight. If I win, my party passes by unhindered. If you win, my goods and men are yours.”

There was a long silence. I knew he weighed the options in his mind but it was inevitable that he would accept. To do otherwise would suggest that he was afraid of me and that no samurai, rogue or otherwise, would ever do.