Blood and Chrysanthemums (11 page)

Were we to make

A thousand autumn nights

Into one,

There would still be things to say

At cockcrow.

—Tales of Ise

THE LADY OF THE AUTUMN MOON

As the chrysanthemums bloomed and the leaves began to turn and fall, a certain young man was forced to leave the capital. His father and his uncle had long been in competition for the honours of the court and now, with the announcement of his uncle’s daughter’s engagement to the crown prince, it was apparent who had been victorious. The young man’s father found himself without power, and the uncle, to rid himself of the young rival, named the young man to the governance of a distant province.

The family lamented but there was nothing to be done. Though the omens were inauspicious for such a journey, the uncle insisted that it must occur immediately, and the young man could not refuse. Accompanied by four retainers, he left his weeping wives (who mourned but did not volunteer to follow him into exile, perhaps, to be charitable, in hopes that it would not be permanent) bid farewell to his father, and began the journey on horseback to his new home, far to the northwest.

Along the way, ill luck befell them and the small group was beset by bandits. They fought valiantly but to no avail. The retainers were slain, the horses and their burdens stolen, and the young man barely escaped. Beaten and bruised, he stumbled through the wild woods, hopelessly lost among the pine trees. His heart was filled with terror, for this wild mountain land was long known to be home to ghosts and demons such as the malicious long-nosed

tengu

.

So it was that when he saw a faint light among the trees, he staggered towards it, praying that it would prove to be the retreat of a hermit monk or some other kind of person who would take him in and shelter him. Instead, when he emerged from the darkness of the trees, he saw a fine house beneath the moonlight. Soft lamplight glowed from an open doorway.

Thanking the gods for his good fortune, he rushed to the house and mounted the veranda. As his step sounded on the wood, a figure appeared in the doorway. In the lamplight, he could see that it was an old woman, clad in old-fashioned servant’s garb, her long, grey hair streaming about her shoulders as if she had just risen from her bed.

The young man realized for the first time what a sight he himself must be. His travel clothing, which had been fine and elegant when he left Heian-kyo, was now torn and stained. He had lost his hat in the woods and there were dead leaves and twigs in his hair. All his belongings, except for one pouch which contained the scrolls concerning his new position, had vanished with the bandits.

He bowed low and spoke in his most courteous fashion. “Forgive my intrusion. I and my retainers were set upon by bandits on the road. All of my companions were killed and I barely escaped with my life. I beg you to allow me the shelter of your house.”

When he finished speaking, she knelt on the floor and bowed low, for his aristocratic origin was evident in his speech. “Please be welcome in our humble house, my lord. If you will enter, we will do our best to serve you.”

Her greeting was so sincere and welcoming that he almost fell into the house but managed to keep his feet and follow her through the shadowy corridors until they reached a garden. In the moonlight, the young man could see the heavy, overhanging boughs of trees and ragged, uncut sagebrush and grass. In the air there was a sharp, metallic scent, and in one corner steam rose from a circle of rocks. “Our spring has healing waters, so they say. If you wish to bathe, I will bring you clean clothing and then take you to the lady.”

This sparked the young man’s curiosity, but the thought of the hot water drew him more and he spared no time for questions. He bathed in the spring, whose hot water did indeed seem to rejuvenate him, and then dressed in the clothing the old woman brought for him. They were of fine quality but the style was old-fashioned as the old woman’s and he had to settle for combing back his wet hair as he had no way to re-dress it in proper court fashion.

As he followed the woman back to the house, he decided it must be the home of some old aristocratic family, who had left the capital some years before to live in this strange isolation. Perhaps they had been victims of a struggle for power, as he had been.

The woman led him through a veil of silken panels into a dimly lit room. She gestured for him to be seated on a padded pillow then knelt to pour heated wine into a saucer. He gratefully swallowed the first and, when offered, the second saucer as well.

Then the old woman bowed to him again, rose and padded to the doorway. Alone, the young man looked about the room and saw for the first time the thin screen set across on end. Beneath it, he could see the flow of a lady’s sleeves, pale grey and white and silver silk that looked like mist on the floor. Even in the darkness, he thought that the shadow lying across the cloth must be a lock of her long, black hair.

He bowed from his cross-legged position. “Thank you, my lady, for your hospitality.”

“You are very welcome,” a voice came from behind the screen. “My maid said that you were set upon by bandits. I trust you were not injured.”

“Only bruised and cut a little. Your spring has helped that.” Intrigued by her voice, the young man crept a little closer. He told her his name and, knowing that it would hardly be polite for a well-bred woman to tell him hers, decided to call her, in his mind, the Lady of the Autumn Moon. Sipping the wine, he told her how his party had left the capital and been attacked by the bandits. “Your house was a most welcome sight, my lady. How did you come to live so far from the world, in such a remote spot?”

“My father brought me here, many years ago,” she answered, though her voice sounded so young that he decided she must have been a mere babe at the time. “When he died, I remained.”

“Are you alone here?”

“Only I and my maid remain. The other servants all left with my father’s death.”

“What a terrible life for a young woman,” the young man observed, “Have you no family? No one to take you back to the capital and see to your future?”

“I have only myself.”

“Believe that your kindness to me will not go unrewarded,” he assured her, resolving to help but privately uncertain what resources he might still have. Would it be possible to take her to his new home? If she were as beautiful as her voice suggested, he might be able to set her up as his concubine.

“Your kind thoughts are thanks enough, my lord.”

“Nonsense,” he answered, then decided to try to persuade her with poetry.

“Lovely in a lonely garden—but how much more

precious is the plum-flower when it is seen.”

He heard the rustle of her silks and the sleeves of her gown moved beneath the screen like a pale hand.

“The moonflower scents the night

But in the day you would pass it by,”

she replied and he was moved by her wit even as he was intrigued by her resistance.

“I would wait all night for the moon

and let the morning dew wet my sleeves

if she did not come.”

He was waiting for her reply when the old maid reappeared and crouched into the room.

“I have prepared a chamber for you, my lord. Surely you are tired and wish to rest.” The young man was annoyed to be interrupted in his flirtation with the Lady of the Autumn Moon, but, when he looked towards the place where she sat, she said nothing and so he was compelled to follow the maid down the veranda to his chamber. And, in truth, he was so wearied by the events of the night that he was asleep as soon as he lay down.

In his sleep, strange dreams came. He dreamt that he was wrapped in a silken web, like that of a spider, while something probed and lapped at the cut that the bandit had made on his shoulder. The dream so disturbed him that he awoke in the middle of it and, without thinking, struck out at the heavy darkness with the first thing that came into his hand, the comb which the old woman had given him to arrange his hair.

There was a cry of pain and he came fully awake. In the moonlight, he could see a young woman crouched on the floor, holding on to her hand. She was more beautiful than he had imagined, her face as pearly as the moon, with fine arched brows and a mouth red as a cherry. Hair the hue of midnight fell over her shoulders and pooled on the mats around her knees. Gossamer robes drifted about her, baring her shoulders. “My lady . . . please forgive me. I dreamed. . . .”

“I came to see if you were well,” she said softly.

“Did I hurt you?”

“My hand bleeds. It is nothing.” Despite her protests, he took her hand in his and kissed the bloody streak his comb had left across her soft, cool skin. Her blood tasted like a strange, exotic spice. When he looked into her eyes, they were very dark. Then she drew her hand away and rose to her feet. The moonlight seemed to shine through her robes, outlining her slender body.

“I must go.”

“No.” He was half on his feet before he thought, hand out to reach for her.

“You would have me stay?”

“Yes.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes,” he answered and caught her sleeve in one hand. She opened her arms and the robes fell away, leaving her naked body gleaming whiter than the silk of the moonlight. Then he pulled her down onto the mats and drowned in the nets of her hair and cool depths of her flesh.

When he woke, the room was in darkness and he was alone. The scent of her hair clung to him, the taste of her blood was in his mouth. A great weariness hung on him like a burden and it took many moments before he could rise from his blankets and stumble to the doorway. For a moment, he stared unbelieving at the sky and the moon that rode high over his head. It had been that way when the Lady of the Autumn Moon had come to him and surely it must have sunk away during the long hours he had spent in her arms. If the sky were true, he had slept the whole of one day and part of the night.

Then he looked about him and his disbelief deepened. The garden that the previous night had been merely overgrown was now choked in weed and vines. A tree bent over the pool in which he had bathed, dropping its leaves to lie on the clouded water. The house around him was equally changed. The heavy eaves had collapsed in places and the wooden veranda beneath his feet was crumbling with rot.

He rushed from room to room, calling for the lady or her maid, but there was no answer save for an owl’s mournful cry somewhere in the forest.

As he searched, there came the dreadful realization that the lady with whom he had spent the night was no mortal creature, but some ghost or demon into whose lair he had wandered. Her evil accomplished, she had returned to whatever strange realm might claim her.

For the second time, the young man fled through the woods, leaving behind the ancient, decaying house and the haunting cries of the owls. But he could not flee from the strange and terrifying hunger the lady had left in him and he knew, now that it was too late, that the omens had been true and his journey cursed from the very first step.

October, 1902

It did not happen exactly like that of course.

The lady was less supernatural than the story would suggest. The young man was certainly more arrogant.

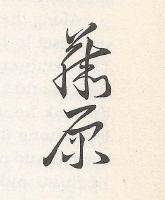

But we of the Fujiwara family love words almost as much as we love power and we have given this country great poets as well as manipulative regents.

When I wrote this journal in my own language, it seemed that I could not help but turn the events into art, the reality into fiction. Fiction was safer for me.

Now that I have resolved to translate it, as practice in the English which I have struggled to learn, I have also resolved to try to keep the poetry but to add some truths to it as well.

The diary was dangerous when I began it and is more dangerous now. Yet it is important to me to continue it, to translate it. Perhaps it is only vanity, though I prefer not to believe that. Over the centuries, I have written it for many reasons. It records a past I have feared I might forget. It has allowed me to gain whatever understanding of my state that I have achieved. So I shall continue, despite the new risks that have arisen.

I have read Mr. Stoker’s book. Though I puzzled through it in his native tongue and not mine, one thing is clear.

The West has words for what I am, even if the East does not.

I am, of course, the young man whose unfortunate journey is chronicled in the first tale of this diary. My name is Fujiwara no Sadamori (I cannot yet think of it backwards, as the West demands). I was born in AD 1015, as the West counts years. In thirteen years, I will be nine hundred years old.

It took me some time to determine the nature of my curse, as I had no convenient mythology to guide me. I searched all the tales of ghosts, demons, and shape-changing creatures that I could remember, but I could find nothing that described my state. During this first time of despair, I wandered in the woods. I almost perished when I fell asleep in a meadow and woke to find the sun burning my flesh, as if it meant to sear it from my bones. I was racked with hunger and thirst, unable to stomach either water or such food as I could find. It was not until I managed to kill a rabbit and bit its throat to drain its blood that I discovered what I now needed to survive.

On the fourth night after my encounter with the Lady of the Autumn Moon, I came upon a peasant in the woods. I thought that I meant only to hail him, to seek his help, but when he saw me he was frightened. The chase was brief, for I found that I had new strength and speed, despite my hunger. When I caught him, it seemed that a kind of madness came upon me. When it faded, the hunter was dead and my throat was burning with his blood.

I stayed three more nights in the forest, torn between terror and fascination at what I had become. And last, it became clear to me that the curse, the dark change the lady had wrought in me, had not turned me into a mindless monster. I could not creep about the woods and hills and be content.

At last, after a long debate with myself about my course, I went to my new posting and said only that I had been attacked by bandits, barely escaping with my life, and, lost and ill, had wandered in the woods for several days.

I had odd habits, but no one in the province knew me and the locals were willing to believe any eccentricity of a court aristocrat. The barons and their warriors thought me effete for my careful avoidance of the sun. The concubines offered to me thought I was some strange sort of monk, saving my seed to gain greater enlightenment. I do not know what the peasants upon whose blood I fed thought of me, if they had time to think in the moments before they died.

Gradually, I began to realize that while I was more than mortal, I was less than an all-powerful demon. I had no magical powers beyond my new strength and a will that, with practice, I could briefly impose on others. As the years passed and, behind the powder that whitened it, my face stayed the same, I began to think that I might not die.

The time went by with surprising speed. Once I passed beyond the stage of blind obsession with my new existence, I found that my life was not all that different than the one I had expected. I did what governing was required of me and watched the nobles around me ape the court of Heian-kyo, hoping through poetry and moon-viewing and the careful cultivation of a fine hand that they could join the “dwellers among the clouds” and knowing all the while that the rank they coveted could be granted only by blood, not by achievement. They thrust their daughters at me and some I took, after my fashion, though of course none of them ever produced the heirs upon which their families had counted.

Twice I went into the forest to search for the Lady of the Autumn Moon but there was no trace of her. I was never to see her again.

After forty years, I announced that I was retiring and, after a pilgrimage to Ise, would become a monk. After nights of feasting and gifts, I started back towards Heian-kyo. As before, I was not allowed to travel unescorted and so rode with a company of ten. Four bore my palanquin, two were servants, two, soldiers from the local garrison. The last were sons of a local family, who hoped to find their future in the capital or the monastery.

We were one day into the mountains when the bandits attacked. As I waited in my palanquin, they killed all my escort save one; one son was allowed to escape back down the trail. As the sun sank, I stepped from the concealing curtains and onto the darkening path. Five bandits were there, three stripping the bodies of wealth, one digging through packs searching for wine, the last watching me with a faint smile. When he held out his hand for the promised payment, I killed him and then his fellows. I left one of my bloody robes on the pathway. When the authorities came upon the bodies they would assume that my escort and the bandits had perished battling each other and that I surely must have crawled into the woods to die.

Alone, I set out for the home of my childhood.