Blood and Chrysanthemums (18 page)

The singer was very bad. Takashi Yamagata listened to his off-key rendition of “Long and Winding Road” and wished suddenly for a gun.

He had one, of course. It was concealed beneath the seat of the rented limousine. It would hardly have been polite to bring it into the karaoke bar. He had left that to Jiro and his other men.

Yamagata spared a glance at the table across the room, where his men sat. They were trapped between their urge to have fun, to join in the drinking and singing, and their profound uneasiness that he was an entire room-length away from them.

He wasn’t supposed to sit alone. He wasn’t supposed to even wish to. That he did made him an oddity, the same way his Harvard education did. It was a fact he used to his advantage; After all, the

oyabun

was odder still. This similarity between them strengthened his position.

Right now, he couldn’t think with his men crowded around him. He needed emptiness around his body and the anonymous wail of the karaoke in his ears.

He lifted the glass of Scotch to his lips and took a sip, savouring the heat in his throat. Is this what it is like? he wondered. Does it burn going down the way liquor does?

The warmth spread but could not ease the tightness that seemed to encircle his chest. As long as the question remained, so would the tension. What did Fujiwara know? What was he doing here in Canada? If he knew everything, what would he do about it?

The message waiting at his hotel room had been terse and unrevealing. “Stay away from Dr. Takara. The matter is being dealt with.” There was no name on it, only Fujiwara’s seal.

How had he known?

Yamagata looked at the

yakuza

clustered at the far table. There was a spy there, of course. He had suspected it for a long time. Most of the men believed they had been following the

oyabun

’s orders all along. There was little risk of them discovering otherwise, for they hardly knew Fujiwara well enough to have a personal conversation with him.

How long had Fujiwara known? Was it possible he had only discovered recently? Not likely, Yamagata acknowledged with a rueful grunt. Fujiwara had known all along and let him proceed for reasons of his own.

He took another drink, a gulp this time.

He had been over this a thousand times in his mind already. Dr. Takara was off-limits, which meant she had told Fujiwara things she had not told him. Fujiwara had not ordered him to return to Japan, which meant he either wanted Yamagata here or did not care.

The safest thing to do would be to simply wait here in Vancouver until he received more orders.

But if he did the safe thing, then everything he had worked for over the last ten months would slip away. All the plotting, the expensive acquisition of the snuff films, the manipulation of Dr. Takara . . . all of it would be wasted. He would have walked the knife edge of betrayal for nothing.

Someone else was singing now, a passable bass rendition of another Beatles song. It made him think of the summer he had turned fourteen, working in his father’s noodle shop when he wasn’t studying.

That’s where I saw him for the first time, he thought, eyes gazing unseeing into his drink. Fujiwara walked into the shop and my father bowed to him and gave him the best table we had. He and his men paid for nothing, at my father’s insistence. His men were flashy; black suits, white ties. Some of them were missing fingers. He was quiet, though, in his expensive, handmade suit and white shirt. Father let me help serve them and I saw Fujiwara watching me as I worked. I remember my face burning as my father bragged about me. “My son works very hard, studies very hard. He will go to university.” I supposed I would. My mother and father were counting on it. But I could not help but wonder if these gangsters who seemed so confident and wealthy had gone to university. I wondered if

he

had.

When they left, I asked my father who they were. Fujiwara-san, my father told me.

Oyabun

of the Makato-gumi

yakuza

. We were honoured by his presence, he assured me, even while I remembered him cursing the protection taxes he paid to the same organization.

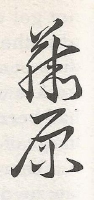

A year later, his father and mother were dead, killed in the fire that destroyed the noodle shop. All of the protection money in the world could not prevent a spark from igniting or wood from burning. As he stood in the smoking ruins, trying hard not to weep, someone put a card into his limp hand. When his mind cleared enough to look at it, he saw the crest and the name,

From that moment, Fujiwara Sadamori and the Makato-gumi were his family. He had gone to university on money he earned through his part in their protection, gambling, and prostitution enterprises. The Makato-gumi had sent him to Harvard to obtain an MBA, to help them launder their dirty money through clean businesses and expand their reach beyond Japan and the East. He was not trained to be a thug, though he was taught to kill in a dozen ways. He was trained to be a ruthless, clever businessman. The older

kobun

might have disapproved of it, hating to have a young man rise so quickly, but they bowed to the

oyabun

’s orders and pocketed their portion of the organization’s growing profits without complaint. By the time he was thirty, he was Fujiwara’s most trusted lieutenant.

Trusted enough to be permitted to know his

oyabun

the way the other

yakuza

did not, to be told why instead of simply given orders. To be given more and more responsibility as Fujiwara began to withdraw from the everyday operation of the organization. To spend time with Fujiwara in order to learn from him and sometimes for no reason beyond the pleasure they found in each other’s company.

Trusted enough to go to his estate in the mountains, Yamagata thought with a bitter edge. Trusted enough to be allowed to discover, subtly, delicately, what he really was. There were never any words between them about it. Fujiwara let him see the old portraits on ancient scrolls. He let him see poems written in a shockingly familiar hand, six hundred years ago. And the one night, he had allowed him to see, from the shadows, the moment when Akiko lifted her wrist and Fujiwara drank her blood.

With a shudder, he dragged himself back to the present, to the noisy bar and his unsolved dilemma.

The safest thing to do would be to wait . . . but he had not got where he was by doing the safe thing. That was what the

oyabun

valued about him, he was sure. That he did not always do what was expected. If that made him a freak, a traitor, so be it. He was committed to his path and had been since the moment he had seen the videotaped image of a girl’s torn throat and a man’s bloody mouth.

There was an obscure comfort in the thought, as if a fate he did not believe in had decreed his actions and he had only to carry them out.

He pulled the cellular phone from his pocket and dialled the series of numbers that would connect him to the Makato offices a world away. Someone there would know where Fujiwara was. Kojima or one of the others would surely tell him.

After all, he was Fujiwara’s most trusted lieutenant. He was Fujiwara’s heir.

The world has ended.

Once, I had a dream of dying by fire. I thought its prophecy was meant for Tomoe but I was wrong. It was meant for me. It was meant for everyone.

I sit here in the darkness, in the shelter of this ruined house. I know that it is night now though the sky, visible through the tumbled boards above me, seems no different, no darker than it has all day.

It has been many years since I walked uncloaked and unprotected in the daylight.

I have vomited blood again. Its black splatters make cryptic patterns on the grey ash that covers the ground. I hope that my illness is only due to shock.

I came here to escape. The thought of it amuses me now. I fled Tokyo’s fires and bombings and the ruins of my empire, however small it had been. The war had stripped me of almost everything. It had taken Toru, my trusted mortal assistant. It had taken even my estates. Only here, in this one place, I still had interests that were untouched. So I made my careful way across the country.

The city had been damaged enough that I had no trouble finding a place to shelter in the rubble of a ruined building. Beneath the tumbled mass of stone and wood, I found a haven where I could sleep away the day. I supposed that it was possible I might be discovered, but I preferred the risk to the trouble of finding an inn where I might rest undisturbed. My mind full of my plans for the next day, I fell asleep.

It was the great shudder of the ground that woke me.

Earthquake. That was my first confused thought. I lifted my head, still stuporous with the weight of sleep, and then something struck my shoulder. The pile of rubble above me groaned once then seemed to shift and waver. Dust brushed my eyelids and I had barely enough time to curl up, arms over my head, before the whole of my hiding place collapsed on top of me.

Strangely enough, I slept again. My weariness, heightened by the fact that I had not fed in several days, was so great that even the strange destruction did not alarm me. The fall of the debris stunned me but did no serious damage, and in an odd way I felt protected by it.

I do not know what woke me the next time but I knew instinctively that only a few hours had passed. For the first time, panic stirred inside me. Fires often followed earthquakes, as I had painful reason to know. If one had started, there was no telling how close it might be to me. I sniffed, certain I could smell smoke even in the stale air of my refuge.

It took a longer time than I expected but at last I worked my way through the worst of the rubble and squinted through a broken board at the world outside.

It was dark. For a moment, this confusing fact occupied my mind. I blinked but painful sunlight did not replace the soothing darkness. Could my time sense have been so altered?

Then I heard the wailing. Voices cried out in pain, called out for mothers and fathers, wept for sons and daughters. Not an earthquake, I thought then. An enemy attack.

I pushed the final boards away and dared a look outside.

I said long ago that we Fujiwaras are poets, that we love words. But whatever words I write here can never be anything but pale ghosts of the terrible reality I saw. The sky was black with smoke and dust, the sun burning through only as a faint sickly orange glow. The houses around my ruined shelter were ruined now as well, flattened as if some great wind had passed and blown them down. Boards and pots and burned clothing and personal possessions littered the streets.

Figures were passing by and for one mad moment I thought that it was the Night Parade of the One Hundred Demons, that a superstition of centuries ago had come to life before me. Then I realized that they were not demons passing me but people.

People burned black and rust-red, their hair scorched and white with ash. People with skin that hung like rags from their arms, revealing the crimson flesh and white bone beneath. Women carrying children with lolling heads and blank eyes, gone far away from the comfort their mothers crooned through lips broken and bleeding from thirst. A group of school girls limped past, weeping in pain from the shards of glass embedded in their naked backs.

On the ground sprawled bodies so black and twisted I could not tell whether they lay on their backs or fronts. From the wreckage of the houses around me came faint cries for help, pleas that barely touched the empty-eyed survivors shuffling past. A weeping man dug at the shattered remains of his home, his hands bleeding.

I struggled from the embrace of the rubble and emerged into the nightmare. There was nothing but destruction as far as I could see; devastation and fires and bodes. The smell of burning flesh drifted on the faint breeze. When I clambered on top of the remains of my shelter, I could see the river several blocks away, bloated with the drowned who had thrown themselves into it seeking relief as their bodies flamed.

Whatever had done this was not an incendiary bomb or the concentrated bombing that had turned Tokyo into a firestorm.

It seemed a long time that I sat on the rubble and watched the walking corpses pass. For so they seemed to me, even the ones who looked undamaged. I could smell the death on them.

At last I looked to my left and saw that the line of fires had reached the base of what had been this street. With numb practicality, I crawled back into my refuge and retrieved my case of clothes and belongings. There was nothing to do but join the stream of refugees leaving the city.

I walked for a long time, passing the slow-moving procession until it seemed I left it along the dusty road.

The sky had gradually begun to lighten and I realized that I would soon have to seek shelter again.

But first I would have to feed.

My mind shied from it, from the thought of my mouth against blackened skin, but the old instinct to survive was stronger than any scruple or revulsion. Surely these people must understand that, I thought as I paused again at the side of the road and watched the hollow-eyed multitude stumble on. What else keeps them walking on their burned feet, their skin falling from their fingertips? What else wraps their mind in such shock they do not even really know what has happened to them?

We are all walking corpses on this road, I thought again. I am only the most accustomed to it.

Several miles down the road, I spotted the ruins I now sit among. A heap of tumbled rock and wood, they were an echo of what we had left behind. I do not suppose anyone else in the sad parade even noticed them. I had stepped off the road, preparing to cross the field, when I noticed the crumpled figure in the ditch.

It was a young boy, no more than ten years old. The charred remnants of his school uniform clung to his thin body.

The terrible burns covered his right shoulder, arm and the side of the face but the rest of his body appeared untouched. Still, when I put my hand on his cheek I could feel the death in him.

He opened his eyes and looked at me blankly. “Mother?”

“Hush, child,” I said, because it seemed I must say something to answer that plaintive question. If I left him in the ditch, would his mother come trudging past and claim him with glad cries?

“She was bleeding,” he muttered. “Blood all over, all over . . .”

His mother must have perished in the original devastation, I decided. How easy it was to decide that, to presume what would leave me with the least regret. But I decided it nonetheless, just as I decided that the boy was dying.

No one said anything as I bent to lift him from the dirt. No one protested as I set off across the field with his limp body in my arms. In my bleaker moments, I believe I could have drunk from him, there in the ditch, and no one would have stopped me. What was one more horror after so many? What was one more death?

The boy was crying softly, weeping with pain from his injuries, when I set him down in the shadow of the ruins. “Did you see what happened?” I asked him curiously.

“There was a B-29. I saw it up in the sky. We all pointed at it. Then there was a big flash of light and I fell down.”

The boy coughed and blood trickled from his mouth. “I fell down.” He lay still for a moment, looking at me. “Am I going to die?”

“Yes. I think so.”

“I don’t care.” For a moment, there was a trace of the stubborn defiance so typical of little boys in his voice. “My mother’s dead, everybody’s dead. I don’t care.”

But he did and it tore at my heart. I could take him back to the road. I could choose another to be my survival. “Do you want me to take you back?” I asked and he shook his head.

Another coughing spasm racked him and his body shuddered in pain. I knew I would not take him back. What other could I choose that would not be like him, torn between living and dying? The dead would do me no good, despite their numbers.

But though I would do what I must, I would do it with kindness, I resolved. I would not frighten him, for surely he had endured enough on his terrible day. I would wait until he slept.

I took off my shirt and put it under my head, then sat beside him. When he whimpered for his mother, I took his unburned hand in mine, surprised at the strength that lingered in the thin fingers. There was a strange fever in him and he tossed and wept and whispered and could not sleep.

I could feel death waiting in the gathering darkness and knew that it might take him before unconsciousness did. At last, I could wait no longer. I crouched over his prone body and tilted his head to reveal the unburned side of his throat.

As I bent my head, he opened his eyes and looked at me. I do not know what he saw, for I do not think that it was me, but he smiled. I put my mouth against his vein and drank.

If it is safe tomorrow night, I will put his body back by the road, so that it can be found and properly cremated. I do not think anyone will question the two tiny marks on his throat.

His blood did not stay in me for very long, but I hope that it has been enough to sustain me over the next nights. I have to leave this place before the bureaucracy of emergencies begins to take over. It will not be enough, of course. There is probably not enough medicine in all the world to heal the wounds I have seen. There is certainly not enough medicine left in Japan. I am grateful that I will be spared that, at least, spared the long nightmare of painful dying.

I do not want to think about moving on now. My throat hurts. I feel disoriented, strangely delirious. I think perhaps it is because I have been awake all day for the first time in centuries. Even my fingers feel numb and it is growing hard to write.

I think that it is over. The war, the government’s dreams of empire and expansion, the nation’s old terrible belief in its own inevitable greatness.

It is over for me, as well. I have had a hundred years of peace and prosperity, even ease. I do not think it will ever be so easy for me again. Whenever it is, whenever I think that I have risen above and beyond the thing that I am, I will only have to remember the blood of a burned and dying boy.

I have kept this diary for more than nine hundred years. I have believed it was important to keep a record of my life. I have believed in the power of words to transcend time, to live longer than even I can hope to exist.

But there are no words for this day, no words that can matter. I will write one more line and then put this diary away, perhaps forever.

The world has ended and even I, well used to endings and death, cannot help but grieve.

August 6, 1945