Blood and Chrysanthemums (15 page)

Like long-time conspirators, it seemed they needed few words. Hidekane left the room. A suitable time later, the lord too retired. At the appointed time, they met in the garden. The chilly air turned the poet’s breath to icy mist but the lord wore only his silk kimono and did not shiver. “Who are you?” he asked, his voice quiet and calm, but cold as the moon above them.

“Ito no Hidekane. Who would have been Fujiwara no Hidekane, had you not slain my father.”

“Your father, if you claim to be the child of Kozun, betrayed me.”

“My mother told me the true tale. How you came to my father fifty years ago and offered to adopt him into your family, to give him your estates upon your death, because you had no children of your own. But you did not die, for you are an unnatural demon. You merely went away and, when you returned, killed my father and my brothers to take back the honours you had given him. She was fortunate to have escaped your murderous treachery.”

“Your father’s wife was two years dead when I returned.”

“My father’s maid was not. You did not know that, did you? That she was his mistress and carried his child. You did not believe that she would remember the foul things you did to her, that she would see through the dreams to the demon that you are.”

“I remember her now. Though,” his voice turned languid, “I do not recall her fear of foul dreams. Indeed, it seemed to me she went eagerly to sleep each night, perfumed and willing.”

For a moment, fury painted its mask on the actor’s face. But then he mastered it and continued, as if this were but another play and he had lines yet to say.

“As I grew older, she could no longer afford to keep me and so she gave me up to a passing troupe. But she had told me the story every night and made me swear to remember it.”

“And so here you are, a master of your own company. A playwright of some talent, I admit. Though your mother’s story had more fiction in it than your play. No, do not interrupt me. I endured your tale this night, now you must hear mine. I did indeed adopt your father and allow him to inherit this land. But there were conditions. He was not to impoverish it. He was not to disgrace the Fujiwara name. And when a young man bearing the family crest on his sword came to him, he was to adopt him in his turn and leave him the estate. This was all I asked of him. Fifty years of wealth, and even a portion of the rice crop to any sons of his own I might displace, and all he was required to do was adopt me and give me my ‘ancestor’s’ name.

“But he grew greedy. He misused the wealth of this estate. He antagonized my neighbours. And when I returned, he denied his sworn oath and his duty. He refused to set his own sons aside. Eventually, he agreed, when I held their lives as hostage to his bond. But still he plotted against me or, more truthfully, against the young man he believed I was. Eventually, he began to suspect the truth. Perhaps your mother aided him in that, believing she would one day be lady of the house.

“I gave him every chance to live out the rest of his life in honour and comfort. I gave to him the same chance I gave others over the years. They made the honourable decision and did as they had promised. But your father gave me no other choice. He had even involved your older brothers in his plots.”

“And so you killed them all.”

“Yes. That has always been the price of treachery.” The words had the coldness of harsh truth. “Why did you come here? To slay the demon and take back your false inheritance?”

“No,” Hidekane said, after a moment. “I thought of that for many years. But I am not a swordsman. My only weapons are words. My play, the truth of your evil, is my revenge. It will live longer than either of us, as my curse upon you.”

“Your play held a core of truth,” the demon-lord admitted after a moment. “Your heart knew it all along. For whose soul did you embody on that stage? Your father’s . . . or mine?”

For a moment, the poet would not look at him but instead stared at the dark, dead trees that surrounded them. “You curse is to be what you are. My curse is to imagine it too well,” he said bleakly at last.

“I am not cursed. I am only what I am. I have no wish to change . . . or to die.”

“Now. But someday . . .” There was a strange distraction in his voice, as if he had left the careful rhythms of his script and grasped now for some truth he had never articulated. “Someday my words may be yours.”

“Or perhaps, Master Hidekane, it is your own epitaph you have written.”

“Do that, if you wish, Lord Demon. Kill me. But if you do, it will only make my words stronger.”

“You cannot perform that play for Lord Konishi,” Lord Sadamori said and the playwright knew that he would not die that night.

“No, nor for any other audience. Not the way it is. But I have already written another version that will suit. I am certain it will be very popular.”

“A hundred years from now, no one will know your name,” Lord Sadamori pointed out. To his surprise, Hidekane’s mouth twisted into a thin smile and he bowed with graceful, mocking respect.

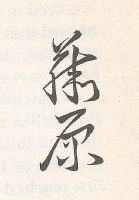

“

You

will, Fujiwara no Sadamori.

You

will.”

October, 1902

And I did remember him, more than once in the years since that frosty night in the fifteenth century. There was some truth to the divided demon he embodied on stage . . . but I was never only that. As the years went on, I both hated my state and revelled in it. I longed for death and clung to life. I lived on, because I could not do otherwise, and yet much of the process of that living was no different from that of any other man in my land. I had my joys and griefs, my dangers and my delights.

There were narrow escapes, especially during the long wars that racked the land throughout the sixteenth century. I tried the adoption ploy once or twice more but when both times ended in bloodshed, I was forced to abandon it. I developed new stratagems for survival, new lies to protect myself. It helped that my ancestral lands were neither too rich nor too near the centre of power. It helped that my soldiers were always well trained and well led, the beneficiaries of whatever wisdom and cunning I had acquired in six hundred years. And, perhaps most of all, it helped that I always chose the winning side. If I had not, especially during the last, terrible battles, I would surely have lost everything.

I watched Oda Nobunaga become shogun and defeat the warlike monks of Mount Hiei, breaking the power of the Buddhist priests. I was on the field when he used the firearms he had bought from the foreign Portuguese who first reached our shores in 1542. They had tried to give us their god; we took their guns instead. Many of the southern barons converted to Christianity. No doubt, some of them did it in true faith. The rest did it for the control of the cargoes of silk and riches that the barbarian traders brought. The foreigners intrigued among themselves, Portuguese against Dutch, Jesuit against Franciscan, for the right to save our souls and take our wealth.

When Nobunaga was assassinated, one of his generals, Hideyoshi, came to power. Tokugawa Ieyasu, secure in his eastern provinces, helped his rival consolidate power over the rebellious

daimyo

, then took it for himself upon Hideyoshi’s death.

After Ieyasu’s victory, there came peace of a kind. It was the peace of denial and repression, of secret police and hierarchy. The foreigners were sent away. The followers of their alien god were persecuted or killed. No Japanese could leave on pain of death. No Japanese who had left could return on pain of death. No commoner could leave his land. No commoner could carry weapons.

Things were easier among the aristocracy. The two swords in my sash entitled me to many things, including the unquestioned right to cut down any commoner who did not show me sufficient respect. If we were required to spend half a year at the court in Edo and leave our families there as hostages for the other half, it was surely a small price to pay to the shoguns whose policies preserved our privileges and wealth.

The Tokugawa shoguns believed that they could freeze Japan in a shape that they could forever dominate. They believed that they could stop time.

For a time, I believed it as well.

Dimitri Rozokov set down the leather-bound book. How long had he been reading, he wondered. How long had more than five hundred years taken to pass through the words into his mind?

The tiny apartment suddenly seemed smaller, more stifling, than ever before. He needed the cold kiss of the autumn air to break the spell the words seemed to have cast upon him and help him think clearly. The diary still in his hand, he rose and went to the door, then stepped out onto the landing.

In the clear night sky, he saw the passage of time. More than three hours had vanished since he had retrieved the wrapped book from the stoop and begun to read it. He pulled his coat tighter and took a deep breath of the cool air.

Almost a thousand years. If the book was true, if he still lived, Sadamori Fujiwara was almost a thousand years old.

Rozokov pushed the thought away and let himself contemplate all the questions his absorption in the diary had blotted out for those long hours.

Who had left the book for him? Whoever had done it, they must know his true nature. He did not believe anyone in Banff had that knowledge. Leigh had made it abundantly clear, if only unconsciously, that she did not remember him.

Had Ardeth somehow betrayed her true need to Mark Frye? His attitude the other night did not suggest that. If he had suspected Rozokov, he would hardly have come to his rival’s door alone and at night. The young man did not seem to be the sort who would have possession of such a book—or could concoct it.

Could someone have emerged victorious from the power struggle in the crumbling Dale empire and discovered the truth behind Althea’s final madness? If that were so, the diary seemed an unnecessarily subtle and dangerous ploy. Surely it would make more sense to take him by surprise than to warn him of possible danger.

Was the diary true or false? If it were a forgery, it was an impressive one. But if someone were to falsify the diary of the vampire in order to signal him that his nature was known, why would it be a vampire from a culture so distant from his own? Because he would be less likely to spot any historical inconsistencies in such a tale than in a story set in Europe? He had to admit he knew no more about the history of Japan than had been publicized in the newspapers of this century and the last.

If it made no sense for the diary to be false, then it would follow that it was true. The vampire had taken a great risk, one Rozokov himself had never dared. To commit to paper the darkest secret of one’s existence . . .

Whoever wrote it

knew

, he thought with a shiver that had nothing to do with the cold. Whoever wrote it understood the terrible beauty and monstrous evil, the contradictory urges for life and death, as well as the playwright Hidekane had.

Rozokov looked up at the moon. The words came back to him, whispered in his mind in a strange combination of English, his old half-forgotten native tongue and an unknown Oriental language.

The moon must rise again

as I must rise

There is no rest.

He dragged his gaze from the sky and forced himself to scan the quiet alley, the shadowy yards around him. If he accepted that Sadamori Fujiwara was a vampire, what did that mean? To automatically assume that he meant no harm would be foolish. Rozokov remembered the first night he had met Jean-Pierre and the testing that had gone on between them, the struggle for dominance that had finally been resolved in their friendship. It was possible that he and Ardeth had wandered unknowingly into this vampire’s territory and the diary was his way of warning them away.

But would any enemy care to have his life, his secrets, so revealed to a foe? If Fujiwara did indeed want this town for himself, there were certainly less personal ways in which to send that message. If the diary was an accurate portrait, Fujiwara did not seem to be the sort of vampire who would fear others of his kind. Though there was an undercurrent of ruthless pragmatism in his stories, they did not suggest that he would act violently without reason. Rozokov could find nothing in the words he had read to suggest that Fujiwara would wish him harm. Perhaps the diary had been sent not to warn off an interloper, but to introduce a friend.

Rozokov frowned unconsciously. He had to admit that he liked the man revealed in the diary’s pages. Sadamori Fujiwara had an intriguing wit and clear-eyed, even cynical, honesty, wrapped though it was in artifice. Each story, each comment that Rozokov read strengthened his desire to meet the writer.

There was another reason beyond the promise of wit and intelligence, he acknowledged. If Fujiwara had survived nearly a thousand years, then surely the old vampire had found the answers to some of the dilemmas that had so recently torn Ardeth and him apart, that had kept him entangled in doubt and depression.

I would be like a child to him, Rozokov realized suddenly. As much as Ardeth is to me. A great wave of longing swept him suddenly. To the vampire who had made him, he had been victim, lover and then betraying angel of death. To Jean-Pierre, he had not been able to help being an elder brother—even when the two of them were taking mad risks in the salons of Paris. To Ardeth, he was failed father, failed lover. To Fujiwara, so much older, surely so much wiser than he, he could be something else. He could surrender responsibility for once. He could learn instead of teach.

He could be son instead of father.

Shaking, he leaned on the landing railing and stared down at the book in his hands. Throw it away, part of his mind urged. Throw it away before you want everything it promises too badly. Throw it away before it destroys you.

Or you destroy it, the way you have destroyed every other vampire you have ever met.

The leather was warm and soft under his fingers. He opened the book slowly. Just a little more, he told himself. There must be a reason for this to exist. I will never find it if I do not read just a little more. The spidery, beautiful writing caught him in its spell again.

Oblivious to the chill, he sat down on the top step and began to read by the light of the bright moon over his head.