Bette and Joan The Divine Feud (8 page)

In July of 1932, when

Rain

was finished, Joan and Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., went to Europe. "It was a last fling—an attempt to revive the thing they saw going—their happiness," said

Modern Screen

writer Katharine Albert. In London, Joan was mobbed at the theater by fans who tore the clothes off her back. "I was thrilled," she said, claiming

that

was the highlight of the trip. Neither England nor France lived up to the movies she had seen. "She absolutely hated every minute of it," said Fairbanks. "She couldn't wait to get back to Culver City. It was like going back to the womb, the only place she felt secure and confident in herself."

Back home, at M-G-M, Joan threw herself into work. While practicing her dance routines for the forthcoming

Dancing Lady

musical with Fred Astaire, she was spotted by Ethel Barrymore, on her way to an adjoining soundstage to work in

Rasputin.

Pausing to watch Joan tap dancing at top speed, grande dame Ethel patted her brow and commented aloud, "My dear, it's wearing me out just looking at you."

"Work was the only opiate she had," said Katharine Albert, who visited the star that spring to talk about her next picture. Joan, pale and thin, having lost fifteen pounds in her anguish, said to Albert, "Forget my next picture, I've got an exclusive for you. I'm dumping Doug." The news of the divorce was to be kept a secret by Albert and

Modern Screen.

No one, including Doug, was to know of the divorce until two months hence, when the magazine hit the newsstands.

"This was a big scoop for

Modern Screen

(and its 3 million readers)," said Ezra Goodman. "Joan was being loyal to a dear friend." Katharine Albert wrote up the story and sent it in to the magazine. It was already set in type, ready to go to press, when Doug made the tabloids on his own. He was being sued for sixty thousand dollars by one Jorgen Dietz, said to be a Danish baron. Dietz contended Fairbanks, Jr., stole the "love and affection, comfort and assistance" of his wife, Mrs. Solveig Dietz. He also claimed that Fairbanks, Jr., and his manager, in an effort to silence him, "imprisoned him for four hours in a hotel room without his authority."

Naturally, this upset Joan greatly. "It is an outrage," she told reporters. "There is no truth whatever in the charges." It also put her on the spot with the imminent news of her plans to divorce Doug, coming up in

Modern Screen.

"This was her dear husband," said Ezra Goodman. "Should she be a bitch and leave him after this? It would put Joan in lousy with her fans, as a lousy, stinking wife with no understanding. A woman does not do this. A woman stands by her man." Joan called

Modern Screen

and said she was not leaving Doug. The magazine screamed that she couldn't do that to them. It would cost them a fortune. "She wanted to play the role of the forgiving wife," said Goodman. "Was she to let down her husband or her friend or the fan book? She finally decided to let down her husband."

Joan told Katharine Albert and the editors to let the story stand. She would divorce Doug, and stall the press until their exclusive broke in the magazine. But, two days before the issue went on sale, Joan received a call from Louella Parsons. The columnist was preparing a positive story on Joan and Doug. "It was a whale of a story," said Louella. "I had Joan standing shoulder to shoulder with Doug, staunchly defending their happiness and their marriage." She called Joan, for quotes to give the column "punch." Joan asked for time, begging Louella to hold off, promising that she would have another story for her in a few days. Minutes later, smelling the scent of her own scoop, Louella was on her horse, galloping to Joan's Brentwood house. She barged in, held Joan's hand, and pulled the news out of her. "Right under my surprised hostess' eyes," said Lolly, "I grabbed her portable typewriter and started banging away on my own yarn, before the competition could arrive."

The next day the tragic news of the official split between Crawford and Fairbanks, Jr., was on the front pages of the entire Hearst newspaper syndicate. The timing and enormous coverage were beneficial to Joan but not to Doug—or to Bette Davis, whose first starring picture was released on the same day. "Everyone wanted to know about Poor Joan," said Adela Rogers St. Johns, "how she was holding up. I remember one of her friends, Ruth Chatterton, had plans to leave for Europe with her husband, George Brent. She told Joan she would cancel her trip to stay with her. Joan of course insisted that Chatterton leave, that she would carry on bravely alone."

To escape the reporters camped out on her front lawn, Crawford went to Palm Springs with director Howard Hawks, and was later reported to be "in seclusion" at a private Malibu hideaway. It was there, "surrounded by the love and laughter of such good friends as Clifton Webb [he called her "Blessed Joan"], Kay Francis, Ivor Novello, Marlene Dietrich, and Ronald Colman," that Joan recovered, casting aside negative thoughts that she would ever find true love again.

"The kind of love I

do

believe in must exist somewhere," she said, "or the poets would not have glorified it in beautiful music or a sunset."

5

Bette—A Bitch Is Born

"I wanted to be known as an

actress, not necessarily as a star,

although that would be frosting

on the cake if it should happen."

—BETTE DAVIS

W

ithin a week of its release,

Ex-Lady,

Bette's star debut film, was pulled from theaters. "My shame was exceeded only by my fury," she said, responding to critics who denounced her for appearing half-naked in the boudoir scenes.

Undaunted, and still determined to launch her as their resident blond sex symbol, Warner Bros. announced that Bette would costar with William Powell in a glamorous extravaganza called

Fashions of

1934. Set in Manhattan against a plot of fashion piracy (Paris haute couture versus New York ripoffs), it would feature Bette dressed in fifteen "sleek and shimmering Orry-Kelly gowns." Her hair and makeup would be created by Antoine, a Polish hairdresser imported from Paris to work specifically on this picture. 'Antoine is on the way to the Warner's studio in Hollywood," said the New York

Sun,

"there to apply his ideas of hairdressing and makeup, which he declares so powerful a force that it will eventually supersede all methods of conquering fear and acquiring inward strength. Miss Davis fortunately needs neither a change of coiffure nor yet a method of conquering fear."

Antoine and

Fashions of

1934 flopped, but Warner Bros. followed rapidly with

The Big Shakedown,

costarring Charles Farrell. The studio now attempted to establish Bette as part of a popular team. They asked the public to find the perfect leading man for fickle Bette. "Garbo had her Gilbert, Crawford had her Gable, and Gaynor her Farrell," the contest declared, "so let's have your choice. Send us the name of the star you think would be the perfect lover for Miss Davis in forthcoming screen productions."

Bette said she didn't

want

a perfect screen lover, she wanted a good script, which was a rare commodity at Warner Bros. in those days. "Jack Warner seldom invested any large amount of money in scripts," said Joan Blondell. "In the early thirties his motto was 'Let's make them fast, and make them cheap.' He seldom bought [the rights to] books or plays. The scripts for most of those gangster pictures and ninety-minute melodramas were based on remakes or on stories taken from newspaper headlines. I'm not talking against the guys in the story department, but a lot of them were 'idea men.' The quality writers were over at M-G-M or at Paramount."

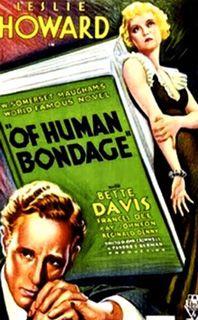

Davis knew that if she were to succeed she would have to resort to the sneaky tactics used by Joan Crawford during her early days at Metro. She could not rely on studio assignments; she would have to hustle and track down her own scripts. When she raided the Warner files and found nothing worthy of her talents, she began to enquire about parts outside the studio. She learned of two scripts, both potential star vehicles, that had been put on hold for the want of a leading actress. The first of these was

Of Human Bondage

at RKO. It would ultimately establish her name and fix her image as "the first consummate bitch in Hollywood history."

"Me? I disgust you? You're too

fine. You cad. You dirty swine, I

never cared for you, not once....

It made me sick when

I let you kiss me ... and after

you kissed I always used to wipe

my mouth!

Wipe my mouth!"

—BETTE DAVIS IN OF

HUMAN BONDAGE

In the fall of 1933, when the script of

Bondage

was submitted to the leading ladies in Hollywood, they stampeded en masse to get away from the character of Mildred, the guttersnipe Cockney waitress. "Any number of actresses who had been approached to play Mildred had turned it down," said the director, John Cromwell. "'Oh God, no,' they would say. 'This would ruin my career, to play a bitch like that.' Then Bette came in and I felt instinctively that she could do it." "I read for Mr. Cromwell," said Bette. "Then I read for Mr. Berman [Pandro S., the producer]. I read for any number of people at RKO, including the mail boy. They all agreed. I was Mildred. However, Mr. Jack Warner, my boss, thought otherwise."

Warner refused to loan her out. He said the part was too vicious, audiences would hate her, it would destroy her career. "What career?" said Davis. "I was playing vapid blondes and silly ingenues. For audiences to hate me, they would first have to

notice

me. I needed a role with guts, and Mildred was

it."

Warner argued that the picture wouldn't make a dime at the box office. He reminded Bette that Joan Crawford had appeared in Somerset Maugham's last film,

Rain,

and it bombed.

"Jack!"

said Bette. "The reason that

Rain

failed with Miss Crawford is because Miss Crawford

cannot

act her way out of a brown paper bag.

I

am an actress, and I will do this picture."

"Let me think about it," said Warner.

While Bette was waiting for Warner to make up his mind to release her, a second project materialized, at Columbia Pictures. Director Frank Capra was looking for the right actress to play the part of a runaway heiress in a film called

Night Bus,

soon to be retitled

It Happened One Night.

The role had been turned down by Constance Bennett, Miriam Hopkins, Myrna Loy, and Margaret Sullavan when writer Robert Riskin suggested Bette Davis to Capra.

"Yes,"

said Davis, "I

was

offered that part.

Before

Miss Colbert. The entire package would have been

heaven.

A good script, a wonderful director, Clark Gable, and

me.

I was absolutely mad about Clark Gable. I admired him

enormously!"

Director Frank Capra requested Bette, and once more Jack Warner refused to release her. "He told Mr. Capra that I was tied up for a

year,"

she said, "which wasn't true at all. He made me do these

asinine

pictures. In one

[Fog over Frisco]

I wound up as a corpse in the trunk of a car; in another

[Jimmy the Gent]

I was a last-minute replacement for Joan Blondell. Why I didn't lose my mind I don't

know.

I was angry, but I was a good girl, a very good girl. I wanted to play Mildred. So I had to be nice to Mr. Warner. I pestered him night and day to release me to RKO. I arrived at his office in the morning with the shoe-shine boy. I was there at night when he left to go home. I begged and pleaded, and after six months he finally said, 'Yes. Go hang yourself!'"

The part was hers, when Bette learned she was pregnant. She would later say her mother and husband persuaded her to have an abortion. The economics and the lost time would hurt her career. "I did as I was told," she stated meekly.

"No compromises," she told

Of Human Bondage's

director, John Cromwell. She understood Mildred's nastiness and evil machinations, and wanted to look physically unattractive in the closing scenes. "No other actress would have dared face a camera with her hair untidy and badly rinsed, her manner vicious and ugly," said Cromwell. "I was not going to die of a dread disease looking as if a deb had missed her nap," said Bette.

In her attack on the role of Mildred, the pyrotechnics of Bette's unique and bizarre style of acting—the bulging eyes, the waving of the arms, and the zigzag walk—came into full force, although her performance was carefully monitored and controlled by her director. Cromwell, who would later direct Kim Stanley in a quintessential study of a neurotic star, Paddy Chayefsky's

The Goddess,

said he sensed a similar desperation in Bette Davis during the making of

Bondage.

"She had been in Hollywood for some time. She wanted success. She craved the big time. She knew Mildred would be her last hope, her final chance, and that desperation can be seen in her performance."

Davis' costar, Leslie Howard, also contributed to her malignant performance. Reporter Vernon Scott said that, during the first days of filming, the English actor and his fellow performers Reginald Denny and Reg Owen would "huddle in a corner and bitch about the American girl playing the part of Mildred." Howard was jealous and indifferent toward her, another reporter stated, and "that indifference, along with the determination to convince him she was his equal, gave an almost maniacal edge to the hatred she conveyed in acting with him."

The night the film was previewed in Hollywood, Bette did not attend. She sent her mother and her husband in her place. When they returned, their faces were blank and they remained silent until Bette begged them to say something. Her husband said she gave a painfully sincere performance, and he doubted if it would do her much good.

On June 28, 1934,

Of Human Bondage

opened at the new Radio City Music Hall in New York City. The audiences became overwrought, bursting into applause when Mildred died, and again when the film was over. "The reviews were

raves,

every single one of them," said the triumphant Bette. "Probably the best performance ever recorded on the screen by a U.S. actress," said

Time.

"Miss Davis will astonish you," said the New York

Daily News.

"The picture was an immense success all over the world," said Bette, "and it brought me my first Academy Award nomination as Best Actress."

"She was

not

nominated as Best Actress for

Of Human Bondage,"

said Joan Crawford in 1973. "Miss Davis keeps perpetuating that myth. It's incorrect. Check the Academy."

The nominees that year were: Claudette Colbert for

It Happened One Night,

Grace Moore for

One Night of Love,

and Norma Shearer for

The Barretts of Wimpole Street.

"There was a

mistake,

a terrible mistake," said Bette. "Inadvertently, my name was left off the nominations list. It caused a

tremendous

uproar. The Academy was forced to ask the voters to write in their own choice on the final ballot."

The voters chose Claudette Colbert for the picture for which Davis had been requested.

"The entire town went for

It Happened One Night,"

she said. "Everyone said it was a cheat. Jack Warner was also against me. He did not want me to come back to Warner's with a swelled head. He sent out instructions to everyone to vote against me. But I made history, of sorts. The next year the entire voting procedure was taken over by the firm of Price, Waterhouse, so the studios could no longer fix the contest."

Bette and Joan—Rivals in Love

Back at Warner Bros., Davis trudged "through the professional swamp, brimming over with tears of frustration and rage." In August 1935 the actress was finally given a script and a leading man that met with her approval. The script was titled

Dangerous.

It was loosely based on another of her idols, Jeanne Eagels, the brilliant, self-destructive actress who died of a morphine overdose at age twenty-nine.

Joyce Heath, her character in

Dangerous,

"was a drunk, not a doper," said Davis. "She was jinxed, self-centered, neurotic. [She cripples her husband in a car wreck on her opening night.] Personally I did not know anyone like her, or like Mildred in

Of Human Bondage;

but I could recognize her ego and devious behavior, from myself and other actresses."

Her leading man was Franchot Tone. A graduate of Cornell, Phi Beta Kappa, Tone came from a wealthy family and was a member of the prestigious Group Theater in New York. He had talent and East Coast breeding, qualities that appealed enormously to Bette. "If the truth be known," she wrote in her memoirs, "I fell in love with Franchot, professionally and privately. Everything about him reflected his elegance, from his name to his manners."

But Franchot Tone was already taken, by none other than Joan Crawford.

When Franchot Tone arrived in Hollywood during the spring of 1933, he told friends he wasn't interested in movie fame, the phony glamour, or superficial parties. He was there for the quick money, to subsidize his Group Theater back east. He intended to take the cash and run, but then he met Joan Crawford.

The two had been introduced before, in New York, when he was the toast of the town, starring on Broadway in

Success Story,

and she was just another visiting Hollywood celebrity. At M-G-M he was on her turf, in her realm, and Joan, in the throes of her "painful" split from Douglas Jr. but still eager for some sophisticated masculine company, summoned Franchot to her home for tea. He obeyed the call because he was working with her at the time, playing her brother in

Today We Live,

and he was curious to find out "if she played the role of the grand-star at home."

Joan did not disappoint the actor. Tea was served from her set of antique silver, complete with scones and a slight English accent. Franchot, for contrast, decided to play along, but from the other side of the tracks. He proceeded to talk dirty, using four-letter words, and Joan, never a slouch when people ridiculed her, laughed, then lowered her demeanor, matching his language, with no restraint on expletives.

Mr. Tone stayed for dinner.

She was fascinated with his background, and he was interested in "the power structure of Hollywood," in which Joan was a leading player. She advised him on his career. She arranged for him to appear with her in a second, then a third picture. She supervised his publicity, ensuring that he be photographed by her favorite, George Hurrell. Interviews were set up for him with her friends. "I don't think that I'd have any publicity if it had not been for Joan," he freely admitted. "Interviewers only wanted to hear about her."

What Bette Davis and her new best friend, Jean Harlow, wanted to know was what the handsome intellectual saw in the glamorous but superficial Crawford. Franchot spoke of Joan's

"intelligence de coeur,"

her intelligence of heart. "She possesses a beautiful mind and spiritual qualities that are going to take her to supreme heights," he said.

He introduced her to the works of Shakespeare, Ibsen, and Shaw. "Sitting on the floor before a great fire in Joan's home, Franchot would read aloud," said writer Jerry Asher. "Joan would listen as she worked on one of her hooked rugs, one foot curled up under her."

"Douglas introduced me to the great plays, and Franchot told me what they

mean,"

said Joan, whose vocabulary was also expanding. "He taught me words like 'metaphor,' and 'transference,'" she said.

"And she taught him words like 'jump,' and 'fuck,'" said Jean Harlow.

"Au contraire,"

Joan could argue: her relationship with Tone was platonic at the outset. "He helped me recover from my soul sickness over Doug," she stated.

The physical consummation of their romance came courtesy of the aforementioned Jean Harlow. Joan never liked Jean. She had "a controlled detestation for the girl," Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., said in his memoirs, also divulging that at dinner one night Harlow rested her hand in his lap while announcing she had just become engaged to Joan's good friend at Metro, Paul Bern. Joan overlooked that indiscretion, but later, when Jean began to make cow eyes at Franchot Tone on the set of

The Girl from Missouri,

the star from Kansas City decided it was time to put her territorial brand on the cultured Eastern actor.

On the day she seduced him, Joan was indulging in her latest passion—sunbathing. "The best sun is between twelve and two," she told the readers of

Motion Picture.

"I give myself an hour on the front of me, an hour on the back and a half hour on each side. Then I feel like a little pig which has been well roasted on a revolving spit." She had a solarium built for isolated pleasure. It was enclosed, at the rear of her house. She was in there, revolving, when Franchot arrived for their afternoon culture session. When he was announced by the butler, Joan called out and asked if he would be a dear and fetch her bottle of special suntan oil ("mineral oil, mixed with spring water, a little cologne, and one drop of iodine"). Franchot brought the bottle and knocked on the door. On cue, it swung open, to reveal his hostess, gloriously tanned, glistening from every pore, and completely nude. She said nothing. Her eyes were closed. She lay on her back listening to his labored breathing. Then, with perfect timing, she arched one leg, opened her eyes, smiled at Tone, and murmured, "Shut the door, darling, and do my back."

Franchot did not emerge from the solarium until nightfall, the neighbors noted.

Not too long after this Crawford had Tone's M-G-M contract extended and renegotiated by her agent, Michael E. Levee. She got him a raise and a bonus of twenty-five thousand dollars, which enabled the actor to move from his bachelor digs in Santa Monica to a more fashionable, convenient residence, close to her in Brentwood. "Their backyards almost touch," said Louella Parsons, who rhapsodized over the decoration of Franchot's house. "In the bedroom," said Parsons, "the chic bedspread of white glazed chintz is set off with red tassels." All of the interiors were designed by William Haines, with a large assist from Joan. "Her touch," said Franchot proudly, "is everywhere." "At the moment, Franchot is Crawford's enthusiasm," said Samuel Richard Mook in

Picture Play.

'And when Joan develops a fondness for a person, said person might as well resign himself to doing nothing else until the fondness has abated—as it always does. She simply smothers you."

Crawford told Jerry Asher that she had no plans to marry Tone. "I do not believe in marriage for two people living in Hollywood," she said. She believed in marriage "the modern way," she told reporter Jimmie Fidler. "You

can

have your cake and eat it. If you nibble at the edges it lasts longer."

Her liberated philosophy would soon be changed, by Bette Davis.

In September 1935 Franchot Tone had just returned to Los Angeles from location shooting on

Mutiny on the Bounty

when he was told by M-G-M that he was being loaned to Warner Bros. to play opposite Bette Davis in

Dangerous.

There was no record of Tone's immediate reaction to this news, except for a column quote a few weeks later in which the actor said that Bette was "a tip-top player to work with." Bette was also complimentary to Tone. "He was a most charming, attractive, top-drawer guy. He really was," she said. During the filming she confessed to Joan Blondell that she had fallen hard for the New York actor. "I was on the lot doing a picture when Bette came to see me, all soft and dewy-eyed, which was

not

her usual manner, believe me. She was in love, she told me, with her leading man, Franchot Tone. I was amused. I thought she was kidding. After all, she was married to that sweet guy, Ham, the musician. And, furthermore, I didn't think she went in for that sort of thing—for soundstage romances. It's not that she was a Holy Mary; she wasn't. Her career always came first. So I kidded with her, saying that we all get crushes on our leading men from time to time and they passed, although I wasn't one to prove it: I married one [Dick Powell]. Bette got very angry with me. She said, 'Joan! I am

not

a schoolgirl. I don't

get

crushes. I am in love with Franchot, and I think he's in love with me.' I said something lame, like 'Give it time, honey,' although I was really thinking, 'Boy! If Joan Crawford gets wind of this, there is going to be

war.'"

Adela Rogers St. Johns was at Warner Bros. during the making of

Dangerous.

"I didn't know Davis too well," she said, "but I knew she had a reputation for being tough on her leading men. She hauled off and socked Charlie Farrell over some minor misunderstanding on one picture, and Jimmy Cagney got the brunt of her temper on another. So, when

Dangerous

began and the reports went out that Bette was behaving like a little lamb with Franchot, I suspected something was up."

Davis and Tone held frequent meetings in her dressing room. The actress explained he was a serious artist and she needed his input on her character. "Playing an actress," she said at the time, "is unlike playing an ordinary woman. All her gestures are a little too broad, all her emotions a little too threatening. Her greed, her insatiable zest for living, her all-encompassing ego make her seem completely pagan, but an articulate pagan, one who knows all the tricks of the trade."

Bette Davis and Franchot Tone, working in Dangerous

Joan and Franchot in "No More Ladies"

During the making of

Dangerous,

Joan Crawford suddenly announced her engagement to Franchot Tone. There were no immediate plans for marriage, she repeated: "Marriage makes lovers just people." Her relationship with Franchot was one of utter freedom—although, according to Bette, Joan kept Tone on a short leash throughout the filming. "They met for lunch each day," she said in 1987. "After lunch he would return to the set, his face covered with lipstick. He made sure we all knew it was Crawford's lipstick. He was very honored that this great star was in love with him. I was jealous, of course."

But not beaten. She appealed to Franchot's actor's ego. She had Laird Doyle, the writer of

Dangerous,

add new material to his scenes with her. This of course necessitated additional rehearsals, and more private meetings with her. "She almost drove herself crazy, scheming on how to get Franchot away from Joan," said Adela Rogers St. Johns, who eventually carried the news of Bette's romantic interest to Crawford.

"Oh," said Joan, when told of the competition, "that coarse little thing doesn't stand a chance with Franchot."

"I mentioned that Bette was a fine actress," said St. Johns, "and was going to become a big, big star."

The latter news apparently intrigued Crawford. She called Adela a few mornings later and asked the writer if she would accompany her to the set of

Dangerous.

"To my knowledge," said St. Johns, "this was the first time Bette and Joan had been formally introduced."