Bette and Joan The Divine Feud (10 page)

6

Joan Tone

"Even in her bath, Joan

Crawford looked as if she were

about to make a public

appearance, just in case a crowd

happened to drop by."

—RADlE HARRIS

I

n December 1936, while Bette Davis was attempting to rebuild her film career, Joan Crawford for the third year in a row was named the Top Box Office Star in America. In February 1937 she was named the first Queen of the Movies by

Life

magazine. On the set of her latest M-G-M film,

Love on the Run,

the fans of

Motion Picture

magazine were given an inside look at the royal treatment bestowed on their favorite. "She appeared wearing a billowing organdy gown," said the magazine. "Two handmaidens held the dress up so the flounces would not get dirty. One girl got her a chair. Another turned an electric fan on her. Another brought her phonograph and started playing sweet music for her. The Queen was very gracious." She was joined by her husband, Franchot Tone—"full of a superiority complex"—who advised her to stop the interview. ''A rug was unrolled from where they were standing, to the door of Joan's portable dressing-room," said the magazine. "Mr. and Mrs. Tone strolled along the rug and disappeared into the dressing-room, never to be seen again."

"Joan Crawford is never the movie star in the presence of the truly great," said Katharine Albert. "The renowned conductor Leopold Stokowski has been a visitor to her home. Before him, Joan stands in real awe. And once, when she saw Albert Einstein walking on Fifth Avenue, she was speechless."

Writer Dale Eunson, who was married to Katharine Albert, spoke about the roles they played in the creation of Joan Crawford. "We had both worked with Joan from the beginning of her career," he said. "I worked in publicity and Katharine wrote for

Photoplay

and

Modern Screen.

Katharine was largely responsible for teaching Joan how to handle the press. She coached her, told her what to say and how to make friends of interviewers."

At one time, when the Eunsons lived in Connecticut, Joan called with an emergency. She was getting a divorce. She asked if Katharine would meet her train in Chicago, to brief her on what to say to the reporters in New York. Dale Eunson, who would later write a film

(The Star),

patterned on Joan and played by Bette, commented on the differences between the two. "Joan was not too intelligent. She wasn't half as smart or as talented as Bette Davis. But Joan developed charm, a wonderful charisma. She knew how to manipulate people with her looks and personality. She was an actress after all, even though later on she often got confused as to what role she was playing in her own life."

In her life as Mrs. Franchot Tone, the metamorphosis began right after the wedding. Following their honeymoon in New York, the couple returned to L.A., to reside at Joan's home in Brentwood. "Hello, tree; hello, house—I'm home again," said the happy bride, who proceeded to wipe out every trace of EI JoDo by gutting the interior of the house she had shared with Fairbanks, Jr. She changed the decor to Spanish Modern, which captivated Louella Parsons, who said she was enraptured with "the two mechanical doves that kissed over the doorway everytime the doorbell rang." There was a new music room, with a false wall built to hide the original stained-glass windows. At the rear of the house, the star told Louella, she had installed a formal rose garden and a special area where her beloved dogs could "do their business" away from the main area.

In

Liberty

magazine, Katharine Albert provided an intimate glimpse of Mrs. Tone at home, preparing for one of her intimate dinner parties. "In her bedroom," wrote Albert, "after badminton, as expert fingers arrange the crisp chestnut curls, Joan reads the most important fan mail, sent by her secretary at the studio. The downstairs maid then appears, asking Madame to put her final approval on that evening's menu. 'Clear soup, stuffed lobster, duck and wild rice, endive and chive salad, hot cherries in ice rings—white wine with the fish, champagne with the fowl, coffee, and Napoleon brandy.'

"'Check,' says Joan.

"The butler then enters. Will Madame select the program for tonight's film showing? Joan selects a newsreel, a Mickey Mouse cartoon, and an unreleased Metro feature."

In

Carnival Nights in Hollywood,

writer Elizabeth Wilson gave the next installment: the impressive guest-list and Joan's entrance. "The guests are all assembled before Joan appears, pausing first at the top of the stairs. She has the best tan, Barbara Stanwyck the worst (busy working days on

Stella Dallas).

While long and lean Gary Cooper plays with the marble machine in the game room, challenging Una Merkel and Charles Boyer to a game, Cooper's lovely wife, Sandra, talks to Betty Furness and Pat Boyer. Luise Rainer and her husband, Clifford Odets, arrive, and Franchot Tone instantly goes into a huddle with Odets. The two know each other from New York. As Ginger Rogers eyes the food, Robert Taylor and his girlfriend, Barbara Stanwyck, who suffers the torture of the timid, play ping-pong, while Joan Crawford looks on holding a little glass of sherry, which she never touches. She seldom drinks, Joan explains, 'it makes me cry.' Although a grave girl, bordering on the intense, Miss Crawford always surrounds herself with gay, amusing people. And at the first sound of laughter from her guests Joan snaps out of whatever depressing mood she may be in, and quickly becomes the gayest of the gay."

The Fight for Scarlett O'Hara

"It was insanity that I not be

given Scarlett. The book could

have been written for me. I was

perfect for Scarlett, as Clark

Gable was for Rhett."

—BETTE DAVIS

According to Bette Davis, there was never any professional rivalry between her and Joan Crawford. "Don't be

ridiculous!"

she admonished this writer when asked if the two were ever up for the same role. "We were two different types

entirely.

I can't think of a single part I played that Joan could do. Not one. Can you?"

In the summer of 1937 Davis and Crawford were in the running for one role, that of Scarlett O'Hara in

Gone with the Wind.

The book had been purchased for her, Davis claimed. "Before I rebelled and went to England, Jack Warner told me he had bought a wonderful book for

me—Gone with the Wind.

'I bet it's a

pip,'

I answered and walked out."

"That story is just another of Miss Davis' fantasies," said Joan Crawford.

"Gone with the Wind

was never bought for her by Warner's. I should know, because my studio, M-G-M, made the picture, and I was the first to be mentioned for the role."

According to director George Cukor, who worked for two years on the casting of the film, Warner Bros. was asked to bid on the book. "They turned it down," said Cukor. "Jack Warner would not pay the money. Nor would L. B. Mayer. It was David Selznick who put up the fifty thousand dollars for the film rights. When the book became a big success, selling over a million copies in six months, every studio in Hollywood wanted to make the movie, and every actress between the ages of thirteen and sixty-two wanted to play Scarlett O'Hara."

L. B. Mayer was the first to approach producer Selznick with a package deal. He offered Clark Gable as Rhett Butler, Joan Crawford as Scarlett, Maureen O'Sullivan as Melanie, and Melvyn Douglas as Ashley Wilkes. "Selznick said he would have to think about that," said author Gavin Lambert.

While thinking, Selznick spoke to Samuel Goldwyn, who refused to loan out Gary Cooper for Rhett. Then the producer thought of Errol Flynn. "It was Flynn that prompted Selznick to talk to Jack Warner," said George Cukor. "Bette Davis was thrown in as part of the deal."

Selznick told Warner he would like time to ponder that package too, but in the meantime, with the help of press agent Russell Birdwell, he launched his nationwide door-to-door Scarlett O'Hara talent contest. "That was pure hype, said Cukor. "Selznick had no intention of choosing some unknown for the part. Why should he, when he had the entire female contingent in Hollywood climbing in his window and scratching at his door, begging to play Scarlett?"

Norma Shearer had the part, it was reported, but she gave it up when her fans wrote in and begged her not to play such an unsavory character.

In a preliminary poll, radio columnist Jimmie Fidler put Bette Davis as number four for Scarlett, with Joan Crawford in fifth place.

"Thousands of people wrote in and said I would make a wonderful Scarlett, with Clark Gable as Rhett Butler," said Joan. "Clark and I were a team at that time, having done five or six pictures together. He and I spoke about the book a few times. This was long before he was signed as Rhett. He had some reservations about doing the role, which were foolish, because whatever doubts the people had on who should play Scarlett, everyone agreed that only Gable should play Rhett Butler."

Crawford, at Mayer's request, went to see David Selznick. "David and I had made

Dancing Lady

together, with Clark Gable, a few years before. It was one of Metro's biggest grossers that year. He and I had a long talk about Scarlett, but I never tested for the role. David seemed to feel I was 'too modern' for the part, and I tended to agree with him. He asked me who I thought should play Scarlett. I told him, 'Katharine Hepburn would be wonderful, if you could get her.'"

Katharine Hepburn wanted the role. She said she was the choice of the author, Margaret Mitchell. But when Selznick asked her to test, she refused. "You know what I look like, David," Hepburn told the producer. "Yes," he said, "and I can't imagine Clark Gable chasing you for ten years." "Damn you!" said Miss Kate, and that was the end of her bid for Scarlett.

As sales of the book escalated worldwide, the name of Bette Davis began to emerge as the people's choice. "She was easily the most popular candidate, with forty percent of the vote," said Gavin Lambert. "There were as many people against Bette Davis as there were for her—maybe more," said David Selznick, who spoke to Jack Warner again. Warner renewed his package offer of Errol Flynn for Rhett Butler, Bette for Scarlett, with Olivia de Havilland included as Melanie Wilkes. "I

refused

to be part of that parcel," said Bette. "I wanted to do Scarlett very much, but Errol Flynn was all wrong for the part of Rhett. Gable was

perfect.

I would have done anything to play with him. I was also told at the time that Mr. Gable was very much in favor of my playing Scarlett."

"Clark was not even

remotely

interested in having Bette Davis as his costar in

Gone with the Wind,"

said Joan Crawford in 1973. "I know that for a

fact."

"Gable and Bette Davis? I can't honestly recall if that pairing was ever seriously considered," said George Cukor.

"Mr. Cukor put thumbs down on me," said Bette, referring to ancient grievances between the two from their early days in Rochester repertory, when he fired her without proper cause.

"She tells that story repeatedly," said Cukor, "knowing full well that the decision was not mine but Mr. Selznick's. Certainly Bette had the talent and the temperament to play Scarlett. But in terms of physical type, Joan [Crawford], with her auburn hair and blue eyes, was closer to the heroine Miss Mitchell wrote about. Still, with due respect to both ladies, I don't believe the film would have worked as well with either one. The choice of Vivien Leigh as Scarlett was impeccable.

Gone with the Wind

would not have become the classic it is today with Bette Davis or with Joan Crawford."

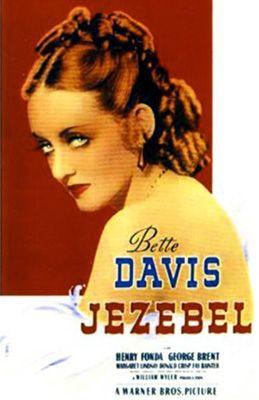

"They called her JEZEBEL—the

Heartless Siren of the South. She

asked all, took all, gave

nothing."

—AD FOR

JEZEBEL

In the fall of 1937, while Metro continued its search for Scarlett O'Hara, Jack Warner had already embarked on his plan "to steal the wind from producer Selznick's sails." On October 5, Warner announced that he was going to produce his own Southern saga,

Jezebel;

and to play the leading role of Julie Marsden, the high-spirited imperious vixen of Louisiana, he chose Bette Davis.

"A drama of moss-hung New Orleans,"

Jezebel

surfaced on Broadway in 1934, starring Miriam Hopkins. It ran for forty-four performances, then closed. The film rights had been offered to various studios, including Warner Bros. In a February 1935 memo, assistant producer Hal Wallis recommended that they buy the rights. "Bette could play the spots off the part of a little bitch of an aristocratic Southern girl" Wallis stated. But Jack Warner said audiences would never warm to such a rebellious, independent woman, and the story was rejected.

In 1936, when Scarlett O'Hara and the success of the

Gone with the Wind

novel captured the attention of the world, Jack Warner quietly began negotiations for

Jezebel.

In January of 1937, he bought the rights for twelve thousand dollars and told Davis she could have the leading role. "I am thrilled to death about

Jezebel,

" Bette said in a note to Warner. "I think it can be as great if not greater than

Gone with the Wind.

Thank you for buying it."

The budget for the film, $780,000, certainly matched Metro's plush mountings, and also pleased Bette. Michael Curtiz was assigned to direct, then withdrew, preferring instead to work with Errol Flynn on the more expensive $1.6-million production of

The Adventures of Robin Hood.

In his place, director William Wyler was borrowed from Samuel Goldwyn, and at Wyler's urging, his friend and houseguest, aspiring filmmaker John Huston, was hired to rewrite the script.

Early in October 1937, with a "No Visitors" sign on the soundstage door, cinematographer Ernest Haller tested Bette Davis in color for

Jezebel.

Her skin appeared "too pasty," and her lips a "terrible orange." "Technicolor makes me look like death warmed over," said Bette. It was decided to shoot the film in black and white with Haller (who, along with

Jezebel

composer Max Steiner, would later work on

Gone with the Wind).

To provide an authentic Southern accent, Bette was coached by a philosophy professor from Louisiana State University, who also supervised the plans for the sets. Her period wardrobe was designed by Orry-Kelly. The idea for the scandalous red dress, worn by Bette at the all-white Olympus Ball in 1850, was said to have been inspired by a real-life incident from 1936. At the Mayfair Ball that year, hostess Carole Lombard requested that her female guests wear formal gowns of snowy white. Making a late entrance was Norma Shearer wearing a spectacular scarlet gown. Witnessing her arrival was John Huston, who reportedly inserted the scene during his revisions of the

Jezebel

script. Embellishments to the character of Julie Marsden were added by Bette and director Wyler. For the opening scene, where she jumps off her horse and strides into her mansion, she practiced at home with a riding crop, cracking the whip as "her husband and dogs scurried outdoors." Her actions had to be perfect, she explained. "In the scene, as Julie enters her house, she lifts the skirt of her riding outfit with the leather crop. It establishes her character in one gesture."

Bette makes her points to director William Wyler, as co-star Henry Fonda listens.

On October 25 production began on

]ezebel.

Wyler, tireless and ruthlessly blunt, was described by actress Myrna Loy

(The Best Years of Our Lives)

as a sadist. "He liked to wear people down, by the number of takes," said Loy. For the opening shot in

Jezebel,

he made Bette Davis repeat the riding-crop scene forty-five times. She had too much energy, he told her. Her gestures were too broad, too theatrical. "Do you want me to put a chain around your neck? Stop moving your head," he cautioned her.

In a room of his Beverly Hills home, Wyler had twenty-eight miniatures of the film erected. Each evening after dinner he would place the set he was going to work on the next day in the middle of the dining-room table. With a miniature toy camera and miniature actors, he would plan his shots while Bette or John Huston spoke the actual lines in the background. Each scene would be repeated, timed with a stopwatch. The following day variations would be added in rehearsals, and then the endless retakes would begin.

"He was a perfectionist and had the courage of twenty," said Bette, who was pleased by her controlled performance and by the knowledge that she had at last found her creative and emotional match in a man. Wyler, attracted to volatile actresses (including Miriam Hopkins and Margaret Sullavan, whom he married), began a clandestine affair with Davis, which gave the master director the upper hand in dealing with the tempestuous Bette.

The Olympus Ball scene, where the defiant Julie Marsden was forced to dance in her red dress before a shocked virgin-white assembly, took one week to shoot. The estimated distance covered in the endless waltz came to thirty-six miles. Her costar Henry Fonda added to her angst, said Bette.