Bette and Joan The Divine Feud (11 page)

The role of Jezebel's fiancé had been initially offered to Franchot Tone. He was Bette's first choice, but she was told he was booked solid at M-G-M, playing backup to Joan Crawford. William Wyler wanted Henry Fonda, who refused the offer. His wife was pregnant in New York, and he wanted to be at her side when the baby was delivered in early December. Wyler assured Fonda his scenes would be photographed in time for him to be released for the birth of his first child (Jane). "Every time I see her face, I think of the hell she put me through on

Jezebel,"

said Bette later.

Throughout December and into January, while Jack Warner howled about the costs of retakes and overtime, director Wyler held steadfast to his creative standards. Bette complained too, but not to Wyler. Wearing slacks under her crinolines, she filmed the final night scenes in a swamp set up on the back lot. The action called for her to wade through the swamp and dart past a roadblock to eventually reach the bedside of her plague-stricken lover. After the scene was shot five times, Wyler said he was not satisfied with the appearance of cold, damp Bette. "She looks like she merely stepped in a puddle," he stated. Grabbing a shovel of wet mud, he threw it at the actress. "Now we're in business," the director said.

On January 27, 1938, five weeks over schedule and $250,000 over budget,

Jezebel

was completed. That night Bette took to her bed, suffering from bronchitis and nervous exhaustion.

On March 3 the film was screened in Hollywood, with David Selznick in attendance. That night he sent Jack Warner a telegram, stating: "The picture is permeated with characterizations, attitudes and scenes which resemble

Gone with the Wind."

Warner replied with a cable of his own, thanking the producer for his "splendid interest"; a week later

Jezebel

opened at the Radio City Music Hall in New York City. Calling Bette "one of the wonders of Hollywood," the National Board of Review deemed her performance as Julie Marsden to be "the peak of her accomplishments." Described as "Popeye the magnificent," she appeared two weeks later on the cover of

Time.

The film had "things that smacked of

Gone with the Wind,"

the magazine said, predicting that it could slow Mr. Selznick's epic down to a breeze, and that the only one who might play Scarlett O'Hara after Bette Davis' performance was Mr. Paul Muni.

"A cheap shot!" said Bette, preferring to ignore all comparison between her Julie and Scarlett O'Hara. Author Margaret Mitchell seemed to agree. "I liked it

[Jezebel]

so much, but have found so few people who agree with me," said Mitchell. "I did not see similarities between it and

Gone with the Wind,

except for costumes and certain dialogue, but I do not feel I have a copyright on hoop skirts or hot-blooded Southerners."

With the success of

Jezebel,

and befitting her stature, at last, as a bona-fide Hollywood star, Bette moved into a rented estate in Coldwater Canyon, "with tennis court, swimming pool, wide sunny patio and porches and plenty of room for the household schnauzers." During that summer it was announced she would play Judith Traherne, the tragic heroine in

Dark Victory.

After playing three bitches in a row, Bette said she was "desperate to play a sympathetic character." Budgeted at two million dollars, the studio announced that every effort would be made to add authenticity to the character of the rich, indulgent society girl who finds peace and humility when she discovers she is dying from brain cancer. In her column, Louella Parsons reported that the studio had telephoned London, to see if Dr. Sigmund Freud, "probably the greatest psychoanalyst alive," would come to Burbank to act as technical adviser on the film. (It is not known if Freud responded.)

Bette was also pleased when she was told that she could have the leading man of her choice, Spencer Tracy. She and Tracy shared the same birthday, April 5. Consummate professionals, dedicated to the craft of acting, they had worked together once before, in

20,000 Years in Sing Sing,

in 1933. He had been "fascinated by her odd unpredictable gaiety." She was attracted to his Irish looks and intensity. Spencer told her then, "You know, you could be the best actress in pictures today. No, I'll correct that. You

are

the most talented." "Damn right," Bette agreed: "But who are we against so many?"

She longed to work with the actor again.

Dark Victory

was to be that script. But when producer Hal Wallis tried to borrow him from M-G-M, the answer came back that Tracy was unavailable. He was taken, professionally and privately, by Joan Crawford, which would later lead Bette to comment acidly, "She slept with every male star at M-G-M except Lassie."

Joan's Sex Life

"Joan and I began at Metro

together. She was such a pretty

girl. All of the men wanted to

[bleep] her. And most of them did."

—A FELLOW M-G-M ACTRESS

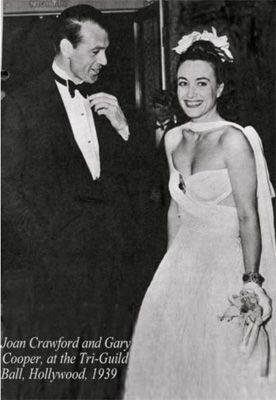

Joan Crawford was never a hypocrite about sex. "I like it," she said, "and it likes me." Her physical conquests, like Catherine the Great's, were said to be in the thousands, not counting repeats.

In Hollywood in the late 1920s, when Joan became a star, many Hollywood women resented her, not only because she slept with their husbands and boyfriends, but because she "was better in bed than they were." Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., always a snazzy dresser, was halfway home, it was said, after his first night with Joan, when he realized he was barefoot. "We were in heat all the time," said Joan, referring to the first year of their marriage. Then Clark Gable caught her physical attention. He, like Joan, could be "savage in his lust," although in later years she told friends she preferred to distract him from the bedroom because he "wasn't too hot in the sack." ("Pa

was

a lousy lover," his delectable wife, Carole Lombard, agreed.)

"Thank God I'm in love again," said Joan when she met Franchot Tone. "Now I can do it for love and not my complexion." Tone, it was said, had lots of East Coast culture, but only the basic sexual expertise; exchanges were made. "He gave her class and she gave him ass, and Tone never went home again," was a popular rhyme of the time.

Crawford had an X-rated imagination, actress Joan Fontaine believed. Fontaine had a small role in No

More Ladies

in 1935. She recalled one afternoon when the famous Russian actor Ivan Lebedeff paid a call on the star in her dressing room. "In ten minutes Ivan came pelting out, white of face," said Fontaine. "He rushed over to me. In shock, he blurted out, 'Poor Joan! She's just told me that after her tragic life with men, she can no longer find sexual satisfaction unless she is tied to a bedpost and whipped!' "

Fontaine said she chuckled, knowing that Joan was inspired by a recent book,

Psychopathia Sexualis.

Crawford was true to Franchot Tone in the Hollywood sense of fidelity, which meant that during the production of a movie she could, in the interest of art, surrender herself emotionally and physically to her leading man, or, if it led to better work, to her director or producer. The latter included Joseph L. Mankiewicz, a writer and producer of many Crawford films in the late 1930s. Mankiewicz, who was responsible for some classic W. C. Fields repartee, including "my little chickadee," first captured Joan's unbridled glee when, reading from his script, he came to the line: "I could build a fire by rubbing two boy scouts together." It was his youth, charm, and intellect, and his ease in handling capricious actresses that led to his producing six of Joan's films, some of them terrible bombs. "She did what she was told," he informed this writer. He made her feel relaxed, Joan claimed: "I was madly in love with him and it was lovely. He gave me such a feeling of security, I felt I could do anything in the world."

It was Joe Mankiewicz who introduced Crawford to his former college roommate Spencer Tracy. The actor, not yet a star, was cast second to Joan in

Mannequin,

a teary tale of a girl from the Lower East Side (Crawford, with an Upper East Side accent) who falls in love with a rich industrialist, played by Tracy. To him the assignment was just another job and Crawford another glamour dame from Metro's assembly line of stars. True to her tradition of hyperbole, she was far more effusive in her remarks on her current costar. "He is the finest actor out here," she told one reporter. "Everything he does is effortless. I'll certainly have to work hard to keep up with him."

During the filming it was Tracy who had to work hard, to keep Crawford from heisting the film. Describing her as "cold-hearted ... a high-class thief," he said he never saw "anyone steal as many scenes as she." Soon he was enjoying the challenge of upstaging and ribbing her. He told her his favorite actresses were Luise Rainer and Bette Davis. While she fussed with her hair in between setups, he cautioned her: "Don't bother combing your hair, dearie. Nobody is going to look at it anyway." Offstage, while she was being made up for their kissing scenes, he chomped on an onion; in their close-ups he stood on her toes.

Joan of course retaliated. She called him "Slug" and "a shanty mick." One day, when he was filming, she had his trailer decorated with colored lights. "A tribute to your ego," she told him. She had "spunk," Tracy declared.

During the filming of

Mannequin,

Joan came down with pneumonia. When she recovered, at the suggestion of her doctor she visited the Riviera Country Club, "for the fresh air." Among the polo players at the club was Spencer Tracy, who helped Joan overcome her fear of horses. He gave her riding lessons. She bought a horse and named him Secret, the status of their affair in full sprint at this time. Tracy, a Catholic theology major, was said to be "besotted" with the more sexually aggressive and experienced Joan. They met on the sly (he was married too), at the studio, the club, and at a friend's ranch in the Valley. When

Mannequin

was completed, they performed on radio together, and Tracy was set for Joan's next film,

The Shining Hour.

But during the hiatus Tracy started to drink, and the affair turned sour.

"Sober, he was a giant," she said. "Drunk, he was vicious, ugly, and

mean."

He lashed out at her acting and ridiculed her attention to "the phony-baloney stuff," such as posing and signing autographs for fans. "She likes to have them follow her when she goes shopping," mocked Spencer. He unnerved her so while riding at the club one day that she pulled sharply on her horse. Secret stopped short and Joan somersaulted over his head, landing on her derriere. "No horse could do that to me," said Joan. "I climbed back on and rode for forty minutes. The next day I rode him again for half an hour. Then I said to the trainer, 'Okay, now you can sell him.'"

That night she gave Tracy an ultimatum. He had a choice: it was her or the booze. Tracy went for the ninety-proof. The next day she called Joe Mankiewicz and told him Tracy was out of her next film. He was now free to go to Warner's, to make

Dark Victory

with Bette Davis. But Spencer declined this assignment. He said he needed a break from "screwy actresses" and went instead to Twentieth-Century Fox to work with the all-male cast of

Northwest Passage.

Bette's Sex Life

"Sex was God's joke on human beings," said Bette Davis in her memoirs, which led Joan Crawford to suggest, "I think the joke's on her."

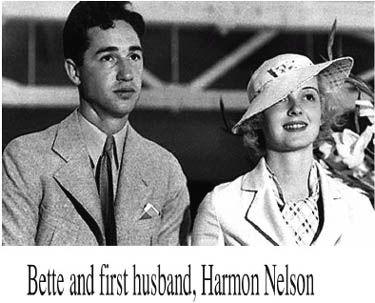

When it came to her private life, Bette, unlike Joan, preferred to keep the important details away from the press. She had been married for four years before most of the public even knew her husband's name. He was Harmon (Ham) O. Nelson and the two had met during her school years at Cushing Academy. Tall and quiet, he had worked as a musician in New York while indulging in an ardent correspondence with Bette. In August of 1932, on one of his visits to Los Angeles, her mother pushed for a wedding.

"I was too high-strung from too much work and no play," said Bette, "so Mother insisted I marry Ham and lose my virginity."

Accompanied by her mother, the couple drove to Yuma, Arizona, and were married by a justice of the peace. After the ceremony they drove right back to L.A. That night (without her mother), in a hotel at the beach, Bette had her first sexual experience. She compared it to "a powerful drug," and was so impressed with the naked male body, she later conferred her groom's middle name, Oscar, on Hollywood's highest honor, the Academy Award, which had a rear end similar to her husband's, said Bette.

There were frequent separations for Bette and Ham during the first years of their marriage. While he pursued a career on the road, playing in big bands, she continued her quest for stardom in Hollywood. In his absence she developed an active sexual fantasy life, which led to some heady crushes on her leading men, including George Brent, Leslie Howard ("The only leading lady who didn't sleep with my husband was Bette Davis," said a presumably grateful Mrs. Howard), and Franchot Tone. The latter, like Gable and Spencer Tracy, had already been taken by Joan Crawford, which led Adela Rogers St. Johns to later comment, "Bette had the fantasies, while Joan had the actual physical goods in her bed. It's no wonder she despised her."

Bette's affair with William Wyler was said to be her first official extramarital excursion. Her marriage to Ham was in trouble at the time. She had grown to loathe the qualities in him she once loved. His career kept him on the road, when she needed him at home. When he stayed at home, playing in an orchestra at the Hollywood Hotel, she asked him why he wasn't on the road, becoming a popular success like Benny Goodman or Harry James. Ham was deep and silent, a New England man, which is why she had married him. But no"" as a working star, when she came home from the studio "ready to explode," he didn't seem to comprehend the hell she was going through—which made her scream all the more.

With those odds, it was no wonder, when the director of

Jezebel,

William Wyler, bullied and pushed and challenged Bette Davis, that she fell madly in love with him. "It was a time of intense work and intense passion," she said. "My life would never be the same again."

Throughout the summer of 1938, as

Jezebel

continued to bring in fresh acclaim for Davis, her affair with William Wyler continued. She said he wanted to marry her. She was apprehensive. Unlike "poor weak Ham," Wyler was capable of controlling not only her will but the most important thing in life—her work. "I was afraid his domination would affect my career," she said. "He was capable of taking complete charge, and I was petrified. The relationship was tempestuous to the point of madness, and I resisted the loss of my sovereignty to the end."

The actress would later tell her daughter she had another reason for not marrying the director. "Her biggest concern was that Wyler was Jewish," said B.D. Hyman. "She didn't want children who had a Jewish father. When I married my husband, that was one of her loudest objections."

Her eventual break with Wyler came that September, said Bette. He wrote her a letter. It contained an ultimatum. If she didn't marry him then and there, he intended to wed another the following Wednesday. Bette, smarting from her last fight with the director, did not open the letter until a week later. As she read the letter, an announcement came over the radio. That morning in Los Angeles, William Wyler had married Margaret Tallichet, a beautiful young actress he had met five weeks earlier. Naturally, Bette burst into tears. She was unable to return to the studio for several days. She refused to see anyone. "She realized that not opening the letter was the most serious mistake of her life," said author Charles Higham. "It is extraordinary to reflect that her next picture with Wyler was ...

The Letter."

A heartbreaking story, that's for sure, but, according to fresh sources, some important details were left out. First, "Willie never married on the rebound," said a friend of the director. "He was madly in love with Margaret Tallichet and stayed married to her for forty years." Second, Bette's passion was already transferred to another, and that was the legendary Lochinvar of the Hollywood skies and bedrooms, Howard Hughes.