Bette and Joan The Divine Feud (5 page)

"I am willing to share her with thousands of girls and boys who adore her almost as much as I do," said Doug Jr.

"Oh darling, you embarrass me," said the blushing Joan.

Upon their return to California, the couple resided at Joan's Brentwood home, redecorated from "early nothing" to Spanish Modem and rechristened El JoDo, an amalgamation of their names, similar to Pickfair. But sanction from the latter estate did not come until three months after their wedding. "The only reason we were eventually invited," said Joan, "was because the fan magazines were ganging up on Mary Pickford, saying how rotten she was to poor Cinderella Joan Crawford."

When the coveted invitation arrived, to a dinner honoring Lord and Lady Mountbatten, Joan spent three hundred dollars on her white Belgian-lace dress, matching bag, and white silk shoes. Driving up to Pickfair that night, she timed their arrival carefully. As she entered the foyer of the blazing house, she could see the guests assembled below in the drawing room. The butler took her wrap, she approached the steps, then whispered "Wait!" to Doug. From below she could see Doug Sr. stepping forward to greet his new daughter-in-law "I think the strap of my shoe has become undone," said Joan.

"Welcome to Pickfair, Joan," said Doug Sr.

"My shoe, it's undone," gasped Joan.

And as Doug Jr., assisted by Doug Sr., bent down to fasten her shoe, Joan's eyes swept down on the crowd all fixed in her direction, until she found herself looking into the ice-cold blue gaze of her hostess, little Mary Pickford. Only then, with the lord

and

young lad of the manor literally kneeling at her feet, did Billie Cassin feel relaxed. She raised her head higher and smiled in Miss Pickford's direction.

"What a great triumph for Joan," said the editor of the Hollywood

Tatler,

commenting on the acceptance of Crawford into the Pickfair family. "She did it without acting, without pretense, she did it by being herself, by proving she wasn't the wild, reckless creature that gossips had painted her."

3

Bette Arrives in Hollywood

I

n November 1930, while Joan Crawford was being hailed as the most luminous new star on the Hollywood horizon, Bette Davis was auditioning for her second screen test in New York. She passed this one and was offered a six-month contract, albeit with a minor studio, Universal Pictures.

On the morning of December 13, after spending five days traveling by train, she and her mother, Ruthie, arrived in Los Angeles. The weather was hot, the people unfriendly, and the oft-told tale of her nonreception unfolded. There was no one on hand to meet them at the station. When she called the studio from her hotel room, she was told that their representative had failed to recognize her at the station, whereupon Bette issued her first Hollywood dictum. "You should have known I was an actress," she said, "because I was carrying a dog."

At Universal, when Carl Laemmle, Jr., the titular head of the studio, got his first glimpse of Bette, he too seemed unimpressed. "He took one look at me through the open door of his father's office, then closed the door," she said. Hollywood was a town of reigning beauties, and she "had as much glamour as a grape." In the photo studio, when asked to raise her skirt to show her legs, Bette snapped, "What has legs got to do with acting?" Rejected for two chosen films, she was put to work as a "test girl," a prop for auditioning actors. Wearing a low-cut gown, she sat on a divan while fifteen men entered the room consecutively, seized her in their arms, and murmured, "You gorgeous divine darling, I adore you, I worship you. I must possess you." Then they proceeded to make ardent love, lying on top of her. "I remained patient," the serious young Broadway actress declared. "This was not the graveyard of my dreams, but just a valley I must suffer."

Making her debut as the second female lead in a B picture entitled

Bad Sister,

Bette was introduced to the state of the art in making motion pictures, 1930s style. For her first scene, a microphone was stuck between her breasts. To avoid static, she was told not to move; every time she turned her head the sound faded, to boom again when she faced front. At a sneak preview of

Bad Sister,

she and her mother sat in the back row of the theater. They cringed as they watched her performance. "My looks, my acting, everything was pitiful." When the final credits rolled, they slipped out of their seats before the lights came up. Embracing each other on the bus back to their rented bungalow, the two wept "copious tears."

To her amazement, after the release of

Bad Sister

Universal picked up her option, extending her contract for another six months. She appeared in minor "goodie-goodie" roles in

Seed

and

Waterloo Bridge.

That September her first full-page photograph appeared in

Silver Screen,

captioned, "Little Bette Davis, of the drooping eyelids and sullen mouth, is only nineteen" (she was twenty-one); Louella Parsons, as Hollywood's leading gossip columnist, noted that Bette gave a good performance in

Seed,

and might have a chance if she put herself in the hands of a capable makeup man. "I was not disturbed by her over-beaded eyelashes and an over-rouged mouth," said Louella.

Determined to be a success in pictures, Davis became avid in her study of the technique of motion-picture acting. She spent evenings and weekends at Pantages and Grauman's Chinese Theater, on Hollywood Boulevard, studying the films of others. Formative influences were Greta Garbo and Ruth Chatterton, but not Joan Crawford. "This was the period," said Bette in her memoirs, "when Joan would start every film as a factory worker. She punched the clock in a simple, black Molyneaux, with white piping (someone's idea of poverty), and ended up marrying the boss, who now allowed her to deck herself out in tremendous buttons, cuffs, and shoes with bows (someone's idea of wealth). The change of coiffure with each outfit kept Joan so busy it was a wonder she had time to forward the plot." (Years later, when Crawford was cited as being a major influence on the fashions of the 1930s and the 1940s, Davis growled, "What in the hell did she ever contribute to fashion—except those goddamned shoulder pads and those tacky fuck-me shoes?")

Aching for a little more glamour herself, when she was loaned out to RKO Pictures for

Way Back Home

in 1931, Bette picked up some beauty secrets from makeup artist Ern Westmore (whose brother Perc worked on Joan Crawford early in her career, contouring her wide, generous mouth, and de-banging her hair). Ern made Bette's small mouth larger, "extending the length of the lower lip, making it slightly heavier to correspond with the upper lip." Her best feature was her eyes, she said, "but now with my new lips and hair my face suddenly seemed to come together. I began to think I was rather beautiful, even if I wasn't."

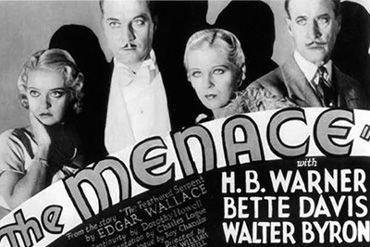

Cosmetically transformed, Bette was loaned out to Columbia for an eight-day quickie called

The Menace

("I fainted a lot, as bodies fell out of closets"), and to Capital Films where she played a bootlegger's girlfriend, opposite Pat O'Brien. The reviews for both films were tepid, and in the last month of her Universal contract she was dropped. Disconsolate, Davis and her mother were packing to return to New York when the phone rang and she was asked to test for a picture with George Arliss at Warner Bros. studio in Burbank: She got the role and a six-year contract, which she happily signed.

That first year at Warner Bros., Bette made six films, playing "ingenues and sweet silly vapid girls." During this time she was named 'A Star of Tomorrow" by a group of theater exhibitors. The presentation of the award would also provide her first encounter, albeit removed, with a star of the day, Joan Crawford. The story of the evening was reenacted by actress Joan Blondell. "There was a bunch of us at Warner's who were chosen," said Blondell. "Ginger Rogers had just made

Forty-second Street,

and Bette and I were cranking out pictures by the hour, it seemed. Anyway, we were voted 'Most Promising Newcomers,' which meant we got to go to this banquet and have our pictures taken. It was considered good publicity, so we got all dolled up and they put a car at our disposal. The dinner was held at the Ambassador Hotel, where each one of us was supposed to get up and make a short speech over live radio, which was also a big deal. I remember Ginger had already spoken when it was Bette's turn to go up and accept her award. She was just about to speak when we heard these loud screams from the corridor outside the main room. The doors flew open and this absolutely gorgeous young couple entered the room. It was Joan Crawford and Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. The guys from the press and the radio crew fell over each other trying to get to the divine Joan and her equally divine husband. Bette never got to speak, nor did I. Actually, I thought it was quite funny, but not Bette. Years later she and I were seated together at a dinner for Jack Warner. Rehashing the old days, I said to her, 'Bette, remember the night when Joan Crawford stole the spotlight from us starlets?' And she froze. She acted as if she didn't know what I was talking about. I reminded her of the night at the Ambassador Hotel, until she stopped me.

'Joan!'

she said. 'You

must

be hallucinating. That

never

happened!' "

Crawford Takes on the Divine Garbo

Of course, Joan Crawford did not recall the incident either, or the exact moment in history when she had first heard of "Little Bette Davis." During the early 1930s Joan had more important things on her menu—namely, the dogged, slavish pursuit of her own career, and the careful refinement of her ever-changing public image. As Mrs. Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., and as an accepted, albeit delayed, member of the Pickfair royal court, Joan was happy at first with her new, respectable role in Hollywood society until she encountered a British journalist at Pickfair who described her to his English readers as "the Pickfords' plump young daughter-in-law, with huge hungry eyes, and a rather homely manner." Reading that notice, Joan decided some immediate physical changes were in order.

She lost more weight ("I haven't tasted sugar or starch in six months, and I never touch alcohol," she boasted to another Pickfair guest, George Bernard Shaw, who was not quite sure of just who she was). After altering the shape of her face by having her back teeth removed to give her cheekbones, she had her front teeth, which were spaced and filled with dental cement during her early days of filming, filed down to allow temporary caps to fit over them. The painful procedure, however, infected her gums, which stretched her mouth. When the swelling subsided, it left her with a larger upper lip. Pleased with the extension, she decided to paint in her lower lip, giving the world "the Crawford mouth," which in years to come, not unlike Bette Davis, she would extend and exaggerate as her whim dictated.

The corresponding Crawford hallmark, the imposing wide shoulders, would come courtesy of Adrian, the noted M-G-M couturier. "My God," said the designer when the semiclad, wideshouldered Joan stood before him, "you're a Johnny Weissmuller." Viewing her size-forty-nine shoulders, the designer quipped, "Well, we can't cut them off, so we'll make them wider." And so the famous Joan Crawford shoulder pads were born. (Years later Adrian would confess that the padded shoulders also helped to distract attention from another Crawford liability, her big hips. "To offset her womanly hips, I developed the idea of broad shoulders," the designer told

Womens Wear Daily.)

Crawford was always the first to admit that her screen persona was in a constant state of flux in the early thirties. "I experimented with different styles," she said. "When one look didn't work, I dropped it and moved on to another." Portrait photographer Cecil Beaton met up with the actress during one of her transitional phases. "She has become one of the most exotic pieces of affectation on the screen," said the self-invented society lens-man. "It is occasionally most enjoyable to watch her exaggerated Frattellini clown makeup of white face, goggle eyes and enormous persimmon lips." Noting that behind the mask "a detective is needed to discern any expression other than surprise," Beaton regarded the star as "ordinary ... childish and uncertain," and wondered when she would get over her schoolgirl crushes on other female movie stars. 'At one time she was insatiably interested in Miss Dietrich; then the Fairbanks Jr. house was littered with Marlene's photographs and gramophone records. Then she moved on to Lilyan Tashman, followed by the chief of her idols—Greta Garbo."

In 1932 Crawford, and most stars in Hollywood, had to stand in line to worship at the shrine of the sublime Miss Garbo. When Joan first saw the Swedish actress on the Metro lot she confessed, "My knees went weak. She was breathtaking. If ever I thought of becoming a lesbian, that was it."

Bette Davis was also quite taken with Greta. "Oh, Garbo was

divine,"

she said.

"Sooooo

beautiful. I worshipped her. When I became a star, I used to have my chauffeur follow her in my car. I always wanted to meet her."

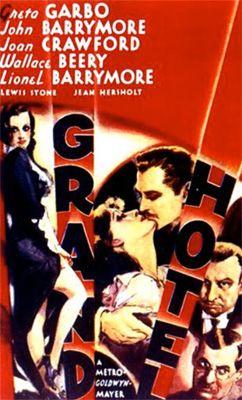

Bette never got to meet Greta, but Crawford did. It was Garbo, in fact, who provided Joan with her first class-A talkie,

Grand Hotel,

and, in typical competitive ex-showgirl fashion, Joan would attempt to steal the picture from under the inscrutable one's nose.

The synopsis of the German play came to the attention of M-G-M producer Irving Thalberg in 1930. It focused on a group of people, of diverse backgrounds, whose paths crossed in a plush hotel in Berlin over a forty-eight-hour period. One of the leads, the role of an aging prima ballerina who is losing her grip on her art and her life, seemed perfect for Greta Garbo. Thalberg arranged to invest fifteen thousand dollars in the forthcoming Broadway production. When the play, followed by a novel, became a huge popular success, M-G-M made an unprecedented move. They announced they were assembling an all-star cast for their seven-hundred-thousand-dollar movie. The primary cast would be Greta Garbo, John Gilbert, Joan Crawford, Clark Gable, and Buster Keaton as Kringelain, the doomed bookkeeper, at the hotel for one last fling before his demise.

The first to dropout of the ensemble was Greta Garbo. "I t'ank I go home [to Sweden]," she said, a threat she was fond of using whenever scripts, money, or leading men did not meet her aesthetic approval. In this instance it was the choice of John Gilbert as her leading man that upset Greta. The two were lovers, but had recently quarreled, and it was up to Thalberg to tell Gilbert he was out of the picture (wherein the spurned matinee idol went on a prolonged bender. . . and fired several pistol shots at a pair of lovers parked on his property line). Robert Montgomery was then tested for the part of the baron who steals the ballerina's heart and jewels. He looked too young, and the role went to John Barrymore. Clark Gable as Preysing, the corrupt industrialist, was also considered too young and was replaced by Wallace Beery, with Lionel Barrymore taking over for Buster Keaton (whose consumption of alcohol had made him "undisciplined," said L. B. Mayer).

A month before

Grand Hotel

was scheduled to begin production, an article in

Screenland

magazine questioned the choice of Joan Crawford for the role of the slut-stenographer, Flaemmchen. "Having donned the manner, voice and personality of a great young lady in her private life," said the magazine, it remains to be seen whether she can unbend sufficiently to become the shabby, tragic little Berlin secretary." A few days later Joan attempted to withdraw from the cast. Garbo had all the glamour and the love scenes, while she had to shlep through the entire picture wearing one dress. Thalberg told her she was a fool to pass up the role of the money-hungry stenographer.

"You said you wanted to be an actress in prestige pictures," he told her.

"Yes," said Joan, "but why must I look so shabby, with only one dress?"

"Adrian will make you

two

dresses, and a peignoir," Thalberg promised.

"Okey-doke," said Joan.

On December 30, 1931, rehearsals for

Grand Hotel

commenced on soundstage five at M-G-M. A long table and chairs had been set out for the principals, and the first to arrive was Miss Crawford. She swept onto the soundstage with her dog, Woggles, and seemed upset when she learned she had preceded the other stars. "Her habit of punctuality cheated her of a good entrance," said director Edmund Goulding. When John and Lionel Barrymore entered, followed by Wallace Beery and Lewis Stone, Goulding distributed the updated revised scripts and called the cast to order. They would read the script straight through, he said. "But Miss Garbo has not arrived," said Joan. "Miss Garbo has been excused from all rehearsals," Goulding announced.

Joan was crushed. She had mentally rehearsed a little routine for this, her introductory meeting with her idol. Her disappointment turned to anger when she learned that she had no scenes in the film with the great Garbo and that, furthermore, all of the leading star's major scenes would be shot on a separate soundstage, on a set closed to visitors. There would be no intimate chats for Joan, no posing together for publicity stills. As she would intone three times throughout the picture, the elusive Swede "vanted to be left alone."

On January 14, 1932, Los Angeles newspapers covered two unusual events. Snow fell in Hollywood, and "John Barrymore met Greta Garbo for the first time on the set of

Grand Hotel."

Barrymore had arrived early, before Garbo, who positioned herself by the main gate and waited to pay Barrymore the honor of escorting him to the set. 'A half an hour went by before the situation was straightened out," said a reporter. After their opening scene, the usually reserved Garbo impulsively kissed her costar. "You have no idea what it means to me, to play opposite so perfect an actor," she said. Introduced to a Barrymore friend, Arthur Brisbane, Garbo was shocked to learn that the man was a member of the working press, the editor of the New York

Journal.

"But I used to work for him," said Barrymore. "You? A member of the press?" said the horrified Greta. "I was a cartoonist," he explained. ''Aaaah,'' she sighed with relief. "That's better. Much better."

During the last week in January, the opening and closing hotel lobby scenes of the film were shot on soundstage six. All of the principals and sixty-five extras were on call to make their entrances and exits through the gigantic Art Deco foyer designed by Cedric Gibbons. To avoid contact with her costars, Garbo's scenes were scheduled after lunch, so on the morning of the shoot Crawford called in sick and had her scenes rescheduled for the afternoon. As the director rehearsed the extras, whose shoes had been soled with cork to prevent noise on the marble floors, Garbo sat apart in the spacious lobby, dressed in chinchillas, perched on a little box, eating an apple, her eyes half closed. "She cut the apple into little pieces with a knife," said a reporter. "She would have bitten into it only it would have spoiled her make-up." Her black maid, Ellen, called "L-I-I-I-n" by the star, stood nearby, with a napkin and a brown paper bag in her hand, in which the core of the apple would be disposed of when her mistress was through. "The walls behind the Garbo began to move," said the writer. "She turned, startled like a deer in the forest. She noticed the walls had wheels. It pulled away. 'What ees thees?' Garbo cried. Suddenly from the other side of the walls came the sound of Bing Crosby's voice, singing 'Can we talk it over, dear?' Garbo jumped, looked around her. 'What ees thees?' she asked again. 'Miss Crawford's dressing room,' she was told."

"Nice," she said.

The door of the palace opened. Joan Crawford put her head out and called to the man who did nothing but change the Bing Crosby records on the phonograph set up for her in the sidelines. "Put the other piece on, dear," said Joan, preparing for her appearance in the lobby.

"What other piece, Joanie?" the man answered.

"You know, Ed," she said.

"What's the scene, Joanie?"

"Oh, kind of gay and bright."

Garbo, back on her box, looked from one to the other as their voices crossed, then called to her maid.

"What ees the scene, L-I-I-I-n?"

"You walk through the people in the lobby," her maid answered.

"Then it ees very sad," answered Garbo.

The director seated on the crane above the lobby asked for quiet, and instructed Garbo that she was to walk from left to right and exit through the revolving doors.

"I valk on my own?" the actress asked.

"Through a crowd of admirers," the director said. "Do you wish to rehearse?"