BELGRADE (18 page)

Authors: David Norris

Serbia had very little industry, hardly any banking facilities, poor infrastructure in roads and communication links, and worst of all it had little prospect of being able to improve its position in the short term. Literacy rates in the villages were as low as 23 per cent, but higher in the towns at about 55 per cent. Most Serbian towns numbered between 5,000 and 10,000 inhabitants, with a few larger ones: Vranje (pop. 10,600), Šabac (12,000), Požarevac (12,500), Leskovac (13,500), Kragujevac (14,500), Niš (25,000) and Belgrade.

The capital city’s population grew from 70,000 in 1900 to 90,000 by 1910, although, in comparison to neighbouring countries, it was fairly small alongside Bucharest’s 287,000 inhabitants and Athens with 122,000. The occupations of Belgrade’s inhabitants reflected its position at the centre of political, economic and administrative life: civil servants (24 per cent), artisans (23 per cent), professional groups (21 per cent) and merchants (13 per cent). The architectural space they created attests to their cosmopolitan taste and their promotion of cultural and social activity.

After the death of King Alexander, new opportunities opened up for public debate. An independent newspaper,

Politika

, began publication in 1904, founded by Vladislav Ribnikar (1871–1914), which today still has the largest circulation in Serbia and has become the longest-running daily paper in the Balkans. Coming as a breath of fresh air, it appeared as a sign of change in Belgrade’s cultural, intellectual and political life. The city’s elite, educated in the best European universities, was aware of the immediate need for a constitution defining the rights and responsibilities of the crown, ministers, the National Assembly and courts of justice. This circle of leading citizens was able to discuss the relative merits of the British and French political systems, and to debate the principles of freedom and justice to be applied via the institutions of government. However, the political culture in which these polemics were conducted at the beginning of the twentieth century remained highly specific to Belgrade, quite unlike the context of London and Paris from which the models were taken.

An important factor in the city’s social structure was the small number of people in these upper echelons and the consequent trend for individuals to appear across a broad range of functions. It was not unusual for professors from the University of Belgrade to sit alongside professional politicians as deputies in the Assembly drafting legislation. Such people were very much aware that they needed to play an active role in order to provide a lead for the country. But where in the West there was a greater tendency toward the atomization and professionalization of institutional processes, in Belgrade there emerged a single elite group to perform the different functions normally divided among different sub-groups. This personal touch tended to distort the emergence of political parties in Serbia, giving public debates the appearance of family feuds.

Belgrade was not a natural capital city for Serbia. The medieval centre of the state was further south, while Knez Miloš, wary of the pasha, made Kragujevac his capital. Belgrade was perched above the meeting-point of the two rivers in the north-west corner of the country, its geographic position symbolic of its western leanings. Its architectural appearance from Miloš’s time and later was influenced by the West, as were its models of government. But Serbia was a fragile entity, in constant danger of losing its independence and its identity. These fears were heightened in the decade before the First World War as the Austro-Hungarian Empire began to realize its plans to extend its territory in the region. It formally annexed Bosnia in 1908, having held administrative control since the Berlin Congress of 1878. From 1906 to 1911 Vienna closed its borders and refused to allow Serbia to export goods across its territory to the West.

These developments no doubt influenced the Belgrade elite’s thinking about political priorities. The first step was national liberation, while the rights and freedom of the individual would follow once the safety of the collective was assured. The historian Dubravka Stojanović recognizes the weight of traditional patriarchal values in her judgment on Belgrade’s political culture. She observes that the elite were happiest when discussing the principles of democracy that they studied and experienced in the West but that they “added to these ideas local colours, translating them from the abstract utopias to the older, better-known models, much closer to the Serbian tradition”. The times, however, were difficult; and time did not appear to be on Belgrade’s side.

HE

F

IRST

W

ORLD

W

AR AND THE

C

REATION OF

YUGOSLAVIA

In 1914 the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand visited Sarajevo, the principal town of the newly-acquired province of Bosnia. His stay happened to coincide with the anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo. A small band of conspirators planned his assassination, led by Gavrilo Princip who at seventeen was one of the oldest among them. They were helped by a secret society in Belgrade called “Unification or Death”, or sometimes the “Black Hand”, which provided arms and money. One of the leading figures in the society was the same Colonel Dragutin Dimitrijević–Apis who had been active in the plot against Alexander in 1903. Both Princip and the colonel met their ends in 1917; Princip died in jail and Apis was put on trial before a military tribunal engineered by his many enemies and shot for treason in Greece. After the death of the archduke and his wife in Sarajevo, Vienna demanded that Serbia take responsibility for the assassination. The Austrian demands, however, were formulated in such a way that Belgrade was bound to reject them, since acceptance would require Serbia to surrender its sovereignty.

The first shell of the war was aimed at Belgrade on 29 July 1914. Much to everyone’s surprise, the first Austrian invasion was repulsed, but after a renewed attack the country was occupied by enemy forces the following year. The city suffered greatly in the bombardment of 1915 with great loss of life and much damage to its infrastructure. The Austrian authorities, once in control, were determined to eradicate as far as possible all outward forms of Serbian identity. The Cyrillic alphabet was banned from public use, printing presses were smashed, street signs and destination boards on trams were changed into the Latin alphabet, and history books in schools were rewritten to downplay national achievements.

Belgrade became a cultural desert with most of its pre-war intelligentsia retreating with the army and taking refuge on Corfu from where the government-in–exile continued its work. The poor health of King Peter forced his retirement from an active role and his son, Alexander, was made prince-regent. After the Allied victory in 1918, Serbia was joined by Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Montenegro and Vojvodina in an enlarged state of South Slavs. The creation of this first Yugoslavia, known officially as the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, was announced by Prince Alexander in Belgrade on 1 December 1918.

In the immediate post-war period, Belgrade suffered all the problems common to other urban societies in the aftermath of large-scale conflict. The old town families suddenly found themselves surrounded by thousands of newcomers. Some of them were poor, dispossessed refugees, while others lived by their wits taking advantage of the anarchic conditions into which Belgrade was plunged at the end of the war. It was the capital of a country without internationally recognized borders, not even a name. The author Ivo Andrić describes the atmosphere in the city in his novel

Gospođica

(1945), translated into English under the title

The Woman from Sarajevo

:

Life in Belgrade in the year 1920 was gaudy, lusty, unusually complex, and full of contrasts. Countless diverse vital forces flowed parallel with obscure weaknesses and failings; old methods of work and the strict discipline of patriarchal life existed side by side with a motley jigsaw of new and still unformed habits and chaos of all kinds; apathy side by side with intensity, modesty and every kind of moral beauty with vices and ugliness. The panting and reckless bustle of various profiteers and speculators took place alongside games of intelligence and the dreaming of visionaries and bold ideologists.

Down the worn and partially destroyed streets came this foaming and swelling flood of people, for each day hundreds of newcomers dived into it head first, like pearl fishers into the deep sea. Here came the man who wanted to achieve distinction and the man bent on hiding himself. Here mingled those who had to defend their possessions and their status, threatened by the changing conditions. Here were many young people from all parts of a state that was still in the process of formation, who looked forward to the next day and expected great things of the changed circumstances, and also a number of older people who looked for a means of adjustment and for salvation in this very flood, hiding the fears and the loathing which it inspired in them. There were many of those whom war had thrown up to the surface and made successful, as well as those it had rocked to their foundations and changed, who now groped for some balance and for something to lean on.

The new country was greeted enthusiastically by almost all, although initial euphoria was soon replaced by disappointment. Croats especially had been hoping for a greater degree of autonomy than the government in Belgrade was prepared to allow. Following their political traditions, Belgrade’s politicians assumed that the new state would be a parliamentary monarchy with centralized institutions in the capital city. Unfortunately, neither the Karađorđević dynasty nor Belgrade held the same emotional resonance for all the population. The Croat deputies were mostly elected from the ranks of the Croat Peasant Party under the leadership of Stjepan Radić. Denied their home rule, the Croats initially boycotted the National Assembly, but eventually agreed to take up their seats. Shortly afterwards, however, in the summer of 1928 Radić was shot and killed during a debate in the Assembly by a Montenegrin deputy, Puniša Račić. All possibility of compromise was now gone and the ordinary operation of government proved impossible. Faced with an extreme situation, King Alexander dissolved parliament and took power in his own hands on 6 January 1929. In the same year, he renamed the country the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in preference to the title that had emphasized the presence of three different and by then reluctant partners.

Opinion is divided over Alexander’s actions. Was he genuine in his stated aim to reunite the country, or was he another Serbian public figure who could not understand the nature of the political problems facing the enlarged country? The question was never answered as he was assassinated during a state visit to France in 1934 after landing in Marseille. Both internal and external enemies were implicated in the plot, in particular the Croatian fascist movement the Ustaše, banned in Yugoslavia, which was in turn supported by Mussolini’s Italy. Alexander’s son, Peter, was still a schoolboy and too young to take the throne so the late king’s cousin, Prince Paul (or Knez Pavle), became regent. The prince never expected nor wanted to be a political figure. He was a connoisseur of art, an Anglophile whose brother-in–law was the Duke of Kent, and clearly was not prepared for the huge task ahead.

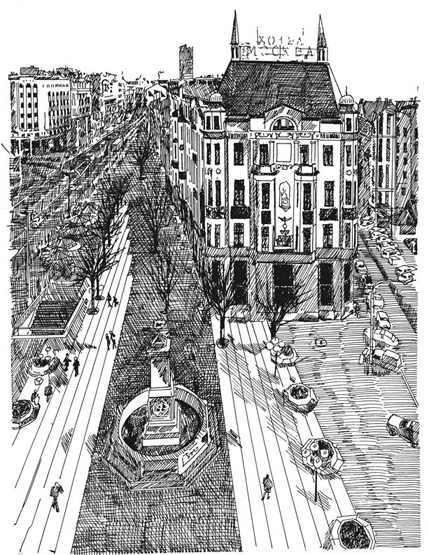

ERAZIJE

The street leading from the end of the pedestrian-only Knez Mihailo Street to the Slavija Square is a long straight road actually made up of two parts: Terazije and King Milan Street. In Ottoman times the main water supply to Belgrade flowed under here toward Kalemegdan. At certain intervals stood tall towers made of wooden boards marking little reservoirs for drawing water. These towers were called

terazije

in Turkish and one was placed in front of where the Hotel Moskva now stands—hence this street’s name.

In the 1830s this area just beyond the city perimeter was marshland with a reputation as a good spot for hunting wild ducks. The only sign of human activity was the road that curved up from the Istanbul Gate and divided here, one route leading down what is now King Alexander Boulevard for Smederevo and ultimately Istanbul, the other following King Milan Street and the road to Kragujevac and central Serbia. The land formed a small plateau with a view down to the River Sava and the first Serbian district of Belgrade around the Town Gate.

The first development on Terazije was at the initiative of Knez Miloš to expand beyond the confines of the Ottoman town. He had the idea of giving free parcels of land to Serbs living further down the slope on condition that they build homes and workshops on the plateau above. Priority was given to craftsmen like blacksmiths and wheelwrights since these trades would be useful on the highways for travellers, merchants and their caravans arriving or leaving with their goods. In time it became a busy stopping point with people plying their trade, repairing carts, fixing horseshoes and other businesses. It was also possible to link this new development directly with the Town Gate without going through Belgrade’s Turkish quarter.