BELGRADE (15 page)

Authors: David Norris

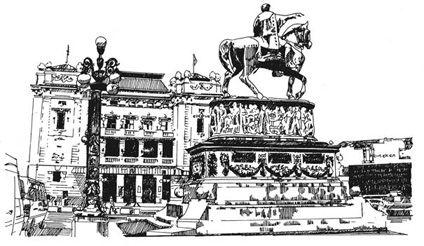

After the fall of communism, however, such events have not always been to the advantage of the ruling regime. A huge opposition rally converged on the square on 9 March 1991, forcing the government to impose a crackdown by bringing in water cannon to disperse the crowds. Large anti-Milošević demonstrations met here again during the popular daily protests between November 1996 and February 1997. During the NATO bombing campaign against Serbia in 1999 there were daily concerts by the country’s most popular artists, keeping up citizens’ morale during daylight hours before the sirens warned of air raids in the evening. In more peaceful times it is used to stage many events and performances for BELEF, the Belgrade Summer Festival in July and early August, and for a massive New Year’s Eve party.

TUDENT

S

QUARE

Student Square is at the end of Vasa Čarapić Street and is the terminus for public transport running past Republic Square. In Ottoman Belgrade this was the site of the main graveyard, with numerous mosques and other Muslim religious institutions in the vicinity. A trace of this graveyard is evident in the mausoleum on the corner of Višnjić and Brothers Jugović Streets, built in 1784 for the burial of Šejh-Mustafa Bagdađanin. From 1824 the Big Market (Velika pijaca) was moved here, linked by a straight road to the Istanbul Gate. By 1839 the market had grown so large that police had to regulate the positions of stalls and banned the sale of live pigs. It continued to function during the whole of the nineteenth century but was increasingly out of place. The market was a busy place for the sale of fresh fruit and vegetables, some of which would inevitably fall to the ground and rot. The unpleasant smells and dirtiness did not sit well with the elegant buildings going up in Knez Mihailo Street and the main square with the National Theatre. It also outlived its usefulness, as the new main residential areas were at some distance in Vračar and Palilula. In 1926 a convenient fire broke out destroying the market and providing the city government with the opportunity to transfer its business to the Green Wreath Market and to Kalenić Market (Kalenićeva pijaca) at the end of Crown Street in Vračar, both of which are still lively and operating today. With the disappearance of the Big Market, the area was planted as a park, with ornamental walls, gates and statues.

The Big Market was also known as the Market by the Main Police (Pijaca kod Glavne policije), as both the local Serbian and Turkish police were stationed along the lower road of the square, roughly on the corner with Višnjić Street. The Serbian gendarmes were moved a little way to the so-called Glavnjača during the 1850s. Their building no longer exists, having being pulled down to make way for the Faculty of Mathematics (Prirodno-matematički fakultet) in 1954. The Glavnjača was the main police headquarters with a prison in Belgrade where many suspects under different regimes were interrogated. It was used by the Obrenovićes, then taken over by the new authorities and before the Second World War often housed political prisoners; the Gestapo took it over during the war, then the communists for a brief period.

A number of important figures from the nineteenth century had their homes in or around Student Square. Alexander Karađorđević lodged for a time in a house where the Faculty of Philology now stands and where his son, Peter, was born in 1844. Gospodar Jevrem, the brother of Miloš Obrenović, and Toma Vučić Perišić were near neighbours here, while Ilija Garašanin, Knez Alexander Karađorđević’s foreign affairs minister, lived at the end of Uzun Mirko Street.

In keeping with the intention to create a city centre fitting for a European capital, the old buildings around the square were demolished and replaced by grander constructions. In 1863 Captain Miša’s House (Kapetan Mišino zdanje) was constructed and given to the city in a philanthropic gesture by a rich merchant, Captain Miša Anastasijević, to house many of Belgrade’s cultural institutions. Dositej Obradović’s Great School was moved here and joined by the forerunners of the National Museum and the National Library. In 1905 the school became the University of Belgrade, which continued to keep its premises in Captain Miša’s House. One of the tallest buildings in the centre, a cabin sat on its roof serving as a lookout point for fires in the city. It was damaged by Austrian guns in the First World War since an antenna was fixed on the roof as part of an experiment in wireless telegraphy. The main administrative offices of the University and some academic Departments are still here at 1 Student Square. The Faculty of Philology was built next door in 1922 and the Stock Exchange in 1934, which became the Ethnographic Musuem (Etnografski muzej) when the communists took power. The square has been renamed a few times. It was called the Great Square (Veliki trg) from 1872 to 1896, when it became the Royal Square (Kraljev trg) from 1896 to 1946, and finally Student Square.

ORĆOL

Dorćol extends down the slope from Student Square to the Danube although most places of interest are contained between the square and Tsar Dušan Street, and from France Street to Kalemegdan. In Ottoman Belgrade this was the main residential area for wealthier merchants and officials of the pasha’s administration. It was often referred to as either the Lower Town (Donja varoš) or the Turkish Town (Turska varoš) to reflect its geographic position spreading down the slope or its demographic structure. The part of town down the slope on the other side of the hill towards the Sava, for the same reason, was called the Serbian Town (Srpska varoš).

Dorćol resembled a typical oriental settlement of the Ottoman Empire. It appealed to foreign visitors, with gardens hidden behind high walls, winding streets and open-fronted shops with goods spilling outside. One Polish visitor, the writer Roman Zmorski (1822–67), described it as “a wonderful view of the East thrown within a hand’s reach of Europe”. During the Austrian occupation of 1717–39 Dorćol’s appearance changed considerably as the Muslim population moved out and some houses were demolished to be replaced by buildings in the baroque European style. The only house surviving from that period is at 10 Tsar Dušan Street, although it has gone through much refurbishment.

The Turks restored the oriental look of the area after 1740 when it again became an elite part of their town. The houses of the richest and most powerful Turks were then taken over by the leaders of the First Serbian Uprising. Karađorđe moved into the palatial premises formerly belonging to one of the Dahijas, Mula Jusuf, and his lieutenants chose similar accommodation for themselves. The area never really recovered its former glory after 1813 and Dorćol became rather neglected. The Jewish quarter was an exception to this general rule as it maintained its opulent appearance during the nineteenth century in the area below Kalemegdan around today’s Jewish Street.

The city’s Jewish community came to Belgrade at the end of the fifteenth century from Spain bringing with them their own language, Ladino. They were a solid community of merchants and artisans who comprised the third largest such enclave in the Balkans, after Istanbul and Thessalonica. There is plenty of evidence of good relations between the Serbian and Jewish communities in Belgrade; the first state printing press founded by Knez Miloš printed books both in Serbian and in Hebrew, while many Jews regarded themselves as Serbs of the faith of Moses. They were nearly all wiped out when the city was occupied by the Germans during the Second World War.

One or two examples of earlier architecture remain such as the mosque at 11 Gospodar Jevrem Street and the two museums on the same street, the Museum of Theatrical Arts (Muzej pozorišne umetnosti) at no. 19 and the Museum of Vuk and Dositej (Muzej Vuka i Dositeja) next door. The Museum of Theatrical Arts was built as the house of the Belgrade merchant family Božić in 1836. The Museum of Vuk and Dositej belonged to one of the secretaries for finance in the pasha’s administration before being taken over by Dositej Obradović during the First Serbian Uprising to house the Great School from 1808 to 1813. It has served other functions in its long existence, being used as the French Consulate for a time. It was restored after the Second World War when it was decided to make it into a memorial centre to celebrate the two most prominent representatives of Serbian letters.

There are other museums in the area: the Jewish Historical Museum (Jevrejski istorijski muzej) at 71 King Peter I Street and the Gallery of Frescos (Galerija fresaka) at 20 Tsar Uroš Street. The latter offers exhibitions of copies of medieval church art, painting and sculpture from Serbia. There is a monument on Gospodar Jevrem Street marking the spot where the young boy was wounded during a fight between Turkish soldiers and Serbian youths, eventually leading to the freedom of the city in 1867.

The liberation of Belgrade from the Turks that year gave an opportunity to a new generation of architects and planners trained in the West to put into action the proposals drawn up by Emilijan Josimović for the redevelopment of the centre of Belgrade. Dorćol was completely transformed. The old Ottoman quarter was pulled down and replaced by the present geometric shape; a set of streets runs down the slope toward the Danube with intersecting ones across in the direction of Kalemegdan. The Sava slope descends over the brow at the top of the hill. The central feature in this area is formed by the three connecting sweeps of the crescents called Obilić, Toplica and Kosančić. These three roads curve over the old trench that marked the city limits of Ottoman Belgrade. They are, appropriately enough given their position, named after three legendary heroes who fought the Turks (Miloš Obilić, Milan Toplica, Ivan Kosančić).

Opinions vary regarding these changes to the city centre. Some see the result as too planned to the extent that it seems artificial. Angles, widths and heights are too carefully measured and inhibit any sense of organic growth. Others differ and point to the elegance that these proportions lend to the overall effect of the central district. And, they argue, construction has continued to add new textures and contours to the urban skyline. No doubt, the debates will continue and constantly expand the dialogue between the urban setting and the people who inhabit it.

KADARLIJA

Skadar Street, known to all as Skadarlija, has long been famous for its kafanas, nightlife and bohemian atmosphere. It is positioned just outside the old town, parallel to France Street. In the early nineteenth century it was a Romany district with a reputation for hard drinking, where both Serbian and Turkish young men would come beyond the reach of their parents and “civilization”. Houses were poor and flimsy, looking rather like a shanty town. From the middle of the century more solid houses were built following traditional Balkan designs, the street was cobbled and in 1872 received its official title as Skadar Street. A large number of kafanas remained but the street’s reputation was transformed from a den of iniquity to a place for a respectable evening out. It particularly attracted customers from the arts, actors, writers and painters.

About 1890 Skadar Street boasted the greatest concentration of restaurants and drinking houses in Belgrade, some of which remain today: the Golden Jug (Zlatni bokal), the Three Hats (Tri šešira) and the Two Stags (Dva jelena). At no. 34 is the house of Đura Jakšić (1832–78), a poet and painter who had a reputation for falling out with the authorities. Many of his paintings hang in the National Museum and his house is often used as an exhibition centre or for literary evenings where writers read from or discuss their work. His poetry, and the work of others such as Jovan Jovanović–Zmaj (1833–1904) and Vojislav Ilić (1860–94), was typical of later Serbian Romanticism. Zmaj is also well known as a poet for children. His verses are still read to them, and it is not unusual for adults remembering their earliest contacts with literature to be able to quote at length from his work.

The Three Hats is about half-way down on the corner with Gospodar Jevrem Street. Opened in 1864, it took over from the Dardanelles when that establishment was pulled down and its artist customers needed a new local. Branislav Nušić (1864–1938), a writer of plays and short stories, also penned many witty and satirical articles, one of his favourite subjects being the city’s kafanas. Writing about one in Skadar Street, he noted:

The Three Hats is today the most popular kafana in Skadarlija. It has been in its time the seat of Belgrade’s bohemians, but another kind of public has joined them... It used to be the house of the father of Đoka Dimović who ran the Imperial. The father was a milliner repairing and applying dye to old hats. His house, in which he lived and worked, had a sign on which were painted three hats, each of a different style. The kafana has taken its name from that sign.

His article offers a fascinating introduction to this Belgrade social institution. The term comes from a combination of two Turkish words,

kafa

and

han

, a place for drinking coffee. The Serbs introduced alcohol but there is no evidence that the move was resisted by the Turkish inhabitants of the city. Most also serve food, tending towards traditional Serbian dishes rather than international cooking. Nušić analyzes the names of kafanas. The early ones were simply named after their owner, then later by reference to their location or to historical events or figures. The latest craze in the city centre in Nušić’s time was to adopt foreign names such as Union, Splendid, Excelsior and Palace—a trend of which he disapproved as they often replaced older names. He writes scathingly of one called the New Age (Novi vek) which had undergone what he clearly regarded as needless “modern refurbishment”, with—of all things—a jazz band and dancing. Obviously for him a kafana was not intended for such frivolous amusements, but a place for drinking, cards and conversation.