BELGRADE (7 page)

Authors: David Norris

The Victor is clearly visible from the monument to the communist era, just a short walk through the King’s Gate (Kralj kapija). There was a gate here from medieval times but the Austrians replaced it in 1725 with a much stronger defensive fortification incorporating a drawbridge. The gate leads to a series of steps, past the Roman Well (Rimski bunar) and up to the main plateau of Kalemegdan. The Roman Well is a complete misnomer as it has nothing to do with anything so far in the past, being sunk by the Austrians in the period 1721–31. The well’s shaft is almost 200 feet deep, taking it over thirty feet below the surface of the Sava, since its purpose was to provide the fort’s defenders with a plentiful and safe supply of drinking water during a siege. The wall of Kalemegdan stretching away from the Victor is where people sit and take in the view, giving justification to another name by which the Ottomans knew this place:

fećir bajir

, or the hill for contemplation.

The plateau behind, a grassy area crisscrossed by paths with benches and trees, has been the focal point of all the forts built here. This was the Upper Town (Gornji grad), the nerve centre for military and government life in Belgrade and the surrounding region. Stefan Lazarević built his palace on this mound, the Turks had a mosque with quarters for the janissaries, and Austrian soldiers were housed in barracks. It gave the ruling power an inner sanctum, a last redoubt in case of siege. It was securely positioned on top of the hill, while the walls, towers and earthworks tucked behind the Sava and Danube provided the first lines of defence. A small gate built into the white walls of the Upper Town not far along from the Victor is another Austrian improvement from the eighteenth century made on an older structure. It is called Defterdarova kapija, marked by a water fountain at its side erected in 1577 in honour of Mehmed Pasha Sokolović, and from here a path leads down to Kalemegdan’s Lower Town (Donji grad). The Lower Town toward the river used to be an integral part of the city’s defences and also the site for the quay at which ships would dock to load and unload goods and supplies.

The ruins of a building which it is thought once belonged to the seat of a bishopric are at the bottom of the slope in the Lower Town. Archaeologists found an inscription here relating to the time of Despot Stefan Lazarević. Close to these ruins is a white, oriental structure that used to be one of the seven public Turkish bath-houses, or

amam

, in Belgrade built at the beginning of the nineteenth century, and the only one remaining from Ottoman times. Rebuilt in the first half of the 1960s, it was then used as an observatory. Toward the river from the bath-house is a line of buildings. First is an Austrian gate from 1736 named after the Emperor Charles VI (Kapija Karla VI). Its luxuriously Baroque style serves as a fitting symbol of the extensive modifications and building programme initiated by the Habsburgs. The building next door, from the end of the eighteenth century, has been both a workshop for the production and repair of cannon and an army kitchen. It is now used as a base by the archaeologists who dig and research the area.

The medieval tower that completes this string of buildings, the Nebojša Tower (Kula Nebojša), is from 1460. It was originally intended as a defensive feature but the Turks converted it into a prison in the eighteenth century with a dark reputation as a place from which inmates rarely returned. Another monument stands near Nebojša Tower, by the river, recalling the bravery of the soldiers who defended Belgrade from Austrian assault in 1915. Heavily outnumbered, the Serbian commander, Major Dragutin Gavrilović, ordered his men to defend their position at all costs. His words are etched on the memorial. Addressing them as soldiers and heroes, he went on to say: “The High Command has struck our regiment from its register of active service. Our regiment is sacrificed for the honour of the Fatherland and Belgrade. You do not have to worry for your lives, which exist no longer... So forward, to glory!”

Military functions are long gone and the Lower Town, like the Upper Town, is now a place for recreation where visitors can stroll around what remains of the gates and walls of the old fortress. Members of the sports club Dušan Silni played the first football match in Belgrade close to Nebojša Tower in May 1896. In the 1930s it was suggested that the city build an Olympic stadium on this large, flat and empty space, but opponents objected that the site was far more important for its historical significance and that it should be left alone. Since then other facilities have been added including moorings for small boats, floating restaurants, a large sports centre, a pedestrian path and a cycle route. In recent years rugby matches have been played here and, it has been rumoured, staff from some of the embassies in town have come out to play cricket. It also now provides the site for the Belgrade Beer Festival held every August. Much of the Upper Town, too, is also given over to sports and other events, with courts for basketball, tennis and five-a-side football, venues for concerts beneath the fortress walls, and space for outdoor theatre performances during BELEF (Belgrade Summer Festival) held annually in July and early August.

The end of this section of Kalemegdan’s wall is marked by a stout tower, Dizdareva kula, and two gates, Despotova kapija and Zindan kapija, all from the fifteenth century, while beyond these structures the Austrians built Leopold’s Gate (Leopoldova kapija). Another path between Despotova and Zindan kapija also leads down to the Lower Town. On the way it passes by a small church dedicated to the Most Holy Mother of God, but popularly known as the Rose Church (Crkva Ružica). Originally a gunpowder store, it became the garrison chapel after Kalemegdan was handed over by the last Ottoman pasha to the Serbian authorities in 1867. It was ruined during the bombardment of Belgrade in the First World War and rebuilt in the 1920s.

The two statues on either side of the door represent military figures, one a medieval knight and the other a soldier from the First World War. Inside the church is a painting of the Prayer in Gethsemane on which the faces of contemporary figures are to be found: the Serbian king and his son, Peter and Alexander Karađorđević; the Russian Tsar Nicholas II; and the Serbian politician, Nikola Pašić. Two bells inside the church were cast from captured Turkish cannon as were two icons in relief of the Virgin Mary and St. George. Another church, this one to St. Petka, stands just a little further down the slope. It was built in 1937 above a spring from which, it is said, curative waters flow. When digging the foundations of the church, workmen found many skeletons of soldiers who fell defending Belgrade during the First World War which were removed and interred in a special vault close by.

Kalemegdan Zoo is close to Leopold’s Gate. It is quite unremarkable except for a monument in its centre to its most famous simian inhabitant. Sami, or Sammy, was a chimpanzee who came to live here in January 1988 until his death in September 1992 and who managed to escape twice. The first time he was soon caught and brought back. He became an urban legend, however, when he broke out for the second time. He was chased into the courtyard at 33 Tsar Dušan Street where he climbed into a cherry tree and then onto a garage. News of his escape spread quickly and over four thousand people turned up to lend him their support. Newspaper reports tell of people holding placards with slogan such as “Sammy, we’re with you!” and “Don’t give yourself up Sammy!” Eventually he was shot with a drugged dart and recaptured but not before he had become one of Belgrade’s foremost heroes.

Besides the zoo, Kalemegdan houses the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments of Belgrade (Zavod za zaštitu spomenika kulture Beograda) situated behind the Victor, the gallery of the Natural History Museum (Galerija prirodnjačkog muzeja) and the Military Museum (Vojni muzej), both near Karađorđe’s Gate (Karađorđeva kapija). Up from the zoo and towards the entrance to the park from Knez Mihailo Street stands a grand pavilion named after Cvijeta Zuzorić (1555–1600), a famous Dubrovnik poetess of the Renaissance period. It was built in 1928 and was the first dedicated exhibition space in Belgrade, becoming the centre of artistic life until the Second World War and adding enormously to the city’s image as a modern European capital with an active cultural scene. Today it is by no means the only such space but it still hosts regular exhibitions in the spring and autumn, as well as individual and group showings of foreign and Serbian artists.

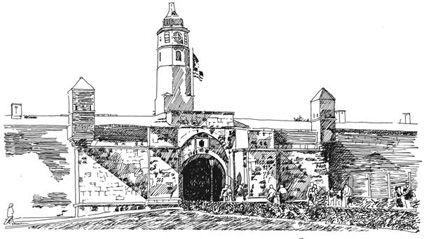

Back at the entrance to the park, the main path leads to an impressive statue of a female figure, the Monument of Gratitude to France (Spomenik zahvalnosti Francuskoj), erected in 1930 as a symbol of Serbia’s recognition of French help in the First World War. Serbia felt culturally close to France, more so than to the Anglo-Saxon countries. Many Belgrade scholars attended French universities in the early twentieth century, and writers and artists would visit and take inspiration from the latest stylistic developments, while French fashions set the tone for Belgrade’s high society. Two compositions in relief on the base of the pediment express these feelings. The suffering of Serb and French soldiers is depicted on one side, and a woman with children representing the help given by France to Serbian refugees is on the other side. Behind the statue a path leads in rapid succession through two gates built as part of the Austrian defences in the eighteenth century. The first is Karađorđe’s Gate and the second is the Inner Istanbul Gate (Unutrašnja Stambol kapija). The Clock Tower (Sahat kula) stands further on and it houses a small exhibition of Kalemegdan’s development over the centuries.

The writer Sveta Lukić in his 1995 book of memoirs has a description of Belgrade in constant turmoil, but guarded by the fortress of Kalemegdan looking like an armour-plated boat when spied from the confluence below:

... its deck is the Upper Town, the Rose Church and Clock Tower are like chimneys, on the bridge stands the Victor, Meštrović’s sculpture turned toward his Yugoslav brothers over the Sava. The boat sails on unfalteringly, as if bewitched. There is no other course than across the Pannonian Sea to Europe.

The central plateau of the Upper Town is gained once more on the other side of the Clock Tower where a six-sided Turkish mausoleum or

turbe

made of stone stands on the grass in a fairly central position. Ottoman Belgrade contained about ten of these ornamental graves of which only two remain—this one and another on Student Square. This

turbe

is the burial chamber of Damid Ali Pasha, a successful soldier against the Austrians in the eighteenth century. Two other prominent Turks, Selim Pasha and Hasan Pasha Češmelija, were interred alongside him in the midnineteenth century. The

turbe

inspired the author Ivo Andrić to write his short story “The Excursion” (Ekskurzija).

HE

E

XCURSION

Andrić (1892–1975) is the best-known writer to have lived in Belgrade during the twentieth century. His place as a writer of world renown was affirmed with the award of the Nobel Prize for literature in 1961. His novels and many of his short stories have been translated into English, but not this one. There are very few works of Serbian literature in which Kalemegdan is a major setting. The whole fortress, Upper Town and Lower Town, was closed to the Serbs during the many centuries when it was a centre of colonial power for Turks and Austrians. It was handed over to the Serbs when the Ottoman Empire quit the city in 1867 and although much of it was designated as a public area from the 1870s it continued to be used as a military base until finally demilitarized in 1946, when the last soldiers, including a contingent of Soviet troops, left their barracks. Then, it was truly opened up for all to enjoy.

The park is mentioned in literature from the beginning of the twentieth century as a place where lovers would take a stroll, but Andrić’s short story, first published in 1955, marks the first time it receives more than a passing reference. The story gives a vivid impression of the atmosphere of the park and has a ghostly feel with its reference to Damid Ali Pasha’s burial chamber.