BELGRADE (20 page)

Authors: David Norris

King Milan Street was refurbished after the First World War and many new buildings were planned for it, all finished in a few short years. The consequent transformation produced a central avenue in the style of other European capitals fronted by tall buildings of impressive design and dimensions. The House of the Serbo-American Bank (Dom Srpskoamerikanske banke) went up in 1931 at no. 10. The Hotel London was built on the corner with Knez Miloš Street, and the name of the crossroads is still known to all as “At the London” (Kod Londona). Construction after the Second World War has produced many more newer buildings that may individually have their merits, but which rarely blend with the earlier architecture. The street has hence lost something of its coherency.

Across the road from the palace complex is the Serbian Assembly, built 1953–54 in a modern design unlike the classical proportions of the buildings opposite. In 1963 the Chamber of Commerce (Privredna komora Beograda) was constructed on the site of the old Hotel London with little thought to the appearance of surrounding buildings. From 1969 to 1974 the city’s tallest skyscraper was constructed on the street, the Belgrade Palace (Beogradska palata)—more frequently and affectionately called the Belgrade Lady (Beograđanka). It can be seen from all over the city and defines the central skyline and, although impressive in its own way, hardly blends with the surrounding architecture. It is spread over 23 storeys with a supermarket in the basement, a department store on the first few floors, office space on the upper floors and the studios of a TV and radio company on the very top floors.

The area around the Beograđanka was first developed by Knez Miloš as part of a military district including barracks and a powder magazine. Across the road, the Student Cultural Centre (Studentski kulturni centar) was originally built as the Officers’ Club (Oficirski dom) in 1895, part of the facilities for the army. The small statues of knights on the front betray its earlier incarnation, and it was from here that the conspirators set out on their errand to murder King Alexander and Queen Draga in 1903. Behind the cultural centre is a park bearing the name Manjež, from the French word

manège

, meaning both the art of horsemanship and a place for training horses. This was the site of a riding academy that Knez Mihailo added to the military complex in the 1860s as a training ground for the cavalry of the Serbian army which he was keen to develop. The need for the facilities declined after the First World War for two reasons. First, the war saw the introduction of certain technological advances which, while not doing away with the use of cavalry altogether, at least reduced their military effectiveness. Second, the National Theatre in the centre of town was damaged during the war and was not fit for staging performances. In these circumstances, it was decided that the adaptation of the Manjež, the large hall intended for cavalry drills, as a new theatre would solve one of the city’s temporary problems. This building fronted the park on King Milan Street and eventually became the home of the Yugoslav Drama Theatre (Jugoslovensko dramsko pozorište). Its most recent facelift came about following a catastrophic fire in 1997 when the whole building was reconstructed with a modern façade and interior. The theatre has an active company producing plays by modern Serbian and foreign playwrights, while the National on Republic Square tends more towards a classical repertoire.

Across the road from the theatre are Flower Square and the beginning of Njegoš Street. This plot was designated as a parcel of land to be developed as a market in 1843 when the first steps were taken to extend Belgrade further beyond Terazije and into the district of Vračar. In the last quarter of the nineteenth century and particularly after the announcement of Serbia’s transformation into a kingdom this district became the elite residential area. The new middle classes of merchants, professional groups, army officers and state officials moved here and built large town houses. The area bordered by King Alexander Boulevard and King Milan Street as far as St. Sava’s Church provides many examples of rapid urban development.

The people who moved into the district proved to be the kind of articulate middle class who would get things done for themselves. They formed the Society for the Beautification of Vračar (Društvo za ulepšavanje Vračara) in 1884, and one of the amenities they pressed for was a covered market at Flower Square of the kind beginning to appear in western towns. They got their wish, and the first stand for fiacres in Belgrade was also put here in 1886 in order to help speed up the journey time to the city centre. The bottom of Njegoš Street by Flower Square was used as a taxi rank for more modern vehicles until the beginning of the twenty-first century when the area was pedestrianized.

The house at 1 Njegoš Street has the name of the society dedicated to improving Vračar inscribed at the top, and in the hallway, just inside the front door, are four plaques on the wall listing the names of honoured (and deceased) members. It is a list of people from a wide variety of professions giving a sociological insight into that new elite: café owners, retired generals, a butcher, civil servants, a judge and many others. Many of the houses at the beginning of the street have recently been converted into small bars with outside seating, or expensive boutiques. Even so, there are still traces of the previous atmosphere. The house at no. 11 is highly decorated with many original figures in relief on the front. Behind the modern appearance at ground level facing the street, the small workshops of some craftsmen are still to be found in the back courtyards, indicated by old signs above the entrances advertising a cobbler, watch mender, or bag repairer.

Flower Square itself has gone through various transformations and eventually became an enclosed supermarket with some flower stalls in front. The supermarket was the first self-service outlet in Belgrade, introduced by the communists during the period when the country was going through radical reform and moving away from the Soviet model of state socialism, and a sign of the gradual westernization of Yugoslavia from the early 1960s. In the early twenty-first century the supermarket became a showroom for expensive cars. There has, however, remained one constant on this little square. In front of the car showroom stands an oak tree, under the protection of the state, which has been here on this spot as a witness to all change since the time of Knez Miloš.

ALACE

C

OMPLEX

There are two palaces standing side by side on King Milan Street. The first residence on this site was built by the leader of the State Council under Knez Miloš, Stojan Simić, in the 1830s, as Terazije was going through its initial building programme. His house stood just behind the palaces visible today, further back from the line of the road in the park. Knez Alexander Karađorđević bought Simić’s house in 1846 for his own use.

In moving here, the new knez made a symbolic gesture by leaving Ottoman Belgrade for the site of the new development. The building, known as the Stari konak or the Old Residence, was used as private accommodation by all the nineteenth-century rulers of Serbia and housed administrative offices. It also was the place where princes and kings hosted celebrations and official gatherings, entertaining foreign guests and Belgrade’s elite society. It was decorated in an entirely European style with parquet floors and brightly-lit candelabras quite unlike more traditional tastes in furnishing.

Slobodan Bogunović remarks on the modernizing influence it had on the city:

The running of the Old Residence in terms of palace protocol, internal furnishings and organization of rooms, represented a complete contrast with those of Miloš Obrenović in the ruler’s first Belgrade residence. It was the result of social evolution and was used to encourage the adoption of cultural models other than the national. The ruling family introduced completely new types of social amusement and concepts of behaviour, which were passed on to the more prominent citizens through their required attendance at palace balls, official receptions, tea parties, concerts and other celebrations. These new forms of social ritual representing European influences slowly spread from the palace through Belgrade society.

Not all events in the Old Residence were to be pleasurable. In 1903 King Alexander Obrenović and Queen Draga were assassinated here, and Peter Karađorđević had it demolished the following year.

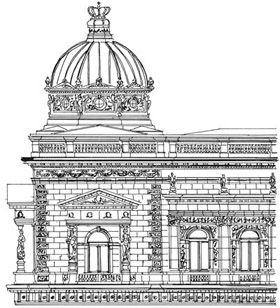

Milan thought the Old Residence inappropriate for official occasions when he became king, so he built a new palace in 1884. Having decided that a more impressive building was required, Milan hired the services of the architect who had built the National Theatre a few years before. The result was a stage on which to play his role. The grandiose palace provided offices and reception rooms, while he and his family continued to live in the smaller building behind. More modern public and government buildings were opened around the palace, giving the district an air of importance compared to the earlier and smaller constructions around the Town Gate—which lost its place as the focal point of the Serbian capital.

King Peter Karađorđević began work on another palace just across the park from the one built for King Milan. The result is a more sombre but statesman-like design. Construction began in 1911 but was interrupted by the war during which the unfinished building was damaged. His successor, King Alexander, finally moved into the new royal residence in 1922, where he remained until his death in 1934. Afterwards, with Alexander’s son still a minor, Prince Paul ruled as regent, but rather than live in the palace he used it for different purposes and from 1936 it was the Museum of Prince Paul (Muzej Kneza Pavla).

The royal residences have since become known as the Old Palace (Stari dvor), situated toward Terazije, and New Palace (Novi dvor), next to Andrić Crescent. After the Second World War Yugoslavia was declared a republic from which the former royal family was banned and their property nationalized. The Old Palace has become the building for the Council of the City of Belgrade, while the New Palace is the office of the President of Serbia.

ERFORMING

A

RTS

Two types of early music and theatre had developed in medieval Serbia, one in the life of village communities and another in the life of religious orders. In villages the performers of oral ballads formed a troubadour class, singing and playing in public places and on other occasions to smaller audiences. The performances were centred on the single player for whom no special building, stage or any kind of infrastructure was needed. There was also an embryonic secular theatre, but like most other public manifestations of Serbian culture it disappeared with the conquest of the region by the Ottoman Empire.

Church art was not entirely cut off from secular activities. Yet the Church held a position of social and moral authority, which it exercised partly through its special rituals that maintained some distance from the everyday experience of the bulk of the population. This distance was an integral part of the mechanism that perpetuated its authority, allowing the Church and its representatives to minister to their flock but not be absorbed by them. The Church fostered what might be regarded as its own theatre of heavenly beauty, pageantry and splendour in divine service, which was accompanied by its own kind of music and chanting originating in the traditions of the Byzantine Empire.

Devotional music played an important part in the early Church but did not survive as performance art in public. Developments in these fields became possible again for those Serbs who fled north at the end of the seventeenth century and established small semi-autonomous communities in the borderlands of the Habsburg Empire. Sremski Karlovci was the centre of the Serbian Church and, therefore, of cultural life among the Serbs of Vojvodina. The Byzantine traditions of church singing and music were practised here and later exported south over the border into Serbia. Secular music as performance art, on the other hand, was slow to develop. The centres of European music were in the West or Russia, and their influence could only spread through foreigners who were attracted to work in Belgrade, or by sending students to be educated abroad.

One of the first promoters of music in Belgrade was Davorin Jenko (1835–1914) from Slovenia who was responsible for musical arrangements at the National Theatre for some thirty years. Stevan Stojanović Mokranjac (1856–1914) played a highly important role as a composer, an arranger of music and in particular as one of the founders of the Belgrade Choral Society of which he was director. Blending the traditions of both folk and church music, he enjoyed much success at home and abroad with tours of Bulgaria, Croatia, Montenegro, Turkey, Russia and in 1899 Berlin, Dresden and Leipzig. The Belgrade Opera was founded in 1920 and the Belgrade Philharmonic in 1923.

Stefan Hristić (1885–1958) studied in Leipzig, Paris, Moscow and Rome before taking a leading part in promoting the musical life of the city as a director of the Opera, a conductor and composer. The efforts of people like him received an unexpected boost after the Russian Revolution of 1917 since Belgrade was one of the destinations for many fleeing the Bolsheviks. The refugees included singers and musicians who were only too willing to contribute their talents to the benefit of the host community. Performances of ballets, operas and concerts were supported in the city, staged by permanent companies and with frequent touring groups from abroad. It was common practice among the new middle class to hire private tutors for learning foreign languages and playing musical instruments. These activities were regarded as simply part of what every child should receive in order to be fit for adult life. A Czech pianist and teacher of music, Emil Hajek (1886–1974), came to Belgrade to work in the Stanković Music School, and in the 1930s was one of the founders of the city’s Academy of Music (Muzička akademija), which offered higher level instruction in all areas of playing, singing and composing and helped to bring musical arts to an international level.