BELGRADE (32 page)

Authors: David Norris

The area known as Košutnjak begins just to the south of Senjak. It is thickly wooded parkland with mixed deciduous and evergreen trees spreading up the hill away from the valley floor of Topčider. In the nineteenth century it was known as a hunting ground, košuta being the Serbian word for a hind or a doe. It covers a substantial area and has retained a rather wild appearance. People come here to have a picnic or go walking. Residential areas have since sprung up around Košutnjak, too, so it is no longer on the very periphery of Belgrade, yet building within the park area is controlled to keep it a green oasis. The air is much clearer than closer in to the city where there is a concentration of exhaust fumes and noise. Knez Mihailo Obrenović was assassinated in Košutnjak on 29 May 1868. The spot is commemorated with a simple monument, which is inappropriately small and hidden away, really deserving a more prominent and visible place. A railway line marks the boundary between Košutnjak and the Topčider valley.

Topčider valley nestles in the middle of the area bordered by Dedinje, Senjak and Košutnjak, down the hill from the Topčider Star. The area is known for its very pleasant microclimate, enjoyed by the rulers of Belgrade, whether Ottoman or Austrian, who escaped business in town and came here for picnics, hunting or country parties. In times of war it was a strategic point for armies attacking the city where they could put up camp in relative safety, separated by the hill from the defenders’ guns. The valley also gave control of major approaches to Belgrade from the south. The Turks made use of the area when taking the city in 1521, and later Karađorđe during the First Serbian Uprising.

Miloš Obrenović decided to build a small palace complex in the bottom of the valley for himself after receiving the

hatti-sherif

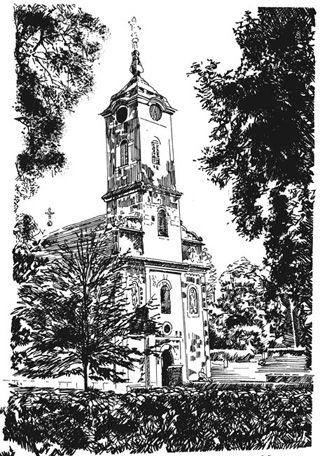

of 1830. The konak, or residence, intended for use by the church next door, was the first building to go up in 1830–32, constructed in a traditional Balkan style. The church, dedicated to the apostles Peter and Paul, was built over the next two years and designed according to more western taste with a tall bell tower like the Cathedral church in Belgrade, but on a much smaller scale. The prince’s own residence, Konak kneza Miloša, was sited close by and was also constructed between 1832 and 1834 in a typical Balkan style of architecture. These buildings still stand today, except that Miloš’s konak now houses a museum with exhibitions about the Serbian uprisings against the Turks.

After his exile abroad, Miloš took up residence here again in 1859, and after his death the Obrenović rulers continued to use it as a summer house. Other workshops, a military store and a garrison were built, but most of the area was developed as a park. Miloš did not want a defensive fortification on this spot and he modelled his residence on the kind of environment that the ruling families in Western Europe were then making for themselves. One French visitor, quoted by Bogunović, remarked that the residence at Topčider was “the Versailles of the Serbian Princes”.

EINTERPRETING THE

P

AST

Literature in the 1980s became obsessed with looking at the past in new ways. The taboos of Tito’s time gradually gave way to a much bolder approach to recent history. Even so, the League of Communists of Yugoslavia was not prepared to allow creative artists simply to express any views or images without a struggle. The Serbian poet Gojko Đogo found himself in court for his collection titled

Woolly Times

(Vunena vremena, 1982) in which he provided very unflattering sketches of the late president himself. He spent a period in prison before an early release on conditional discharge after public protests at his treatment.

The Croatian League of Communists published a report in 1984,

The White Book

(Bijela knjiga), criticizing contemporary artists who allowed themselves too much liberty. The 237–page document detailed instances in which it was felt that novels, plays, films, aphorisms and literary criticism were spreading messages hostile to the regime. By far the greatest amount of offending material was taken from Serbia with considerably less from Slovenia and Croatia. The report stated that some criticism in recent times had gone beyond the bounds of acceptability and had attacked “the very direction of Yugoslav social development and the basis of the economic and political syste”. The themes to which the party hierarchy objected in particular were stories about the prison island Goli Otok, narratives rewriting the story of the Partisan struggle and stories whose bleak pictures of the contemporary world indicated that not all was well with socialism in Yugoslavia. Authors were publishing work that questioned assumptions about the past and the present—“open attempts to devalue the revolution and its achievements in the name of demystification”.

The

White Book

was correct in its basic assumption that writers in 1980s Serbia were re-assessing the story of communism in Yugoslavia. This is not to say that all were dissidents or intent on pulling the regime down; for many it was an attempt to open a debate on the nature and direction of contemporary society. This kind of Serbian writing, with its concentration of talent in Belgrade, was epitomized by one member of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Predrag Palavestra, as “critical literature”. Writers were interested in the process that brought the communists to power, the consequences of their policies and the gap between official versions of history and what was preserved in folk memory from those times.

The novelist Slobodan Selenić took this topic as the theme for his address to a conference held in Belgrade in June 1990. Participants at the conference from the Serbian and Swedish Academies were examining the responsibility of science and the role of intellectuals in contemporary society. Selenić spoke about mainstream tendencies in the modern Serbian novel and compared them to the fate of historiography as an academic discipline. He described how history under the communists in Yugoslavia ossified, how it “ceased being the branch of knowledge that records and explains past events”. Instead, it became a series of convenient slogans and assumptions about what happened. History, the academic subject entrusted with the responsibility of investigating what has made us what we are today, was emasculated. For decades after the end of the Second World War the primary task of the historian had been to reinforce the place and prestige of the communist movement in Yugoslavia. Hence, Selenić insisted that only the imaginative scope of literature was free to take a fresh look at Serbian history. Novelists had the task to exhume and disturb the ghosts of the past, to offer alternative visions of what happened, to take on the responsibility of confronting accepted wisdoms. For some Belgrade novelists, the story of their city during the war and its subsequent liberation was one of those topics that had not received the treatment it deserved.

The Partisan novel was typically set in the mountains and among the small villages of provincial Yugoslavia while German and Italian forces were in possession of most major towns and communication routes. Consequently, there were very few stories about the war set in Belgrade. One exception was the novel

The Poem

(Pesma, 1952) by Oskar Davičo (1909–89)—except that the plot offers a standard view of Belgrade as a corrosive and corrupting environment. Then Aleksandar Đorđević (1924–2005) directed the 1974 film

The Written-off

(Otpisani) about a group of young communists in Belgrade fighting the Germans and bringing the guerrilla war into town, followed by a sequel two years later,

Return of the Written-off

. Both films were transferred to the small screen and became very popular television series.

The story of war-time Belgrade, however, received a much more vigorous re-interpretation in two novels, translated into English: Slobodan Selenić’s

Fathers and Forefathers

(Očevi i oci, 1985) and Svetlana Velmar-Janković’s

Dungeon

(Lagum, 1990).

The story of

Fathers and Forefathers

is told by two characters, the married couple Stevan and Elizabeth Medaković. Stevan meets the English girl Elizabeth in Bristol when he goes to study at the university there, taking her back to Belgrade as his wife in 1925. The novel covers their life together from when they meet to some forty years later when they are both alone in their rooms on the second floor of 52 Knez Miloš Street.

The novel dramatizes a series of clashes of different cultures as Serbs and English, parents and children, communists and non-communists, traditional and modern worlds, rub up against one another, repelling and attracting. Elizabeth is particularly struck by the contrasts she experiences in Belgrade. One side is characterized by poverty, backwardness and cruelty. On arriving at the Sava quay by boat at the end of their long journey from England in 1925, she is frightened by the sudden appearance of men in rags racing through the mud to fight over their bags and earn a tip. She rails against the way in which the draymen whip their horses on steep streets and slippery cobbles. This is the barbaric side of Belgrade, which she sums up as “the Orient”. The other side of her life is epitomized by Stevan, who lectures at the Faculty of Law, and his friends, all of whom are highly educated and cultured people. They are knowledgeable about world affairs and some are amateur chamber musicians who meet regularly to play for their own enjoyment. This is the civilized, European Belgrade.

Selenić’s novel allows ample opportunity for reflection on Belgrade society and Serbian culture. At the time of its publication, however, readers were more alert to its picture of life in the city when the communists arrive in 1944. For Stevan and Elizabeth, the Partisans are hardly liberators, and Stevan recalls—in contradiction to the regime’s propaganda—how the citizens of Belgrade knew very little about the resistance movement during the occupation since its distant operations were of little relevance to the daily grind of surviving the war in the city.

Mihajlo, Elizabeth’s and Stevan’s son, is intensely drawn to the young comrades from the hills and villages of Bosnia and Serbia with whom he comes into contact. He invites them into the family home which they use to paint banners and posters to take on demonstrations in support of Tito. As they prepare their materials they spill paint and carelessly put their muddy boots on furniture. Stevan describes how “I clenched my teeth, kept my silence and watched how the Huns and Visigoths devastated my home from one day to the next.” They have, he says, the “spontaneity of jungle creatures” unconscious of what they are doing “because they knew no order”. Selenić also draws into his fictional world the names of the party hierarchy whom Stevan meets and who force him to work for them because they want to make use of his legal expertise. He calls that period “those ugly and perilous times”.

The worst, however, is yet to come. Mihajlo in his euphoric support for the Partisans is sent, along with many other young people from Belgrade, to fight on the Sremski Front, the final battle to push the enemy out of the country. The battle is a disaster, where many of the recruits, poorly trained and badly armed, are killed. Mihajlo dies and Stevan brings his body home for burial. His death holds a symbolic significance, for something in Stevan and Elizabeth dies with him, destroying any chance of future happiness together.

Svetlana Velmar-Janković’s novel

Dungeon

was published in 1990, five years after

Fathers and Forefathers

. The work is presented as if the diary of Milica Pavlović, wife of Dušan Pavlović, a respected professor at Belgrade University. In her recollections she depicts the liberation of Belgrade and its effects as a complete break with the city’s past. The arrival of the Partisans sets off a train of events based on betrayal, execution and requisition. As the city is liberated, the Partisans arrest Dušan for being a collaborator. During the war he accepted a post in the quisling government, which gave him responsibility for refugees, and he was able to save the lives of many Serbs who would otherwise have been killed by the occupying forces or by the Ustaše. In his opinion his actions were honest and honourable, but his view is not shared by the new authorities and he is led away. Milica later discovers that he has been executed along with others accused in the mass trials held at the end of November 1944. She is devastated by the news, but this is not the end of her story.

Dušan is arrested in the presence of people both he and Milica know.

One of them is the caretaker of their building in the district of Dorćol, a man who would always help the wealthy families who live there, until the revolution comes and he joins the fight out of weakness. Another is the son of the Armenian grocer whose shop was on the corner of the street. He reappears in the city as a Partisan officer determined to establish the new ideological order. Their sumptuous flat is immediately divided. Milica and her two children are allowed to live in the smaller portion, while the larger area is given to their maid, now known as Comrade Zora. She is one of the lucky few from a small village near Šid whom Dušan managed to save during the war and whom he brought home to live with them. She now turns on her former benefactors and directs the soldiers to the most valuable paintings in the flat, which are confiscated. Milica has difficulty in obtaining food and fuel, and cannot work as she is regarded as an enemy of the people. Eventually, she is able to get a job as a translator, although she is not allowed to sign her work with her own name. She is a person without a past or a present and barely exists in this brave new world.