Battleship Bismarck (31 page)

Read Battleship Bismarck Online

Authors: Burkard Baron Von Mullenheim-Rechberg

In the afternoon of 24 May, Lütjens learned from Group West, which had been informed by a Spanish source,

*

that the

Renown, Ark Royal

, and a

Sheffield-class

cruiser—in other words, Force H—had sailed from Gibraltar the previous evening, course not known. What Group West did not know, and therefore could not tell Lütjens, was that these ships had left Gibraltar on a convoy-escort mission but had subsequently been redirected against our task force. Lütjens would have assumed the latter objective, anyhow. Whether or not our B-Dienst team gave him any more information about the enemy that same afternoon, I do not know.

It was not until around noon the next day that the Fleet Commander told us anything at all about the drastic measures the British were taking, and then he told us only in general terms. Up to that time every man had made up for the lack of information by using his own imagination. I recall that my imaginings were very vague. It was just as well that some things were not known. That way, we could still have our moments of hope and, should a critical situation arise, we would deal with it, as before, to the best of our ability. Our young crew was inherently optimistic and, surely, the preservation of optimism for as long as possible could only be to the good. An exact

awareness of the enemy armada being assembled would have had anything but a healthy effect on the ship’s morale.

Midnight gave way to Sunday, 25 May, Admiral Lütjens’s birthday, and over our loudspeaker system the ship’s company offered him congratulations. Darkness had fallen and our shadowers, the

Suffolk, Norfolk

, and

Prince of Wales

, were once again forced to rely on the

Suffolk’s

invaluable radar. Since late the day before, all three of them had been off our port quarter, the

Suffolk

at times being as little as ten nautical miles away from us.

*

Lütjens, undoubtedly having been informed that our listening devices and radar showed no hostile ships to starboard, evidently decided it was high time to try to break contact. Shortly after 0300, we increased speed and turned to starboard. First, we steered to the west, then to the northwest, to the north, and, when we had described almost a full circle, we took a generally southeasterly course in the direction of St. Nazaire. I was not aware of these maneuvers, either because I was in my completely enclosed control station and in the darkness did not notice the gradual turn, or because I was off duty at the time. The maneuver carried out the intention that Lütjens had radioed to the Seekriegsleitung the previous afternoon and that had grown increasingly urgent, “Intention: if no action, to attempt to break contact after dark.”

Fate seemed to have a birthday present for the Fleet Commander. The

Suffolk

, steering a zigzag course as a defense against possible U-boat attacks, had become accustomed to losing contact with us when she was on the outward leg of her course and the range opened, but regaining it as soon as she turned back towards us. At 0330 she expected to regain the contact she had lost at 0306. She did not.

Lütjens’s great chance had come! But he didn’t recognize it. He must have believed that, despite his maneuvers, the

Bismarck’s

position was still known to his shadowers. He cannot have been aware that by transmitting messages he might be enabling the enemy’s direction finders to renew contact with her. After all, his position had been known to the

Suffolk

and

Norfolk

ever since he first encountered them more than twenty-four hours earlier, and radio signals, even long ones, would not really tell the enemy anything new about the position of his flagship. Therefore, he saw no reason for maintaining radio silence, or even any need to use the Kurzsignalverfahren,

*

which at that date was still immune to direction-finding.

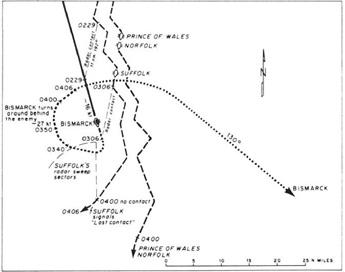

From 0229 to 0406, German Summer Time, on 25 May. The

Bismarck’s

changes of course that led to the loss of contact. (Diagram courtesy of Jürgen Rohwer and Vice Admiral B. B. Schofield.)

It cannot be definitely determined, but this must be how he thought because at around 0700 he radioed Group West, “A battleship, two heavy cruisers continue to maintain contact.”

†

When the

Suffolk

was unable to renew contact with the

Bismarck

, she and the

Norfolk

, going on Wake-Walker’s assumption that the

battleship had broken away to the west, changed course in an attempt to pick her up again. Therefore, by 0700, they had been steaming for several hours in first a southwesterly then a westerly direction. If the

Suffolk’s

radar, with its range of 24,000 meters, could not regain contact with the

Bismarck

at 0330, what chance did it have of doing so at 0700, by which time the

Bismarck

had been steaming for hours in a southeasterly direction? As for the battleship whose presence Lütjens reported, around 0600 the

Prince of Wales

turned to a southerly course in compliance with orders that she join the

King George V.

Therefore, she also had moved too far away from the

Bismarck

to know the latter’s position at 0700.

Shortly after 0900 Lütjens radioed to Group West:

Presence of radar on enemy vessels, with range of at least 35,000 meters,

*

has a strong adverse effect on operations in Atlantic. Ships were located in Denmark Strait in thick fog and could never again break contact. Attempts to break contact unsuccessful despite most favorable weather conditions. Refueling in general no longer possible, unless high speed enables me to disengage. Running fight between 20,800 and 18,000 meters. . . .

Hood

destroyed by explosion after five minutes, then changed target to

King George V

, which after clearly observed hit turned away making smoke and was out of sight for several hours. Own ammunition expenditure: 93 shells. Thereafter

King George

accepted action only at extreme range.

Bismarck

hit twice by

King George V.

One of them below side armor Compartments XIII–XIV. Hit in Compartments XX–XXI reduced speed and caused ship to settle a degree and effective loss of oil compartments. Detachment of

Prinz Eugen

made possible by battleship engaging cruiser and battleship in fog. Own radar subject to disturbance, especially from firing.

†

In the first four sentences of this signal Lütjens reported the perplexing new dimensions that during his passage of the Denmark Strait he had seen looming for the operation of our heavy ships in the Atlantic.

In the course of the past hours Group West got a completely different and correct impression of the scene around the

Bismarck.

Reports sent out by the British shadowers and received by Group West after the dissolution of our task force had, at first, shown some confusion on the part of the enemy. They were still reporting contact with both

the

Bismarck

and

Prinz Eugen

at 2230, 24 May, in spite of the fact that the ships had separated shortly after 1800. From 2230 until 0213 the next day, they reported contact with the

Bismarek

alone, then their reports ceased. When several hours passed and no more reports of contact were picked up, it seemed clear that contact had been broken, and at 0846 the Group signaled Lütjens: “Last report of enemy contact 0213

Suffolk.

Thereafter continuation of three-digit tactical radio signals but no more open position reports. Have impression that contact has been broken.”

How incomprehensible it must have been for Group West, after 0900, to receive two radio signals from Lütjens reporting that the enemy was still in contact.

The

Bismarck’s

signals appeared equally incomprehensible to those aboard the

Prinz Eugen

, which was now far distant but still able to pick up her transmissions. Their shipboard B-Dienst team had long realized from decoding British radio traffic that the British had lost contact with the

Bismarck.

The painful certainty grew on them that this loss of contact had escaped the

Bismarck

and that she had placed herself in danger, great danger, of being located by radio direction-finding. But why?

Why did he still believe his position was known, when even Group West had the impression that contact had been broken? There are four conceivable explanations, in one of which, or in a combination of which, the answer must lie.

First, perhaps the

Bismarck

was still detecting enemy radar pulses, and that made Lütjens think that contact had been maintained. Besides her three radar sets, the

Bismarck

had a radar detector, a simple receiver designed to pick up incoming pulses of enemy radar. Upon receiving such pulses, the detector allowed the wavelength, the frequency and strength of the pulse, and the approximate direction of the sender to be determined. Precise direction-finding, however, was not possible. If such incoming pulses were actually still being picked up at 0700 that day, they could not have been useful to the originating ships, since the pulse reflections had to return to the shadower’s radar transmitter to be registered. For if, as previously mentioned, the range had already become too great for the reflections from the

Bismarck

to return to the

Suffolk’s

radar at 0330, because of the ships’ diverging courses, by 0700 the range must have been much too great. Possibly the

Bismarck’s

operators were picking up weak radar pulses beyond effective range of the radar transmitter—in the case of the

Suffolk

, 22,000 meters. Merely to receive a pulse, however, does not

necessarily mean that the sender has fixed the target’s position. Radar operators must be especially careful to observe and evaluate the strength of an incoming pulse. The ability to do that requires expert training and practice, and whether the

Bismarck’s

radar operators had those qualifications, I cannot say. I am not an expert in this area. In any case, it should be borne in mind that all radar was still in its infancy and there was not much experience to go on. I leave the question open. I think that by 0700 on 25 May our distance from the

Suffolk, Norfolk

, and

Prince of Wales

must have been too great for us to pick up even weak pulses from them. Moreover, the three erstwhile shadowers assumed that the

Bismarck

had turned to the west and therefore adjusted their search patterns in that direction. Would they not have used their radar to search the area ahead of them, to the west, rather than behind them, to the east, where the

Bismarck

really was? It is difficult for me to believe that radar pulses were still being picked up by the

Bismarck

at 0700.

*

Second, the interception of enemy radio traffic might have given Lütjens the impression that his position was still known. It may be that the signals of his shadowers were still so strong that it did not occur to him that there had been any change in their proximity. The possibility is purely theoretical. Nothing concrete concerning it has come to my attention.

Third, it is possible that during these hours our B-Dienst team gave Lütjens information that he took or had to take as an indication that the enemy was still in contact. Had the B-Dienst misinterpreted British tactical signals or operational transmissions? Did it play any other role in this connection? That possibility cannot be excluded.

Fourth, Lütjens might have been so deeply under the spell of what he took to be the superiority of British radar that he was no longer able to imagine anything else. Can the two radio messages he sent on the morning of 25 May therefore have a purely psychological explanation, his feeling of resignation? As stated, it is conceivable. In view of the first four sentences of his second signal, it is even probable.

To draw a convincing conclusion from four such diverse alternatives is difficult. I would, however, like to exclude the first. The second and third I can neither assert nor exclude. Not having any direct knowledge of how Lütjens reacted during the most critical phase of the operation so far, from the beginning of the pursuit by the

Suffolk

and

Norfolk

in the Denmark Strait to the morning of 25 May, I am not in a position to transfer the fourth alternative from the realm of the conceivable into that of the believable. In my view, a veil must remain over the reason why Lütjens supposed that the

Bismarck’s

position was known and therefore did not regard the enemy’s ability to take a fix on a radio signal as a new and serious danger to his ship.

After 1000 the

Bismarck

did observe radio silence, and Group West then realized that the signal it sent to Lütjens at 0846 had shown him his error concerning enemy contact. But his attempt to correct his mistake by maintaining radio silence was not enough to repair the damage done by the dispatch of his two radio signals.