Battleship Bismarck (26 page)

Read Battleship Bismarck Online

Authors: Burkard Baron Von Mullenheim-Rechberg

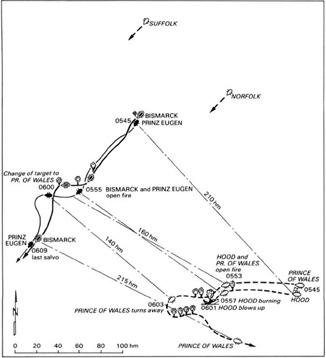

From 0545 to 0609, German Summer Time, on 24 May. The battle off Iceland. (Diagram courtesy of Paul Schmalenbach.)

The

Prince of Wales

took four 38-centimeter hits from the

Bismarck

and three 20.3-centimeter hits from the

Prinz Eugen.

One 38-centimeter shell struck her bridge and killed everyone there except the captain and the chief signal petty officer. Another put her forward fire-control station for the secondary battery out of action, and a third hit her aircraft crane. Number four penetrated below the waterline, did not explode, and came to rest near one of her generator rooms. Two 20.3-centimeter shells went through her hull below the waterline aft, letting in some 600 tons of water which flooded several aft starboard compartments, including a shaft alley; the third entered the shell handling room of a 13.3-centimeter gun and came to rest there, without exploding. One of the crew of this mount instantly carried the shell to the railing and threw it overboard. Besides the damage done by these hits, the

Prince of Wales

was suffering from increasingly frequent trouble with her main turrets, which had been in operation for only two months, so that she was able to get off scarcely a salvo with its full load of shells.

The

Bismarck

has turned to starboard of her cruiser consort. Her guns trained astern, she has just fired a salvo. The smoke from a previous salvo and a column of water from one of the

Prince of Wales’s

14-inch shells to the right. The splash of a major-caliber projectile could easily reach seventy meters in height. (Photograph courtesy of Paul Schmalenbach.)

It was in the stars that the shell that struck the bridge of the

Prince of Wales

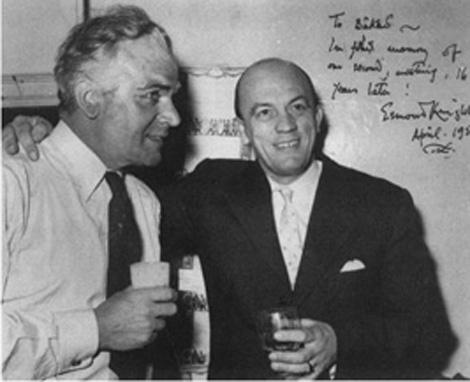

would not explode until it had passed through, a fact that later brought me the friendship of one of its victims. Lieutenant Esmond Knight, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, an actor by profession and a painter and ornithologist by avocation, was keeping lookout through a pair of German Zeiss binoculars. His station was in the unarmored antiaircraft fire-control position above the bridge, and he was protected only by his steel helmet. He heard something like “a violently onrushing cyclone,” then someone said, “Stretcher here, make way.” He had the feeling that he was surrounded by corpses and he smelled blood. People were approaching him and asking, “What happened to you?” He looked in the direction of the voices and saw nothing—a shell splinter had blinded him. In 1948, after a visitor to Germany brought me greetings from him, he wrote me, “I was blind for a year, but now I am back in my old profession at the theatre, which makes me very happy.” In 1957 I was a surprise guest in the episode of the BBC’s television program “This is Your Life” that was devoted to Esmond Knight. That is when we met for the first time, and we have been friends ever since.

To the left, the wreckage of the

Hood

still burns as the

Prince of Wales

comes under fire by the

Bismarck.

Between the

Prince of Wales

and the burning remains of the

Hood

are splashes from the

Prince of Wales’s

shells, which fell hundreds of meters short. (Photograph courtesy of Paul Schmalenbach.)

But back to the

Bismarck.

Today, I greatly regret that, especially from this time forward, I was not a party to Lütjens’s deliberations, his conferences within the fleet staff, and his conversations with Lindemann, and did not even have any means of hearing about them secondhand. Nothing of them reached me in the after fire-control station. I can only record the statements of survivors to the effect that Lütjens and Lindemann had a difference of opinion regarding breaking off the action with the

Prince of Wales.

Apparently, Lindemann wanted to pursue and destroy the obviously hard-hit enemy, and Lütjens rejected the idea. Lütjens may have feared that if he continued the action he would be drawn in a direction from which other heavy British units might be advancing. German aerial reconnaissance had not, at that time, provided him with accurate information on the disposition of the British Home Fleet. Therefore, he would be running the risk of getting into more action, using up more ammunition, and, of course, having his own ships damaged—none of which prospects he could have welcomed in view of his principal mission, “war against British trade.” He would have viewed it as necessary to forgo the destruction of another British battleship, which must have been tempting to him also. But the chances are that his reserve prevented him from explaining his decision to Lindemann. “Differences of opinion” generally result in arguments and, according to one survivor, there was an argument between Lütjens and Lindemann about breaking off the action. It is not clear what the survivor meant by an argument, but it is highly unlikely that there were loud words in the presence of third parties. In view of the personalities of the men involved, it seems certain that whatever took place would have been conducted with military formality. The only thing definite about this is that someone overheard an officer of the fleet staff telling Fregattenkapitän Oels over the telephone that apparently Lindemann had tried to persuade Lütjens to pursue the

Prince of Wales.

According to other reports, there was “heavy weather” on the bridge for a while. It seems likely that the “argument” was more evident in the atmosphere than in an exchange of words.

*

Former Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve Lieutenant Esmond Knight was blinded by a German hit on the

Prince of Wales

during the battle off Iceland. An actor by profession and an ardent amateur painter and ornithologist, he was able to return to his old profession after he regained his sight. This picture shows author’s meeting with Knight in London in 1957 on the occasion of the BBC Television program “This Is Your Life” devoted to him. (Photograph courtesy of the

Daily Express

, London.)

In any event, the men below found it absolutely incomprehensible that, after the destruction of the

Hood

, we did not go after the

Prince of Wales.

They were upset and disappointed. Upon the report of the battle off Iceland Hitler expressed himself to the same effect. “If now,” he said to his retinue, “these British cruisers are maintaining contact and Lütjens has sunk the

Hood

and nearly crippled the other, which was brand new and having trouble with her guns during the action, why didn’t he sink her, too? Why hasn’t he tried to get out of there or why hasn’t he turned around? That’s really what he was thinking of. But then he would have run into the arms of the Home Fleet.”

The battle off Iceland was over and we had used astonishing little ammunition: the

Bismarck’s

38-centimeter guns had fired 93 shells and the

Prinz Eugen’s

20.3-centimeter guns had fired 179. Many shells fell close to the

Prinz

, but she was not hit; the

Bismarck

received three 35.6-centimeter (14-inch) hits. My action station was high up and in the tumult of the battle, I was not aware of any incoming hits, but the men in the spaces below found them easily distinguishable from the firing of our own guns. “Suddenly,” a petty officer (machinist) wrote of our first hit from the

Prince of Wales

, “we

sensed a different jolt, a different tremor through the body of our ship: a hit, the first hit!”

That first hit, forward of the armored transverse bulkhead in the forecastle, passed completely through the ship from port to starboard above the water line but below the bow wave. It damaged the bulkheads between Compartments XX and XXI and Compartments XXI and XXII and left a one-and-a-half-meter hole in the exit side. It also ripped up several wing and double bottom tanks. Before long we had nearly 2,000 tons of seawater in our forecastle.

The second hit struck beneath the armored belt alongside Compartment XIV and exploded against the torpedo bulkhead. It caused flooding of the forward port generator room and power station No. 4, and shattered the bulkheads between that room and the two adjacent ones, the port No. 2 boiler room and the auxiliary boiler room. Later, it was discovered that this hit had also ripped up several of the fuel tanks in the storage and double bottom.

The third shell severed the forepost of one of our service boats, then splashed into the water to starboard without exploding or doing any other apparent damage. The crew of an unarmored antiaircraft gun nearby was very lucky; although the hit sent splinters of the boat flying in every direction, none of them was injured. Happily, no one was hurt by any of the hits we took at this time.

Our damage-control parties

*

and machinery-repair teams made a detailed inspection of the damage that had been done by the two serious hits and set about making what repairs they could.

Forward, the anchor windlass room was unusable and the lower decks between Compartments XX and XXI were flooded. Consequently, the bulkhead behind Compartment XX was being subjected not only to the pressure of static water, but, on account of the big hole in our hull, to that created by our forward motion. To keep it from giving way, a master carpenter’s team shored it up while the

action was still going on. After the action, a work party led by the second damage-control officer, Oberleutnant (Ingenieurwesen) Karl-Ludwig Richter, attempted to enter the forward pumping station through the forecastle in order to repair the pumps so that the contents of the forward fuel storage tanks could be transferred to the service tanks near the boiler rooms. But the pumps in Compartment XX were under water, those in Compartment XVII did not help much, and the valves in the oil lines in the forecastle were no longer serviceable. When an effort to divert the oil via the upper deck also failed, we realized that the 1,000 tons of fuel in the forward tanks were not going to be any use to us. Lütjens turned down Lindemann’s suggestion of heeling the ship first to one side and then the other and reducing speed in order to allow the holes in our hull to be patched. Later, however, we did slow to 22 knots for a while, which at least allowed matting to be placed over the holes, and the flow of water into the ship was reduced.