Battleship Bismarck (29 page)

Read Battleship Bismarck Online

Authors: Burkard Baron Von Mullenheim-Rechberg

We entered another heavy rain squall. Visibility declined and Lütjens, deciding that the moment had come for us to leave the

Prinz Eugen

, gave the signal, “Execute

Hood.

” It was about 1540. The

Bismarck

increased speed to 28 knots and turned to starboard, in a westerly direction. But our breakaway did not succeed. We were out of sight for a few minutes, than ran out of the squall, right back into the sight of one of our pursuers. We simply completed a circle and, coming up from astern at high speed, rejoined the

Prinz Eugen

some twenty minutes after we’d left her. By visual signal, we told her,

“Bismarck

resumes station here, as there is a cruiser to starboard.” Almost three hours later, when we were in a fog bank, Lütjens repeated the code word

Hood.

We executed the same maneuver as before and separated ourselves from the

Prinz Eugen

, this time for good. Turning first to the west and then to the north, we ran into a rain squall, pretty confident that the enemy had not observed the dissolution of our task force. The second gunnery officer of the

Prinz Eugen

, Kapitänleutnant Paul Schmalenbach, later described the parting:

The signal to execute the order for the two ships to separate is given for the second time at 1814. As the

Bismarck

turns away sharply, for the second time, the sea calms. Rain squalls hang like heavy curtains from the low-lying clouds. Watching our “big brother” disappear gives us a melancholy feeling. Then we see him again for a few minutes, as the

flashes of his guns suddenly paint the sea, clouds, and rain squalls dark red. The brown powder smoke that follows makes the scene even more melancholy. It looks as though the ship is still turning somewhat northward.

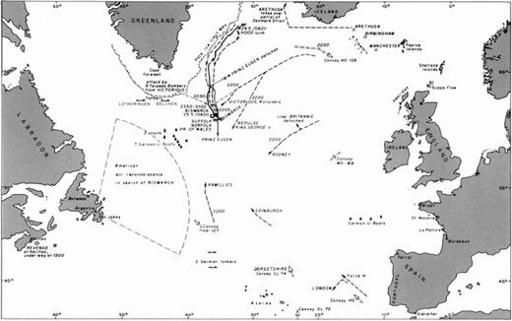

From 0600, German Summer Time, on 24 May to 0400, German Summer Time, on 25 May. Movements of the opposing forces between the battle off Iceland and the loss of contact with the Bismarck early on 25 May. (Diagram courtesy of Jürgen Rohwer.)

In the fire of his after turrets, we see clearly again the outline of the mighty ship, the long hull, the tower mast and stack, which now look like one solid, sturdy building, the after mast, at the top of which the Fleet Commander’s flag must be waving. Yet, because the distance between the two ships is rapidly increasing, it can no longer be made out. On the gaff below, waves the battle ensign, still recognizable as a dot.

Then the curtain of rain squalls closes for the last time. The “big brother” disappears from the sight of the many eyes following him from the

Prinz

, with great anxiety and the very best of wishes. According to orders, which could still be transmitted by signal light, the

Prinz Eugen

reduces speed. We are to act as a decoy, proceeding on the same course as before at a somewhat lower speed, in order to help the Bismarck, whose speed has been impaired, to escape from the British shadowers.

We in the

Bismarck

also had heavy hearts as we parted with the faithful

Prinz.

Only reluctantly did we leave her to her own destiny. In retrospect, it must be considered fortunate that we did, for against the concentration of heavy British ships that we later encountered we could not have been of much help to one another. Had we not separated, we probably would have lost the

Prinz Eugen

as well as the

Bismarck

on 27 May. As it was, she was able to reach the port of Brest undamaged on 1 June.

*

Lütjens’s radio signal of 0632, reporting the action, had not yet reached Group North; the repeat sent at 0705 never did get there.

|

The

Bismarck’s

gunfire, to which Schmalenbach refers, was being directed at our persistent shadower, the

Suffolk.

We met her in the course of our turn, and opened fire at a range of 18,000 meters. She immediately turned away and laid down smoke, but the

Prince of Wales

, which was farther away from us, opened up with her 356-millimeter guns. We turned to our originally planned southerly course and continued the gunnery duel with the

Prince of Wales.

But the extreme range at which we fought, 28,000 meters, coupled with the glare of the sun on the surface of the water and the clouds of stack smoke, made observation from the main fire-control center in the foretop so difficult that Schneider was able to fire only single salvos at long intervals. Since the enemy was astern of us, he eventually ordered me to take over the fire control. Apparently he thought that I, in my station aft, could see better. Such was not the case. The range was too great for me to make reliable observations, either. I told Schneider this, and after a few salvos had been fired at my direction we got the order to cease fire. Neither side scored a hit in this sporadic exchange of salvos. At 1914 Lütjens, still under a misapprehension about the identity of the British battleship, reported to the Seekriegsleitung, “Short action with

King George V

without result.

Prinz Eugen

released to fuel. Enemy maintains contact.”

Since leaving the

Prinz Eugen

, the fact that we were alone gradually sank into our consciousness and there was mounting tension as we wondered what surprises the coming hours and days might bring us. Something, we did not even have to wonder about. If for no other

reason than to make up for the shame of losing the

Hood

, the British would do everything they possibly could to bring an overwhelming concentration of powerful ships to bear on us. How many and which would they be? Where were they at the moment and in what combination? These uncertainties created tension and were the most important objects of our speculation. A great deal, if not everything, would depend on our shaking off our shadowers and getting as far as possible along the projected great curve towards western France without being observed. Our fuel supply being tight because of the 1,000 tons cut off in the forecastle, we reduced speed to an economical 21 knots. With a little luck, we would reach St. Nazaire without having to fight.

Shortly before 1900 Lütjens received Group West’s answer to the radio signal he had sent early that morning saying that he intended to take the

Bismarck

to St. Nazaire and to release the

Prinz Eugen

to conduct cruiser warfare. Group West concurred and had already made arrangements for the

Bismarck

to be received at St. Nazaire and also at Brest. The auxiliary arrangements at Brest had been made in case it became impossible for any reason for the

Bismarck

to go in to St. Nazaire.

Group West made the suggestion that, in the event enemy contact had been shaken off, the

Bismarck

make a long detour en route to port, obviously hoping that this would wear out the British pursuers. It was not a bad idea, and it is more than likely that Lütjens had considered doing just that. What Group West did not know was that the

Bismarck’s

fuel situation had been changed by the damage she had suffered—a fact that had not been reported. Therefore it must have been surprised to receive Lütjens’s radio signal of 2056: “Shaking off contact impossible due to enemy radar. Due to fuel steering direct for St. Nazaire.”

Why Lütjens considered our fuel situation so much more serious on the evening of 24 May than he had at midday, I do not know. Perhaps he had finally accepted the fact that there was no way we could draw on the fuel oil stored in the forecastle.

The Fleet Commander’s decision to make “direct for St. Nazaire” had immediate and important results. The Commander in Chief, U-Boats, supposing his instructions to form a line of U-boats south of Greenland to be thereby canceled, adjusted his dispositions to the

Bismarck’s

new course towards France. Appropriate instructions were sent to the

U-93, U-43, U-46, U-557, U-66

, and

U-94.

The

U-556

was ordered to act as a scout.

|

Since the fruitless action with the

Prince of Wales

, which took place a little after 1900 on 24 May, the

Bismarck

had held steady on her southerly course. Before long a report came over the ship’s loudspeakers that there was probably an aircraft carrier in the area. All our antiaircraft gun crews immediately went on full alert.

Then, around 2330—it was still light as day

*

—several pairs of aircraft were seen approaching on the port bow. They were beneath a layer of clouds and we could see them clearly, getting into formation to attack us. Naturally, we did not know it then, but they were from the

Victorious

, the carrier that accompanied Tovey’s force out of Scapa Flow on the evening of 22 May. Tovey’s objective was to intercept the German task force southwest of Iceland, in the unlikely event that, after Admiral Holland’s attack with the

Hood

and

Prince of Wales

, interception would still be necessary. It was.

Aircraft alarm! In seconds every antiaircraft gun on the

Bismarck

was ready for action. One after the other, the planes came towards us, nine Swordfish, torpedoes under their fuselages. Daringly they flew

through our fire, nearer to the fire-spitting mountain of the

Bismarck

, always nearer and still nearer. Watching through my director, which, having been designed for surface targets, had a high degree of magnification but only a narrow field, I could not see all the action. I could see only parts of it, and that only so far as the swirling smoke of our guns allowed. But what I could see was exciting enough.

Our antiaircraft batteries fired anything that would fit into their barrels. Now and again one of our 38-centimeter turrets and frequently our 15-centimeter turrets fired into the water ahead of the aircraft, raising massive waterspouts. To fly into one of those spouts would mean the end. And the aircraft: they were moving so slowly that they seemed to be standing still in the air, and they looked so antiquated. Incredible how the pilots pressed their attack with suicidal courage, as if they did not expect ever again to see a carrier.

In the meanwhile, we had increased speed to 27 knots and begun to zigzag sharply to avoid the torpedoes that were splashing into the water. This was an almost impossible task because of the close range and the low altitude from which the torpedoes were launched. Nevertheless, the captain and the quartermaster, Matrosenhauptgefreiter

*

Hans Hansen, who was steering from the open bridge, did a brilliant job. Some of the planes were only 2 meters above the water and did not release their torpedoes until they had closed to 400 or 500 meters. It looked to me as though many of them intended to fly on over us after making their attack. The height of impudence, I thought.