B0041VYHGW EBOK (99 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

6.48 … and slides down in a shower of exploding lights.

6.49 Cut to a new angle: Jackie leaps again, leading to an instant replay of the risky stunt.

Graphics, rhythm, space, and time, then, are at the service of the filmmaker through the technique of editing. They offer potentially unlimited creative possibilities. Yet most films we see make use of a very narrow set of editing possibilities—so narrow, indeed, that we can speak of a dominant editing style throughout film history. This is what is usually called

continuity editing

. Still, the most familiar way to edit a film isn’t the only way to edit a film, and so we’ll also consider some alternatives to continuity editing.

Around 1900–1910, as filmmakers started to use editing, they sought to arrange their shots so as to tell a story coherently and clearly. Thus editing, supported by specific strategies of cinematography and mise-en-scene, was used to ensure

narrative continuity.

So powerful is this style that, even today, anyone working in narrative filmmaking around the world is expected to be familiar with it.

As its name implies, the basic purpose of the continuity system is to allow space, time, and action to flow over a series of shots. All of the possibilities of editing we have already examined are turned to this end. First, graphic qualities are usually kept roughly continuous from shot to shot. The figures are balanced and symmetrically deployed in the frame; the overall lighting tonality remains constant; the action occupies the central zone of the screen.

Second, the rhythm of the cutting is usually made dependent on the camera distance of the shot. Long shots are left on the screen longer than medium shots, and medium shots are left on longer than close-ups. The assumption is that the spectator needs more time to take in the shots containing more details. In scenes of physical action like the fire in

The Birds,

accelerated editing rhythms may be present, but in general, shorter shots will tend to be closer views.

Since the continuity style seeks to present a story, it’s chiefly through the handling of space and time that editing furthers narrative continuity.

In the continuity style, the space of a scene is constructed along what is called variously the

axis of action

, the

center line,

or the

180° line.

The scene’s action—a person walking, two people conversing, a car racing along a road—is assumed to take place along a clear-cut vector. This axis of action determines a half-circle, or 180° area, where the camera can be placed to present the action. Consequently, the filmmaker will plan, film, and edit the shots so as to respect this center line. The camera work and mise-en-scene in each shot will be manipulated to establish and reiterate the 180° space.

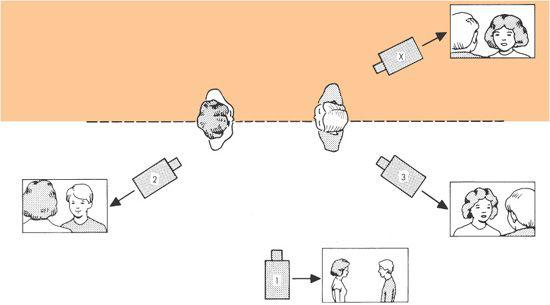

Consider the bird’s-eye view in

6.50

. We have a girl and a boy conversing. The axis of action is the imaginary line connecting the two people. Under the continuity system, the director would arrange the mise-en-scene and camera placement so as to establish and sustain this line. The camera can be put at any point as long as it stays on the same

side

of the line (hence the 180° term). A typical series of shots for coverage of the scene would be these: (1) a medium shot of the girl and boy, (2) a shot over the girl’s shoulder, favoring the boy, and (3) a shot over the boy’s shoulder, favoring the girl. But to cut to a shot from camera position X, or from any position within the tinted area, would be considered a violation of the system because it

crosses

the axis of action. Indeed, some handbooks of film directing call shot X flatly wrong. To see why, we need to examine what happens if a filmmaker follows the

180° system

.

6.50 A conversation scene and the axis of action.

The 180° system ensures that relative positions in the frame remain consistent.

In the shots taken from camera positions 1, 2, and 3, the characters occupy the same areas of the frame relative to each other. Even though we see them from different angles, the girl is always on the left and the boy is always on the right. But if we cut to shot X, the characters will switch positions in the frame. An advocate of traditional continuity would claim that shot X confuses us: Have the two characters somehow swiveled around each other?

The 180° system ensures consistent eyelines.

In shots 1, 2, and 3, the girl is looking right and the boy is looking left. Shot X violates this pattern by making the girl look to the left.

The 180° system ensures consistent screen direction.

Imagine now that the girl is walking left to right; her path constitutes the axis of action. As long as our shots do not cross this axis, cutting them together will keep the

screen direction

of the girl’s movement constant, from left to right. But if we

cross

the axis and film a shot from the other side, the girl will now appear on the screen as moving from

right to left.

Such a cut could be disorienting.

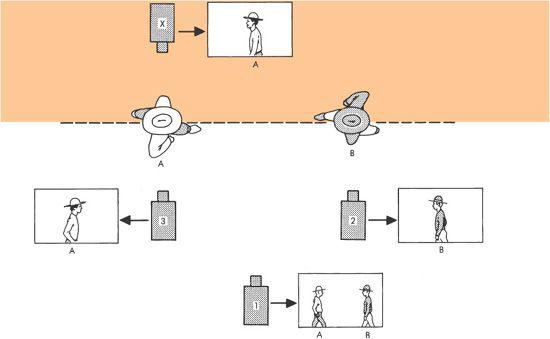

Consider a similar situation to that in

6.50

, a standard scene of two cowboys meeting for a shootout on a town street

(

6.51

).

Cowboy A and cowboy B form the 180° line, but here A is walking from left to right and B is approaching from right to left, both seen in the shot taken from camera position 1. A closer view, from camera position 2, shows B still moving from right to left. A third shot, from camera position 3, shows A walking, as he had been in the first shot, from left to right.

6.51 A Western shootout and the axis of action.

“… what I call ‘new brutalism’ in cinema … is a form of naïveté, because it’s made by people who I think don’t really have a grasp of cinema’s history. It’s the MTV kind of editing, where the main idea is that the more disorienting it is, the more exciting. And you see it creeping into mainstream cinema more and more. You look at something like

Armageddon

and you see all the things that would have been forbidden in classical cinema, like crossing the line, camera jumping from side to side. It is a way to artificially generate excitement, but it doesn’t really have any basis to it. And I find it kind of sad, because it’s like an old man trying to dress like a teenager.”— John Boorman, director

But imagine that this third shot was instead taken from position X, on the opposite side of the line. A is now seen as moving from right to left. Has he taken fright and turned around while the second shot, of B, was on the screen? The filmmakers may want us to think that he is still walking toward his adversary, but the change in screen directions could make us think just the opposite. A cut to a shot taken from any point in the colored area would create this change in direction. Such breaks in continuity can be confusing.

Even more disorienting would be crossing the line while establishing the scene’s action. In our shootout, if the first shot shows A walking from left to right and the second shot shows B (from the other side of the line) also walking left to right, we would probably not be sure that they were walking toward each other. The two cowboys would seem to be walking in the same direction at different points on the street, as if one were following the other. We would very likely be startled if they suddenly came face to face within the same shot.

The 180° system prides itself on delineating space clearly. The viewer should always know

where the characters are

in relation to one another and to the setting. More important, the viewer always knows

where he or she is

with respect to the story action. The space of the scene, clearly and unambiguously unfolded, does not jar or disorient, because such disorientation, it is felt, will distract the viewer from the center of attention: the narrative chain of causes and effects.

The Maltese Falcon

We saw in

Chapter 3

that the classical Hollywood mode of narrative subordinates time, motivation, and other factors to the cause–effect sequence. We also saw how mise-en-scene and camera work may present narrative material. Now we can note how, on the basis of the 180° principle, filmmakers have developed the continuity system as a way to build up a smoothly flowing space that remains subordinate to narrative action. Let’s consider a concrete example: the opening of John Huston’s film

The Maltese Falcon.

The scene begins in the office of detective Sam Spade. In the first two shots, this space is established in several ways. First, there is the office window (shot 1a,

6.52

), from which the camera tilts down to reveal Spade (shot 1b,

6.53

) rolling a cigarette. As Spade says, “Yes, sweetheart?” shot 2

(

6.54

)

appears. This is important in several respects. It is an

establishing shot

, delineating the overall space of the office: the door, the intervening area, the desk, and Spade’s position. Note also that shot 2 establishes a 180° line between Spade and his secretary, Effie; Effie could be the girl in

6.50

, and Spade could be the boy. The first phase of this scene will be built around staying on the same side of this 180° line.

6.52

The Maltese Falcon:

shot 1a.