B0041VYHGW EBOK (97 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

Editing usually serves not only to control graphics and rhythm but also to construct film space. Exhilaration in this newly discovered power can be sensed in the writings of such filmmakers as the Soviet director Dziga Vertov: “I am Kino-eye. I am builder. I have placed you … in an extraordinary room which did not exist until just now when I also created it. In this room there are twelve walls, shot by me in various parts of the world. In bringing together shots of walls and details, I’ve managed to arrange them in an order that is pleasing.”

Such elation is understandable. Editing permits the filmmaker to juxtapose

any

two points in space and thus imply some kind of relationship between them.

The director might, for instance, start with a shot that establishes a spatial whole and follow this with a shot of a part of this space. This is what Hitchcock does in shot 1 and shot 2 of the

Birds

sequence (

6.5

,

6.6

): a medium long shot of the group of people followed by a medium shot of only one, Melanie. Such analytical breakdown is a very common editing pattern.

Alternatively, the filmmaker could construct a whole space out of component parts. Hitchcock does this later in the

Birds

sequence. Note that in

6.5

–

6.8

and in shots 30–39 (

6.23

–

6.32

), we do not see an establishing shot including Melanie

and

the gas station. In production, the restaurant window need not have been across from the station at all; they could have been filmed in different towns or even countries. Yet we are compelled to believe that Melanie is across the street from the gas station. The bird cry offscreen and the mise-en-scene (the window and Melanie’s sideways glance) contribute considerably as well. Still, the editing plays a major role in creating the spatial whole of restaurant-and-gas-station.

Such spatial manipulation through cutting is fairly common. In documentaries compiled from newsreel footage, for example, one shot might show a cannon firing, and another shot might show a shell hitting its target; we infer that the cannon fired the shell, though the shots may show entirely different battles. Again, if a shot of a speaker is followed by a shot of a cheering crowd, we assume a spatial coexistence.

The possibility of such spatial manipulation was examined by the Soviet filmmaker Lev Kuleshov. During the 1920s, Kuleshov conducted informal experiments by assembling shots of separate dramatic elements. The most famous of these experiments involved cutting neutral shots of an actor’s face with other shots (variously reported as shots of soup, nature scenes, a dead woman, and a baby). The reported result was that the audience immediately assumed that the actor’s expression changed and that the actor was reacting to things present in the same space as himself. Similarly, Kuleshov cut together shots of actors “looking at each other” but on Moscow streets miles apart, then meeting and strolling together—and looking at the White House in Washington. Although filmmakers had used such cutting before Kuleshov’s work, film scholars call the

Kuleshov effect

any series of shots that

in the absence of an establishing shot

prompts the spectator to infer a spatial whole on the basis of seeing only portions of the space.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

For more on why the Kuleshov effect works so well and on how it has been used in some older and more recent films, see “What happens between shots happens between your ears,” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=1861

.

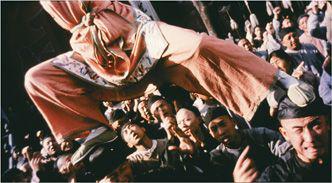

The Kuleshov effect can conjure up robust cinematic illusions. In Corey Yuen’s

Legend of Fong Sai-Yuk,

a martial-arts bout between the hero and an adept woman begins on a platform but then moves into the audience—or rather, onto the audience. The two fight while balancing on the heads and shoulders of the crowd. Yuen’s rapid editing conveys the scene’s point by means of the Kuleshov effect

(

6.34

,

6.35

).

(In production, this meant that the combatants could be hung on wires or bars suspended outside the frame, as in

6.35

.) Across many shots, Yuen provides only a few brief full-figure framings showing Fong Sai-Yuk and the woman.

6.34 In

The Legend of Fong Sai-Yuk,

a shot of the woman’s upper body is followed by …

6.35 … a shot of her legs and feet, supported by unwilling bystanders.

“Editing is very interesting and absorbing work because of the illusions you can create. You can span thirty years within an hour and a half. You can stretch a moment in slow motion. You can play with time in extraordinary ways.”

— Paul Hirsch, editor

While the viewer doesn’t normally notice the Kuleshov effect, a few films call attention to it. Carl Reiner’s

Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid

mixes footage filmed in the present with footage from Hollywood movies of the 1940s. Thanks to the Kuleshov effect,

Dead Men

creates unified scenes in which Steve Martin converses with characters who were originally featured in other films. In

A Movie,

Bruce Conner makes a joke of the Kuleshov effect by cutting from a submarine captain peering through a periscope to a woman gazing at the camera, as if they could see each other

(

6.36

,

6.37

).

6.36 In

A Movie,

a shot from one film leads to …

6.37 … a shot from another, creating a visual joke.

In the Kuleshov effect, editing cues the spectator to infer a single locale. Editing can also emphasize action taking place in separate places. In

Intolerance,

D. W. Griffith cuts from ancient Babylon to Gethsemane and from France in 1572 to America in 1916. Such parallel editing, or

crosscutting

, is a common way films construct a variety of spaces.

More radically, the editing can present spatial relations as being ambiguous and uncertain. In Carl Dreyer’s

La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc,

for instance, we know only that Jeanne and the priests are in the same room. Because the neutral white backgrounds and the numerous close-ups provide no orientation to the entire space, we can seldom tell how far apart the characters are or precisely who is beside whom. We’ll see later how films can create even more extreme spatial discontinuities.

Like other film techniques, editing can control the time of the action denoted in the film. In a narrative film especially, editing usually contributes to the plot’s manipulation of story time. You will recall that

Chapter 3

pointed out three areas in which plot time can cue the spectator to construct the story time: order, duration, and frequency. Our

Birds

example (

6.5

–

6.8

) shows how editing reinforces all three areas of control.

First, there is the

order

of presentation of events. The men talk, then Melanie turns away, then she sees the gull swoop, then she responds. Hitchcock’s editing presents these story events in the 1-2-3-4 order of his shots. But he could have shuffled the shots into any order at all, even reverse (4-3-2-1). This is to say that the filmmaker may control temporal succession through the editing.

Such manipulation of events leads to changes in story–plot relations. We are most familiar with such manipulations in

flashbacks

, which present one or more shots out of their presumed story order. In

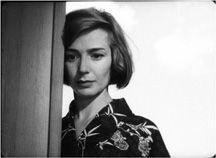

Hiroshima mon amour,

Resnais uses the protagonist’s memory to motivate a violation of temporal order. Three shots

(

6.38

–

6.40

)

suggest visually that the position of her current lover’s hand triggers a recollection of another lover’s death years before. In contemporary cinema, brief flashbacks to key events may brutally interrupt present-time action.

The Fugitive

uses this technique to return obsessively to the murder of Dr. Kimball’s wife, the event that initiated the story’s action.

6.38 In

Hiroshima mon amour,

a view of the protagonist’s Japanese lover asleep is followed by …

6.39 … a shot of her looking at him, leading to …