B0041VYHGW EBOK (103 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

6.80

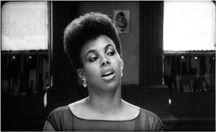

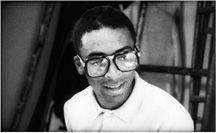

She’s Gotta Have It.

6.81

She’s Gotta Have It.

Through eyelines and body orientations, Lee’s editing keeps the spatial relations completely consistent. For example, each man looks in a different direction when addressing Nola

(

6.82

,

6.83

).

This cutting pattern enhances the dramatic action by making all the men equal competitors for her. They are clustered at one end of the table, and none is shown in the same frame with her. In addition, by organizing the angles around her overall orientation to the action (as in

6.84

, an optical point-of-view shot), Lee keeps Nola the pivotal character. Further, the longer shot and her separate medium close-ups intensify the progression of the scene: the men are on display, and Nola is coolly judging each one’s behavior.

6.82

She’s Gotta Have It.

6.83

She’s Gotta Have It.

6.84

She’s Gotta Have It.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

Another refinement: What happens if the reverse shot is withheld? We show some examples and discuss their functions in “Angles and perceptions.”

Another felicity in the 180° system is the

cheat cut

. Sometimes a director may not have perfect continuity from shot to shot because he or she has composed each shot for specific reasons. Must the two shots match perfectly? Again, narrative motivation decides the matter. Given that the 180° system emphasizes story action, if we’re paying attention to that, the director has some freedom to “cheat” mise-en-scene from shot to shot—that is, to mismatch slightly the positions of characters or objects.

Consider two shots from William Wyler’s

Jezebel.

Neither character moves during either shot, but Wyler has blatantly cheated the position of Julie

(

6.85

,

6.86

).

Yet most viewers would not notice the discrepancy since it’s the dialogue that is paramount in the scene; here again, the similarities between shots outweigh the differences of position. Moreover, a change from a straight-on angle to a slightly high angle helps hide the cheat. There is, in fact, a cheat in the

Maltese Falcon

scene, too, between shots 6b and 7. In 6b (

6.60

), as Spade leans forward, the back of his chair is not near him. Yet in shot 7 (

6.61

), it has been cheated to be just behind his left arm. Here again, the primacy of the narrative flow overrides such a cheat cut.

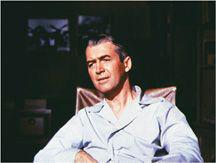

6.85 In this shot from

Jezebel,

the top of Julie’s head is even with the man’s chin …

6.86 … but in the second shot she seems to have grown several inches.

One more fine point in spatial continuity is particularly relevant to a film’s narration. We have already seen that a camera framing can strongly suggest a character’s optical point of view, rendering the narration subjective. We see this in our earlier example from

Fury

(

5.112

,

5.113

). That example depends on a cut from the person looking (

5.112

) to what he sees (

5.113

). We have also seen an instance of POV cutting in the

Birds

sequence discussed on

pp. 228

–231. Now we are in a position to see how optical POV is consistent with continuity editing, creating a variety of eyeline-match editing known as

point-of-view cutting.

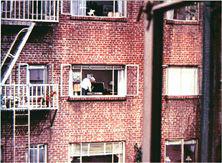

Alfred Hitchcock’s

Rear Window

is built around the situation of the solitary photographer Jeff watching events taking place in an apartment across the courtyard. Hitchcock uses a standard eyeline-match pattern, cutting from a shot of Jeff looking

(

6.87

)

to a shot of what he sees

(

6.88

).

Since there is no establishing shot that shows both Jeff and the opposite apartment, the Kuleshov effect operates here: our mind connects the two images. More specifically, the second shot represents Jeff’s optical viewpoint, and this is filmed from a position on his end of the axis of action

(

6.89

).

The camera has not crossed the line. We are strongly restricted to what Jeff sees and what (he thinks) he knows.

6.87 In

Rear Window,

Jeff looks out his window and …

6.88 … the next shot shows what he sees from his optical POV.

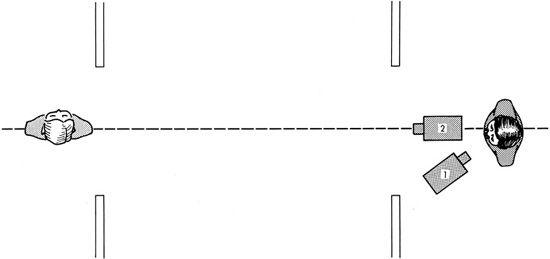

6.89 An overhead diagram of the

Rear Window

POV shot.