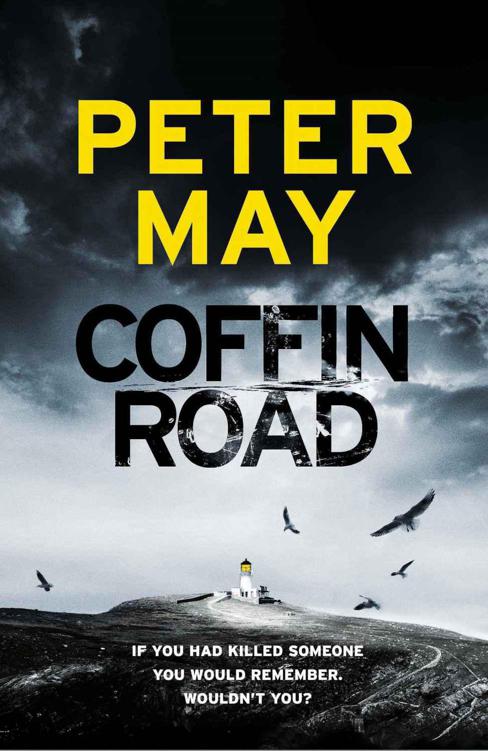

Coffin Road

Authors: Peter May

Coffin Road

Also By

Also by Peter May

FICTION

The Lewis Trilogy

The Blackhouse

The Lewis Man

The Chessmen

The China Thrillers

The Firemaker

The Fourth Sacrifice

The Killing Room

Snakehead

The Runner

Chinese Whispers

The Enzo Files

Extraordinary People

The Critic

Blacklight Blue

Freeze Frame

Blowback

Stand-alone Novels

Runaway

Entry Island

NON-FICTION

Hebrides

(with David Wilson)

Title

Copyright

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

Quercus Publishing Ltd

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

An Hachette UK company

Copyright © 2016 Peter May

The moral right of Peter May to be

identified as the author of this work has been

asserted in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication

may be reproduced or transmitted in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any

information storage and retrieval system,

without permission in writing from the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library.

HB ISBN 978 1 78429 312 3

TPB ISBN 978 1 78429 309 3

EBOOK ISBN 978 1 78429 308 6

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters,

businesses, organizations, places and events are

either the product of the author’s imagination

or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to

actual persons, living or dead, events or

locales is entirely coincidental.

Dedication

For the bees

Epigraph

‘

Scientists . . . submitting works on neonicotinoids

or the long-term effects of GMO crops, trigger

corporate complaints . . . and find that their

careers are in jeopardy.’

Jeff Ruch, Executive Director of PEER

(Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility)

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

The first thing I am aware of is the taste of salt. It fills my mouth. Invasive. Pervasive. It dominates my being, smothering all other senses. Until the cold takes me. Sweeps me up and cradles me in its arms. Holding me so tightly I can’t seem to move. Except for the shivering. A raging, uncontrollable shivering. And somewhere in my mind I know this is a good thing. My body trying to generate heat. If I wasn’t shivering I would be dead.

It seems an eternity before I am able to open my eyes, and then I am blinded by the light. A searing pain in my head, pupils contracting rapidly to bring a strange world into focus. I am lying face-down, wet sand on my lips, in my nostrils. Blinking furiously, making tears to wash the stuff from my eyes. And then it is all I can see. Sand, stretching away to a blurred horizon. Tightly ribbed. Platinum pale. Almost bleached.

And now I am aware of the wind. Tugging at my clothes, sending myriad grains of sand in a veil of whisper-thin gauze across the beach in currents and eddies, like water.

There is, it seems, almost no feeling in my body as I force myself to my knees, muscles moved by memory more than will. And almost immediately my stomach empties its contents on to the sand. The sea that has filled it, bitter and burning in my mouth and throat as it leaves me. My head hanging down between shoulders supported on shaking arms, and I see the bright orange of the life jacket that must have saved me.

Which is when I hear the sea for the first time, above the wind, distinguishing it from the rushing sound in my head, the God-awful tinnitus that drowns out almost everything else.

Heaven knows how, but I am up and standing now on jelly legs, my jeans and trainers, and my sweater beneath the life jacket, heavy with the sea, weighing me down. My lungs are trembling as I try to control my breathing, and I see the distant hills that surround me, beyond the beach and the dunes, purple and brown, grey rock bursting through the skin of thin, peaty soil that clings to their slopes.

Behind me the sea retreats, shallow, a deep greenish-blue, across yet more acres of sand towards the distant, dark shapes of mountains that rise into a bruised and brooding sky. A sky broken by splinters of sunlight that dazzle on the ocean and dapple the hills. Glimpses of sailor-suit blue seem startling and unreal.

I have no idea where this is. And for the first time since consciousness has returned, I am aware, with a sudden, sharp and painful stab of trepidation, that I have not the least notion of who I am.

That breathless realisation banishes all else. The cold, the taste of salt, the acid still burning all the way up from my stomach. How can I not know who I am? A temporary confusion, surely? But the longer I stand here, with the wind whistling around my ears, shivering almost beyond control, feeling the pain and the cold and the consternation, I realise that the only sense that has not returned to me is my sense of self. As if I inhabit the body of a stranger, in whose uncharted waters I have been washed up in blind ignorance.

And with that comes something dark. Neither memory nor recollection, but a consciousness of something so awful that I have no desire to remember it, even if I could. Something obscured by . . . what? Fear? Guilt? I force myself to refocus.

Away to my left I see a cottage, almost at the water’s edge. A stream, brown with peat, washes down from hills that lift beyond it, cutting a curving path through smooth sand. Headstones rise up from a manicured green slope, higgledy-piggledy behind barbed-wire fencing and a high stone wall. The ghosts of centuries watching from the silence of eternity as I stagger across the sand, feet sinking nearly ankle-deep in its softness. A long way off to my right, on the far shore, beside a caravan just above the beach, I see a figure standing in silhouette, sunlight spilling down from the hills beyond. Too far away to discern sex or size or form. Hands move up to a pale face, elbows raised on either side, and I realise that he or she has lifted binoculars to curious eyes and is watching me. For a moment I am tempted to shout for help, but know that, even had I the strength, my voice would be carried off by the wind.

So I focus instead on the path I see winding off through the dunes to the dark ribbon of metalled, single-track road that clings to the contour of the near shore as it snakes away beyond the headland.

It takes an enormous effort of will to wade through the sand and the spiky beach grass that binds the dunes, staggering up the narrow path that leads between them to the road. Momentarily sheltered from the constant, battering wind, I lift my head to see a woman coming along the road towards me.

She is elderly. Steel-grey hair blown back in waves from a bony face, skin stretched tight and shiny over bold features. She is wearing a parka, hood down, and black trousers that gather over pink trainers. A tiny yapping dog dances around her feet, little legs working hard to keep up, to match her longer strides.

When she sees me she stops suddenly, and I can see the shock on her face. And I panic, almost immediately overwhelmed by the fear of whatever it is that lies beyond the black veil of unremembered history. As she approaches, hurrying now, concerned, I wonder what I can possibly say to her when I have no sense of who or where I am, or how I got here. But she rescues me from the need to find words.

‘Oh my God, Mr Maclean, what on earth has happened to you?’

So that’s who I am. Maclean. She knows me. I am suffused by a momentary sense of relief. But nothing comes back. And I hear my own voice for the first time, thin and hoarse and almost inaudible, even to myself. ‘I had an accident with the boat.’ The words are no sooner out of my mouth than I find myself wondering if I even have a boat. But she shows no surprise.

She takes my arm to steer me along the road. ‘For heaven’s sake, man, you’ll catch your death. I’ll walk you to the cottage.’ Her yappy little dog nearly trips me up, running around between my feet, jumping at my legs. She shouts at it and it pays her not the least attention. I can hear her talking, words tumbling from her mouth, but I have lost concentration, and she might be speaking Russian for all that I understand.

We pass the gate to the cemetery, and from this slightly elevated position I have a view of the beach where the incoming tide dumped me. It is truly enormous, curling, shallow fingers of turquoise lying between silver banks that curve away to hills that undulate in cut-out silhouette to the south. The sky is more broken now, the light sharp and clear, clouds painted against blue in breathless brushstrokes of white and grey and pewter. Moving fast in the wind to cast racing shadows on the sand below.

Beyond the cemetery we stop at a strip of tarmac that descends between crooked fenceposts, across a cattle grid, to a single-storey cottage that stands proud among the dunes, looking out across the sands. A shaped and polished panel of wood, fixed between fenceposts, has

Dune Cottage

scorched into it in black letters.

‘Do you want me to come in with you?’ I hear her say.

‘No, I’m fine, thank you so much.’ But I know that I am far from fine. The cold is so deep inside me that I understand if I stop shivering I could fall into a sleep from which I might never wake. And I stagger off down the path, aware of her watching me as I go. I don’t look back. Beyond a tubular farm gate, a path leads away to an agricultural shed of some kind, and at the foot of the drive, a garden shed on a concrete base stands opposite the door of the cottage, which is set into its gable end.

A white Highland pony feeding on thin grass beyond the fence lifts its head and also watches, curious, as I fumble in wet pockets for my keys. If this is my cottage surely I must have keys for it? But I can’t find any, and try the handle. The door is not locked, and as it opens I am almost knocked from my feet by a chocolate Labrador, barking and snorting excitedly, eyes wide and smiling, paws up on my chest, tongue slashing at my face.

And then he is gone. Through the gate and haring away across the dunes. I call after him. ‘Bran! Bran!’ I hear my own voice, as if it belongs to someone else, and realise with a sudden stab of hope that I know my dog’s name. Perhaps the memory of everything else is just a whisper away.

Bran ignores my calls, and in moments is lost from sight. I wonder how many hours I have been away, and how long he has been shut up in the house. I glance back up the drive, to the tarmac turning area behind the house, and it occurs to me that there is no car, which seems odd in this remotest of places.

A wave of nausea sweeps over me and I am reminded again that I need to raise my core temperature fast, to get out of these clothes as quickly as possible.

I stumble into what seems to be a utility and boot room. There is a washing machine and tumble dryer beneath a window and worktop, a central-heating boiler humming softly beyond its casing. A wooden bench is pushed up against the wall on my left below a row of coats and jackets. There are walking boots and wellies underneath the bench, and dried mud on the floor. I kick off my shoes and rip away the life jacket before struggling unsteadily into the kitchen, supporting myself on the door jamb as I push through the open door.

It is the strangest feeling to enter a house that you know is your own, and yet find not one thing about it that is familiar. The row of worktops and kitchen cabinets on my left. The sink and hob. The microwave and electric oven. Opposite, below a window that gives on to a panoramic view of the beach, is the kitchen table. It is littered with newspapers and old mail. A laptop is open but asleep. Among these things, surely, I will find clues as to who I am. But there are more pressing matters.

I fill the kettle and turn it on, then pass through an archway into the sitting room. French windows open on to a wooden deck, with table and chairs. The view is breathtaking. A porthole window on the far wall looks out on to the cemetery. In the corner, a wood-burning stove. Two two-seater leather settees gather themselves around a glass coffee table. A door leads into a hall that runs the length of the cottage, along its spine. To the right, another door opens into a large bedroom. The bed is unmade and, as I stumble into the room, I see clothes piled up on a chair. Mine, I presume. Yet another door leads off to an en-suite shower room, and I know what I must do.

With fumbling fingers I manage to divest myself of my wet clothes, leaving them lying on the floor where they fall. And, with buckling legs, I haul myself into the shower room.

The water runs hot very quickly, and as I step under it I almost collapse from the warmth it sends cascading over my body. Arms stretched, palms flat against the tiles, I support myself and close my eyes, feeling weak, and just stand there with the water breaking over my head until I feel the heat of it very slowly start to seep into my soul.

I have no idea how long I remain there, but with warmth and an end to shivering comes the return of that same black cloud of apprehension which almost overcame me on the beach. A sense of something unspeakable beyond the reach of recollection. And with that the full, depressing realisation that I still have no grasp of who I am. Or, disconcertingly, even what I look like.

I step from the shower to rub myself briskly with a big, soft bath towel. The mirror above the sink is misted, and so I am just a pink blur when I stoop to peer into it. I slip on a towelling bathrobe that hangs on the door and pad back through to the bedroom. The house feels hot, airless. The floor, warm beneath my feet. And as that same warmth infuses my body, so I feel all its aches and pains. Muscles in arms, legs and torso that are stiff and sore. In the kitchen I search for coffee and find a jar of instant. I spoon it into a mug and pour in boiled water from the kettle. I see a jar of sugar, but have no idea if I take it in my coffee. I sip at the steaming black liquid, almost scalding my lips, and think not. It tastes just fine as it is.

With almost a sense of trepidation, I carry it back through to the bedroom and lay it on the dresser, to slip from my bathrobe and stand before the full-length mirror on the wardrobe door to look at the silvered reflection of the stranger staring back at me.

I cannot even begin to describe how dissociating it is to look at yourself without recognition. As if you belong somewhere outside of this alien body you inhabit. As if you have simply borrowed it, or it has borrowed you, and neither belongs to the other.

Nothing about my body is familiar. My hair is dark, and though not long, quite curly, falling wet in loops over my forehead. This man appraising me with his ice-blue eyes seems quite handsome, if it is possible for me to be at all objective. Slightly high cheekbones and a dimpled chin. My lips are pale but fairly full. I try to smile, but the grimace I make lacks any humour. It reveals good, strong, white teeth, and I wonder if I have been bleaching them. Would that make me vain? From somewhere, completely unexpectedly, comes the memory of someone I know drinking his coffee through a straw so as not to discolour brilliantly white teeth made porous by bleach. Or perhaps it is not someone I know, just something I have read somewhere, or seen in a movie.

I seem lean and fit, with only the hint of a paunch forming around my middle. My penis is flaccid and very small – shrunken, I hope, only by the cold. And I find myself smiling, this time for real. So I am vain. Or perhaps just insecure in my masculinity. How bizarre not to know yourself, to find yourself guessing at who you are. Not your name, or the way you look, but the essential you. Am I clever or stupid? Do I have a quick temper? Am I made easily jealous? Am I charitable or selfish? How can I not know these things?

And as for age . . . For God’s sake, what age am I? How hard it is to tell. I see the beginnings of grey at my temples, fine crow’s feet around my eyes. Mid-thirties? Forty?

I notice a scar on my left forearm. Not recent, but quite pronounced. Some old injury. An accident of some kind. There is a graze in my hairline, blood seeping slowly through black hair. And I see also, on my hands and forearms, several small, red, raised lumps with tiny scabs at their centre. Bites of some sort? But they don’t seem to hurt or itch.