B0041VYHGW EBOK (188 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

With this huge financial backing, UFA was able to gather superb technicians and build the best-equipped studios in Europe. These studios later attracted foreign filmmakers, including the young Alfred Hitchcock. During the 1920s, Germany coproduced many films with companies in other countries, thus helping to spread German stylistic influence abroad.

In late 1918, with the end of the war, the need for overt militarist propaganda disappeared. Although mainstream dramas and comedies continued to be made, the German film industry concentrated on three genres. One was the internationally popular adventure serial, featuring spy rings, clever detectives, or exotic settings. Another was a brief sex exploitation cycle, which dealt “educationally” with such topics as homosexuality and prostitution. Also, UFA set out to copy the popular Italian historical epics of the prewar period.

This last type of film proved financially successful. In spite of continued bans on and prejudice against German films in America, England, and France, UFA finally was able to break into the international market. In September 1919, Ernst Lubitsch’s

Madame Dubarry,

an epic of the French Revolution

(

12.18

),

inaugurated the magnificent UFA Palast theater in Berlin. This film helped reopen the world film market to Germany. Released as

Passion

in the United States, this film was extremely popular. It was not enthusiastically received in France, where its premiere was considerably delayed by charges that it was anti-French propaganda. But it did well in most markets, and other Lubitsch historical films were soon exported. In 1923, he became the first German director to be hired by Hollywood.

12.18

Madame Dubarry:

a crowd scene in the Tribunal of the French Revolution.

Some small companies briefly remained independent. Among these was Erich Pommer’s Decla (later Decla-Bioscop). In 1919, the firm undertook to produce an unconventional script by two unknowns, Carl Mayer and Hans Janowitz. These young writers wanted

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

to be made in an unusually stylized way. The three designers assigned to the film—Hermann Warm, Walter Reimann, and Walter Röhrig—suggested that it be done in an Expressionist style. As an avant-garde movement, Expressionism had first been important in painting (starting about 1910) and had been quickly taken up in theater, then in literature and architecture. Now company officials consented to try it in the cinema, apparently believing that this might be a selling point in the international market.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

For a discussion of the restoration of another historical epic by Lubitsch,

Das Weib des Pharao,

see “Preserving two masters,” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=3116

.

This belief was vindicated in 1920 when Decla’s inexpensive film

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

(1920) created a sensation in Berlin and then in the United States, France, and other countries. Because of its success, other films in the Expressionist style soon followed. The result was a stylistic movement in cinema that lasted several years.

“Everything is composition; any image whatsoever could be stopped on the screen and would be a marvellously balanced painting of forms and lights. Also, it is one of the films which leaves in our memories the clearest visions—precise and of a slightly static beauty. But even more than painting, it is animated architecture.”

— François Berge, French critic, on Fritz Lang’s

The Nibelungen

The success of

Caligari

and other Expressionist films kept Germany’s avantgarde directors largely within the industry. A few experimental filmmakers made abstract films, like Viking Eggeling’s

Diagonal-symphonie

(1923), or Dada films influenced by the international art movement, like Hans Richter’s

Ghosts Before Breakfast

(1928). Big firms such as UFA (which absorbed Decla-Bioscop in 1921), as well as smaller companies, invested in Expressionist films because these films could compete with those of America. Indeed, by the mid-1920s, the most prominent German films were widely regarded as among the best in the world.

The first film of the movement,

Caligari,

is also one of the most typical examples. One of its designers, Warm, claimed, “The film image must become graphic art.”

Caligari,

with its extreme stylization, was indeed like a moving Expressionist painting or woodcut print. In contrast to French Impressionism, which bases its style primarily on cinematography and editing, German Expressionism depends heavily on mise-en-scene. Shapes are distorted and exaggerated unrealistically for expressive purposes (4.2). Actors often wear heavy makeup and move in jerky or slow, sinuous patterns. Most important, all of the elements of the mise-en-scene interact graphically to create an overall composition. Characters do not simply exist within a setting but rather form visual elements that merge with the setting

(

12.19

).

We have already seen an example of this in 4.105, where the character Cesare collapses in a stylized forest, his body and outstretched arms echoing the shapes of the trees’ trunks and branches.

12.19 The heroine’s flamboyantly Expressionistic bedroom in Robert Wiene’s

Genuine.

As she leans backwards, she blends with the curved, spiky shapes behind her.

In

Caligari,

the Expressionist stylization functions to convey the distorted viewpoint of a madman. We see the world as the hero imagines it to be. This narrative function of the settings becomes explicit at one point, when the hero enters an asylum in his pursuit of Caligari. As he pauses to look around, he stands at the center of a pattern of radiating black-and-white lines that run across the floor and up the walls

(

12.20

).

The world of the film is literally a projection of the hero’s vision.

12.20 The insane asylum set of

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

Later, as Expressionism became an accepted style, filmmakers didn’t motivate Expressionist style as the narrative point of view of mad characters. Instead, Expressionism often functioned to create stylized situations for fantasy and horror stories (as with

Waxworks,

1924, and

Nosferatu,

1922; see 9.16) or historical epics (as with

The Nibelungen,

1923–1924). Expressionist films depended greatly on their designers. In the German studios, a film’s designer received a relatively high salary and was often mentioned prominently in the advertisements.

A combination of circumstances led to the disappearance of the movement. The rampant inflation of the early 1920s in Germany actually favored Expressionist filmmaking, partly by making it easy for German exporters to sell their films cheaply abroad. Inflation discouraged imports, however, for the tumbling exchange rate of the mark made foreign purchases prohibitively expensive. But in 1924, the U.S. Dawes Plan helped to stabilize the German economy, and foreign films came in more frequently, offering a degree of competition unknown in Germany for nearly a decade. Expressionist film budgets, however, were climbing. The last major films of the movement, F. W. Murnau’s

Faust

(1926) and Fritz Lang’s

Metropolis

(1927), were costly epics that helped drive UFA deeper into financial difficulty, leading Erich Pommer to quit and try his luck briefly in America

(

12.21

).

Other personnel were lured away to Hollywood as well. Murnau left after finishing

Faust,

his last German film. Major actors (such as Conrad Veidt and Emil Jannings) and cinematographers (such as Karl Freund) went to Hollywood as well. Lang stayed on, but after the criticisms of

Metropolis

’s extravagance on its release, he formed his own production company and turned to other styles in his later German films. At the beginning of the Nazi regime in 1933, he too left the country.

12.21

Metropolis

contained many large, Expressionistic sets, including this garden, with pillars that appear to be made of meltingclay.

Trying to counter the stiffer competition from imported Hollywood films after 1924, the Germans also began to imitate the American product. The resulting films, though sometimes impressive, diluted the unique qualities of the Expressionist style. Thus, by 1927, Expressionism as a movement had died out. But as Georges Sadoul has pointed out, an expressionist (spelled with a lowercase “e” to distinguish it from the Expressionist movement proper) tendency lingered on in many of the German films of the late 1920s and even into such 1930s films as Lang’s

M

(1930; see

12.22

) and

Testament of Dr. Mabuse

(1932). And because many of the German filmmakers came to the United States, Hollywood horror films also displayed film noir’s expressionist tendencies in their settings and lighting. Although the German movement lasted only about seven years, expressionism has never entirely died out as a trend in film style.

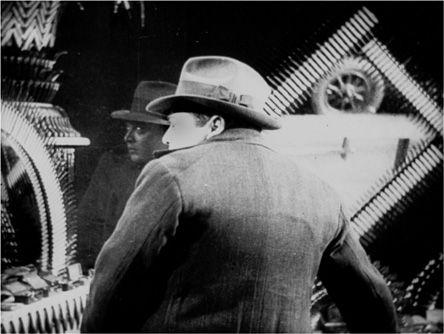

12.22 In

M,

reflections and a display of knives in a shop window create a semi-abstract composition that mirrors the murderer’s obsession.