B0041VYHGW EBOK (186 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

Edison was determined to exploit the money-making potential of his company’s invention. He tried to force competing filmmakers out of business by bringing patent-violation suits against them. One other company, American Mutoscope & Biograph, managed to survive by inventing cameras that differed from Edison’s patents. Other firms kept operating while Edison fought them in court. In 1908, Edison cooperated with Biograph to bring these other companies under control by forming the Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPC), a group of 10 firms based primarily in Chicago, New York, and New Jersey. Edison and Biograph were the only stockholders and patent owners. They licensed other members to make, distribute, and exhibit films.

The MPPC never succeeded in eliminating its competition. Numerous independent companies were established throughout this period. Biograph’s most important director from 1908 on, D. W. Griffith, formed his own company in 1913, as did other filmmakers. The United States government brought suit against the MPPC in 1912; in 1915, it was declared a monopoly.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

Hollywood wasn’t the only place where film form and style were developing in the 1910s. For an international survey of the important year 1913, see “Lucky ’13,” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=2674

.

Around 1910, film companies began to move permanently to California. Some historians claim that the independent companies fled west to avoid the harassment of the MPPC, but some MPPC companies also made the move. Among the advantages of Hollywood were the climate, which permitted shooting year-round, and the great variety of terrains—mountains, ocean, desert, city—available for location shooting. Soon Hollywood and other small towns on the outskirts of Los Angeles played host to film production.

The demand for films was so great that no single studio could meet it. This was one of the factors that had led Edison to accept the existence of a group of other companies, although he tried to control them through his licensing procedure. Before 1920, the American industry assumed the structure that would continue for decades: a few large studios with individual artists under contract and a peripheral group of small, independent producers. In Hollywood, the studios developed a factory system, with each production under the control of the producer, who usually did not work on the actual making of the films. Even an independent director such as Buster Keaton, with his own studio, distributed his films through larger companies, first Metro and then United Artists.

“The cinema knows so well how to tell a story that perhaps there is an impression that it has always known how.”

— André Gaudreault, film historian

Gradually, through the 1910s and 1920s, the smaller studios merged to form the large firms that still exist today. Famous Players joined with Jesse L. Lasky and then formed a distribution wing, Paramount. By the late 1920s, most of the major companies—MGM (a merger of Metro, Goldwyn, and Mayer), Fox Film Corporation (merged with 20th Century in 1935), Warner Bros., Universal, and Paramount—had been created. Though in competition with one another, these studios tended to cooperate to a degree, realizing that no one firm could satisfy the market.

Within this system of mass-production studios, the American cinema became definitively oriented toward narrative form. Early films had consisted primarily of tableaux or vaudeville skits (

12.5

). One of Edison’s directors, Edwin S. Porter, made some of the first films to use principles of narrative continuity and development. Among these was

The Life of an American Fireman

(1903), which showed the race of the firefighters to rescue a mother and a child from a burning house. Although this film used several important classical narrative elements (a fireman’s premonition of the disaster, a series of shots of the horse-drawn engine racing to the house), it still had not worked out the logic of temporal relations in cutting. Thus we see the rescue of a mother and her child twice, from both inside and outside the house. Porter had not realized the possibility of intercutting the two locales within the action or matching on action to convey narrative information to the audience.

In 1903, Porter made

The Great Train Robbery,

in some ways a prototype for the classical American film. Here the action develops with a clear linearity of time, space, and logic. We follow each stage of the robbery

(

12.6

),

the pursuit, and the final defeat of the robbers. In 1905, Porter also created a simple parallel narrative in

The Kleptomaniac,

contrasting the fates of a rich woman and a starving woman who are both caught stealing.

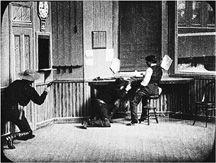

12.6 The robbers in the telegraph office in

The Great Train Robbery,

preparing to board the train seen through the window.

British filmmakers were working along similar lines. Indeed, many historians now believe that Porter derived some of his editing techniques from films such as James Williamson’s

Fire!

(1901) and G. A. Smith’s

Mary Jane’s Mishap

(1903). The most famous British film of this era was Lewin Fitzhamon’s 1905 film

Rescued by Rover

(produced by a major British firm, Cecil Hepworth), which treated a kidnapping in a linear fashion similar to that of

The Great Train Robbery.

After the kidnapping, we see each stage of Rover’s journey to find the child, his return to fetch the child’s father, and their retracing of the route to the kidnapper’s lair. All the shots along the route maintain consistent screen direction, so that the geography of the action is completely intelligible

(

12.7

,

12.8

).

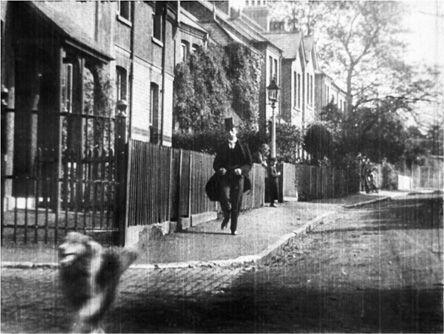

12.7 In

Rescued by Rover,

the heroic dog leads his master along a street from the right rear moving toward the left foreground …

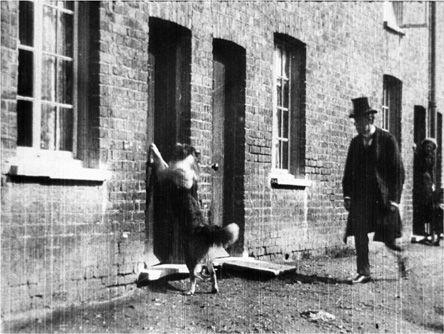

12.8 … and the pair is moving from right to left as they reach their destination.

In 1908, D. W. Griffith began his directing career. Over the next five years, he would make hundreds of one- and two-reelers (running about 15 and 30 minutes, respectively). These films created relatively complex narratives in short spans. Griffith certainly didn’t invent all the devices with which he has been credited, but he did give many techniques strong narrative motivation. For example, a few other filmmakers had used simple last-minute rescues with crosscutting between the rescuers and victims, but Griffith developed and popularized this technique (

6.101

–

6.104

). By the time he made

The Birth of a Nation

(1915) and

Intolerance

(1916), Griffith was creating lengthy sequences by cutting among several different locales. During the early teens, he also directed his actors in an unusual way, concentrating on subtle changes in facial expression (

4.32

). To catch such nuances, he set up his camera closer than did many of his contemporaries, framing his actors in medium long shot or medium shot. Griffith’s films were widely influential. In addition, his dynamic, rapid editing in the final chase scenes of

Intolerance

was to have a considerable impact on the Soviet Montage style of the 1920s.

The refinement of narratively motivated cutting occurs in the work of a number of important filmmakers of the period. One of these was Thomas H. Ince, a producer and director responsible for many films between 1910 and the end of World War I. He devised a unit system, whereby a single producer could oversee the making of several films at once. He also called for tight narratives, with no digressions or loose ends.

Civilization

(1915) and

The Italian

(1915) are good examples of films directed or supervised by Ince. He also supervised the popular Westerns of William S. Hart (

p. 328

), who directed many of his own films.

Another prolific filmmaker of this period (and later years as well) was Cecil B. De Mille. Not yet engaged in the creation of historical epics, De Mille made a series of feature-length dramas and comedies. His

The Cheat

(1915) reflects important changes occurring in the studio style between 1914 and 1917. During that period, the glass-roofed studios of the earlier period began to give way to studios dependent on artificial lighting rather than mixed daylight and electric lighting.

The Cheat

used spectacular effects of chiaroscuro, with only one or two bright sources of light and no fill light. According to legend, De Mille justified this effect to nervous exhibitors as

Rembrandt lighting.

This so-called Rembrandt, or

north,

lighting was to become part of the classical repertoire of lighting techniques.

The Cheat

also greatly impressed the French Impressionist filmmakers, who occasionally used similar stark lighting effects.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

On two of the most important filmmakers of the early classical period, see our entries on William S. Hart in “Rio Jim, in discreet fragments,” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=2590

, and Douglas Fairbanks in “His Majesty the American,” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=3044

.

Like many American films of the teens,

The Cheat

uses a linear pattern of narrative. The first scene

(

12.9

)

introduces the hard lighting but also quickly establishes the Japanese businessman as a ruthless collector of objects; we see him burning his brand onto a small statue. The initial action motivates a later scene in which the businessman brands the heroine, who has fallen into his power by borrowing money from him

(

12.10

).

The Cheat

was evidence of the growing formal complexity of the Hollywood film.

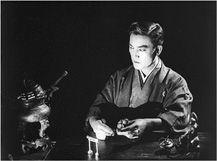

12.9 The opening scene of

The Cheat

introduces the branding motif …