B0041VYHGW EBOK (192 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

“You know, when talkies first came in they were fascinated by sound—they had frying eggs and they had this and that—and then people became infatuated with the movement of the camera; I believe, the big thing right now is to move a handheld camera. I think the director and his camerawork should not intrude on the story.”

— George Cukor, director

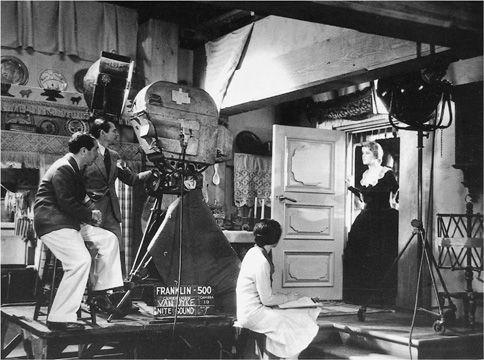

Still, from the very beginning of sound filming, solutions were found for these problems. Sometimes several cameras, all in soundproof booths, would record the scene from different angles simultaneously. The resulting footage could be cut together to provide a standard continuity editing pattern in a scene, with all the sound synchronized. The whole camera booth might be mounted on wheels to create camera movements, or a scene might be shot silent and a sound track added later. Early sound films such as Rouben Mamoulian’s

Applause

(1929) demonstrate that the camera soon regained a great flexibility of movement. Later, smaller cases, enclosing only the camera body, replaced the cumbersome booths. These

blimps

(

12.37

)

permitted cinematographers to place the camera on movable supports. Similarly, microphones mounted on booms and hanging over the heads of the actors could also follow moving action without a loss of recording quality.

12.37 A blimped camera during the early 1930s allowed the camera tripod to be placed on a rolling dolly.

Once camera movement and subject movement were restored to sound films, filmmakers continued to use many of the stylistic characteristics developed in Hollywood during the silent period. Diegetic sound provided a powerful addition to the system of continuity editing. A line of dialogue could continue over a cut, creating smooth temporal continuity. (See

pp. 248

–249.)

Within the overall tradition of continuity style and classical narrative form, each of the large studios developed a distinctive approach of its own. Thus MGM, for example, became the prestige studio, with a huge number of stars and technicians under long-term contract. MGM lavished money on settings, costumes, and special effects, as in

The Good Earth

(1937), with its locust attack, and

San Francisco

(1936), in which the great earthquake of 1906 is spectacularly re-created. Warner Bros., in spite of its success with sound, was still a relatively small studio and specialized in less expensive genre pictures. Its series of gangster films (

Little Caesar, Public Enemy

) and musicals (

42nd Street, Gold Diggers of 1933, Dames

) were among the studio’s most successful products. Even lower on the ladder of prestige was Universal, which depended on imaginative filmmaking rather than established stars or expensive sets in its atmospheric horror films, such as

Frankenstein

(1931) and

The Old Dark House

(1932;

12.38

).

12.38 Heavy shadows, spiky shapes, and eccentric performances mixed a menacing atmosphere with a touch of humor in

The Old Dark Horse.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

Some of these early sound and color films can be hard to find, but we look at some DVD collections that provide lots of information and clips in “All singing! All dancing! All teaching!”

One major genre, the musical, became possible only with the introduction of sound. Indeed, the original intention of the Warners when they began their investment in sound equipment was to circulate vaudeville acts on film. The form of most musicals involved separate numbers inserted into a linear narrative, although a few revue musicals simply strung together a series of numbers with little or no connecting narrative. One of the major studios, RKO, made a series of musicals starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers:

Swing Time

(George Stevens, 1936) illustrates how a musical can be a classically constructed narrative (see

pp. 281

–282).

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

B-movies were a major part of 1930s film production. Our colleagues join us in discussing just what constituted a B-movie in Hollywood in “Bs in their bonnets: A three-day conversation well worth the reading.”

See

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=438

.

More specifically, we consider the Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto series in “Charlie, meet Kentaro”;

During the 1930s, color film stocks became widely used for the first time. In the 1920s, a small number of films had Technicolor sequences, but the process was crude, using only two colors in combination to create all other hues. The result tended to emphasize greenish-blue and pink tones; it was also too costly to use extensively

(

12.39

).

By the early 1930s, however, Technicolor had been improved. It now used three primary colors and thus could reproduce a large range of hues. Though still expensive, it was soon proved to add hugely to the appeal of many films. After

Becky Sharp

(1935), the first feature-length film to use the new Technicolor, and

The Trail of the Lonesome Pine

(1936), studios began using Technicolor extensively. The Technicolor process was used until the early 1970s. (For a variety of examples of Technicolor, running from the 1940s to the 1960s, see 4.1, 4.11, 4.41–4.43, 5.5, and 5.47.)

12.39

Under a Texas Moon

(1930): typical two-strip Technicolor, with mostly orange and green hues.

Technicolor needed a great deal of light on the set, and the light had to favor certain hues. Thus brighter lights specifically designed for color filmmaking were introduced. Some cinematographers began to use the new lights for black-and-white filming. These brighter lights, combined with faster film stocks, made it easier to achieve greater depth of field with more light and a smaller aperture. Many cinematographers stuck to the standard soft-focus style of the 1920s and 1930s, but others began to experiment. By the late 1930s, there was a definite trend toward a deep-focus style.

Mervyn Leroy’s

Anthony Adverse

(1936), Alfred L. Werker’s

The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

(1939), and the Sam Wood–William Cameron Menzies

Our Town

(1940) all used deep focus to a considerable degree. But it was

Citizen Kane

that in 1941 brought deep focus strongly to the attention of spectators and filmmakers alike. Orson Welles’s compositions placed the foreground figures close to the camera and the background figures deep in the space of the shot (5.39). In some cases, the apparently deep-focus image was achieved through matte work and rear projection. Overall,

Citizen Kane

helped make the tendency toward deep focus a major part of classical Hollywood style in the next decade. Many films using the technique soon appeared.

Citizen Kane

’s cinematographer, Gregg Toland, worked on some of them, such as

The Little Foxes

(

12.40

).

12.40 William Wyler stages in depth in

The Little Foxes.

The light necessary for deep focus also tended to lend a hard-edged appearance to objects. Gauzy effects were largely eliminated, and much 1940s cinema became visually quite distinct from that of the 1930s. But the insistence on the clear narrative functioning of all these techniques remained strong. The classical Hollywood narrative modified itself over the years but did not change radically.

There is no definitive source for the term

Neorealism,

but it first appeared in the early 1940s in the writings of Italian critics. From one perspective, the term represented a younger generation’s desire to break free of the conventions of ordinary Italian cinema. Under Mussolini, the motion picture industry had created colossal historical epics and sentimental upper-class melodramas (nicknamed

white-telephone films

), and many critics felt these to be artificial and decadent. A new realism was needed. Some critics found it in French films of the 1930s, especially works by Jean Renoir. Other critics turned closer to home to praise films like Luchino Visconti’s

Ossessione

(1942).

Today most historians believe that Neorealist filmmaking was not a complete break with Italian cinema under Mussolini. Pseudo-documentaries such as Roberto Rossellini’s

White Ship

(1941), even though propagandistic, prepared the way for more forthright handling of contemporary events. Other current trends, such as regional dialect comedy and urban melodrama, encouraged directors and scriptwriters to turn toward realism. Overall, spurred by both foreign influences and indigenous traditions, the postwar period saw several filmmakers beginning to work with the goal of revealing contemporary social conditions. This trend became known as the Neorealist movement.

Economic, political, and cultural factors helped Neorealism survive. Nearly all the major Neorealists—Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, Visconti, and others—came to the movement as experienced filmmakers. They knew one another, frequently shared scriptwriters and personnel, and gained public attention in the journals

Cinema

and

Bianco e Nero.

Before 1948, the Neorealist movement had enough friends in the government to be relatively free of censorship. There was even a correspondence between Neorealism and an Italian literary movement of the same period modeled on the

verismo

of the previous century. The result was an array of Italian films that gained worldwide recognition: Visconti’s

La Terra Trema

(1947); Rossellini’s

Rome Open City

(1945),

Paisan

(1946), and

Germany Year Zero

(1947); and De Sica’s

Shoeshine

(1946) and

Bicycle Thieves

(1948).