B0041VYHGW EBOK (123 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

If the sound bridge isn’t immediately identifiable, it can surprise or disorient the audience, as in the

American Friend

transition. A more recognizable sonic lead-in can create more clear-cut expectations about what we will see in the next scene. Federico Fellini’s

8½

takes place in a town famous for its health spa and natural springs, and several scenes have shown an outdoor or chestra playing to entertain the guests. Midway through the film, a scene ends with the closing of a window on a steam bath. Near the end of the shot, we hear an orchestral version of the song “Blue Moon.” There is a cut to an orchestra playing the tune in the center of the town’s shopping area. Even before the new scene has established the exact locale of the action, we can reasonably expect that the musical bridge is bringing us back to the public life of the spa.

In principle, one could also have a sound

flash-forward.

The filmmaker could, say, use the sounds that belong with scene 5 to accompany the images in scene 2. In practice, such a technique is almost unknown. In Godard’s

Contempt,

a husband and wife quarrel, and the scene ends with her swimming out to sea while he sits quietly on a rock formation. On the sound track, we hear her voice, closely miked, reciting a letter in which she tells him she has driven back to Rome with another man. Since the husband has not yet received the letter, and perhaps the wife has not yet written it, the letter and its recitation presumably come from a later point in the story. Here the sound flash-forward sets up strong expectations that a later scene confirms: We see the wife and the husband’s rival stopping for gas on the road. In fact, we never see a scene in which the husband receives the letter.

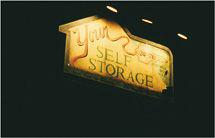

7.50 One scene of

The Silence of the Lambs

ends with Clarice Starling on the telephone, as she mentions a location called the “Your Self Storage facility …”

7.51 … and her voice continues, “… right outside central Baltimore” over the first shot of the next scene, the sign for the Your Self warehouse.

Most nondiegetic sound has no relevant temporal relationship to the story. When mood music comes up over a tense scene, it would be irrelevant to ask if it is happening at the same time as the images, since the music has no existence in the world of the action. But occasionally, the filmmaker uses a type of nondiegetic sound that does have a defined temporal relationship to the story. Welles’s narration in

The Magnificent Ambersons,

for instance, speaks of the action as having happened in a long-vanished era of American history.

As we watch a film, we don’t mentally slot each sound into each of these spatial and temporal categories. But our categories do help us understand our viewing experience. They offer us ways of noticing important aspects of films—especially films that play with our expectations about sounds. By becoming aware of the rich range of possibilities, we’re less likely to take a film’s sound track for granted and likelier to notice unusual sound manipulations.

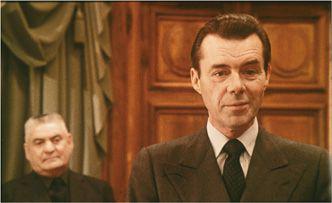

At the start of Alain Resnais’s

Providence,

we see a wounded old man. Suddenly, we are in a courtroom, where a prosecutor is interrogating a young man

(

7.52

).

The scene then returns to the hunt, during which the old man was apparently murdered

(

7.53

).

A cut returns us to the courtroom, where the prosecutor continues his sarcastic questioning

(

7.54

).

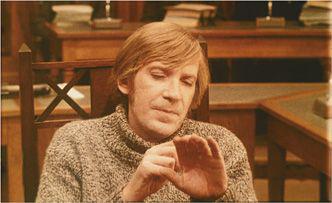

The young man justifies his act by saying that the man was dying and turning into an animal

(

7.55

)

; in

7.53

, we had seen the man’s hairy face and clawlike hands, so now we begin to see the links between the scenes. The prosecutor pauses, astonished, “Are you suggesting some kind of actual metamorphosis?” He pauses again, and a man’s voice whispers, “A werewolf.” The prosecutor then asks, “A werewolf, perhaps?”

(

7.56

).

7.52 The prosecuting attorney in

Providence

questions a man accused of murder …

7.53 … and we see the accused confronting the old man who was killed.

7.54 The prosecutor is seen again …

7.55 … and then the accused man, who explains his actions.

7.56 The prosecutor seems to respond to a mysterious whispered voice—“A werewolf”—that no one else hears.

The whispered words startle us, for we cannot immediately account for them. Are they whispered by an unseen character offscreen? Are they subjective, conveying the thoughts of the prosecutor or witness? Are they perhaps even nondiegetic, coming from outside the story world? Only much later in the film do we find out whose voice whispered these words, and why. The whole opening of

Providence

provides an excellent extended case of how a filmmaker can play with conventions about sound sources.

In the

Providence

sequence, we are aware of the ambiguity immediately, and it points our expectations forward, arousing curiosity as to how the whisperer can be identified. The filmmaker can also use sound to create a retrospective awareness of how we have

mis

interpreted something earlier. This occurs in Francis Ford Coppola’s

The Conversation,

a film that is virtually a textbook on the manipulation of sound and image.

The plot centers on Harry Caul, a sound engineer specializing in surveillance. Harry is hired by a mysterious corporate executive to tape a conversation between a young man and woman in a noisy park. Harry cleans up the garbled tape, but when he goes to turn over the copy to his client, he suspects foul play and refuses to relinquish it.

Now Harry obsessively replays, refilters, and remixes all his tapes of the conversation. Flashback images of the couple—perhaps in his memory, perhaps not—accompany his reworking of the tape. Finally, Harry arrives at a good dub, and we hear the man say, “He’d kill us if he could.”

The overall situation is quite mysterious. Harry does not know who the young couple are (is the woman his client’s wife or daughter?). Nevertheless, Harry suspects that they are in danger from the executive. Harry’s studio is ransacked, the tape is stolen, and he later finds that the executive has it. Now more than ever, Harry feels that he is involved in a murder plot. After a highly ambiguous series of events, including Harry’s bugging of a hotel room during which a killing seems to take place, Harry learns that the situation is not as he had thought.

Without giving away the revelation of the mystery, we can say that in

The Conversation

the narration misleads us by suggesting that certain sounds are objective when at the film’s end we are inclined to consider them subjective, or at least ambiguous. The film’s surprise, and its lingering mysteries, rely on unsignaled shifts between external and internal diegetic sound.