B0041VYHGW EBOK (118 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

As with low- or high-angle framings, we have no recipe that will allow us to interpret every manipulation of fidelity as comic. Some nonfaithful sounds have serious functions. In Alfred Hitchcock’s

The Thirty-Nine Steps,

a landlady discovers a corpse in an apartment. A shot of her screaming face is accompanied by a train whistle; then the scene shifts to an actual train. Though the whistle is not a faithful sound for an image of a screaming person, it provides a dramatic transition.

In some cases, fidelity may be manipulated by a change in volume. A sound may seem unreasonably loud or soft in relation to other sounds in the film. Curtis Bernhardt’s

Possessed

alters volume in ways that are not faithful to the sources. The central character is gradually falling deeper into mental illness. In one scene, she is alone, highly distraught, in her room on a rainy night, and the narration restricts us to her range of knowledge. But sound devices enable the narration to achieve subjective depth as well. We begin to hear things as she does; a ticking clock and dripping raindrops gradually magnify in volume. Here the shift in fidelity functions to suggest a psychological state, a movement from the character’s heightened perception into sheer hallucination.

“[Sound] doesn’t have to be in-your-face, traditional, big sound effects. You can especially say a lot about the film with ambiences—the sounds for things you don’t see. You can say a lot about where they are geographically, what time of day it is, what part of the city they’re in, what kind of country they’re in, the season it is. If you’re going to choose a cricket, you can choose a cricket not for strictly geographic reasons. If there’s a certain cricket that has a beat and a rhythm to it, it adds to the tension of a scene.”

— Gary Rydstrom, sound editor

Sound has a spatial dimension because it comes from a

source.

Our beliefs about that source have a powerful effect on how we understand the sound.

For purposes of analyzing narrative form, we described events taking place in the story world as

diegetic

(

p. 249

). For this reason,

diegetic sound

is sound that has a source in the story world. The words spoken by the characters, sounds made by objects in the story, and music represented as coming from instruments in the story space are all diegetic sound.

Diegetic sound is often hard to notice as such. It may seem to come naturally from the world of the film. But as we saw in the sequence of the Ping-Pong game in

Mr. Hulot’s Holiday,

when the game becomes abruptly quiet to allow us to hear action in the foreground, the filmmaker may manipulate diegetic sound in ways that aren’t at all realistic.

Alternatively, there is

nondiegetic sound

, which is represented as coming from a source outside the story world. Music added to enhance the film’s action is the most common type of nondiegetic sound. When Roger Thornhill is climbing Mount Rushmore in

North by Northwest

and tense music comes up, we don’t expect to see an orchestra perched on the side of the mountain. Viewers understand that movie music is a convention and does not issue from the world of the story. The same holds true for the so-called omniscient narrator, the disembodied voice that gives us information but doesn’t belong to any of the characters in the film. An example is

The Magnificent Ambersons,

in which the director, Orson Welles, speaks the nondiegetic narration.

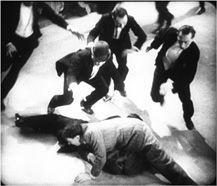

Nondiegetic sound effects are also possible. In

Le Million,

various characters pursue an old coat with a winning lottery ticket in the pocket. The chase converges backstage at the opera, where the characters race and dodge around one another, tossing the coat to their accomplices. But instead of putting in the sounds coming from the actual space of the chase, director René Clair fades in the sounds of a football game. Because the maneuvers of the chase do look like a scrimmage, with the coat serving as a ball, this enhances the comedy of the sequence

(

7.20

).

Although we hear a crowd cheering and a referee’s whistle, we do not assume that the characters present are making these sounds.

7.20 Nondietetic sound effects create comedy in

Le Million

by creating a sort of audio-visual pun.

Entire films may be made with completely nondiegetic sound tracks. Conner’s

A Movie,

Kenneth Anger’s

Scorpio Rising,

and Derek Jarman’s

War Requiem

use only nondiegetic music. Similarly, many compilation documentaries include no diegetic sound; instead, omniscient voice-over commentary and orchestral music guide our response to the images.

As with fidelity, the distinction between diegetic and nondiegetic sound doesn’t depend on the real source of the sound in the filmmaking process. Rather, it depends on our understanding of the conventions of film viewing. We know that certain sounds are represented as coming from the story world, while others are represented as coming from outside the space of the story events. Such viewing conventions are so common that we usually don’t have to think about which type of sound we are hearing at any moment.

At many times, however, a film’s narration deliberately blurs boundaries between different spatial categories. Such a play with convention can be used to puzzle or surprise the audience, to create humor or ambiguity, or to achieve other purposes.

We know that the space of the narrative action isn’t limited to what we can see on the screen at any one moment. The same thing holds true for sound. In the last shot of our

The Hunt for Red October

scene, we hear the officer speaking while we see a shot of just Captain Ramius, listening (

7.13

). Early in the attack on the village in

The Seven Samurai,

we, along with the samurai, hear the hoofbeats of the bandits’ horses before we see a shot of them. These instances remind us that diegetic sound can be either

onscreen

or

offscreen,

depending on whether its source is inside the frame or outside the frame.

Offscreen sound is crucial to our experience of a film, and filmmakers know that it can save time and money. A shot may show only a couple sitting together in airplane seats, but if we hear a throbbing engine, other passengers chatting, and the creak of a beverage cart, we’ll conjure up a plane in flight. Offscreen sound can create the illusion of a bigger space than we actually see, as in the cavernous prison sequences of

The Silence of the Lambs.

It can also shape our sense of how a scene will develop

(

7.21

–

7.23

).

7.21 In

His Girl Friday,

Hildy goes into the pressroom to write her final story. As she chats with the other reporters, a loud clunk comes from an offscreen source, and they glance to the left.

7.22 Hildy and another reporter walk to the window …

7.23 … and see a gallows being prepared for a hanging.

The technique can fill in information very economically. In

Zodiac,

we see the alcoholic reporter Avery wake up after sleeping in his car. As he abruptly sits up, we hear the clink of bottles on the floor; the sound confirms our suspicion that he has spent another night drinking.

Used with optical point-of-view shots, offscreen sound can create restricted narration, guiding us toward what a character is noticing. In

No Country for Old Men,

Llewelyn Moss is holed up in a hotel room with a bag of cash, hiding from his implacable pursuer Anton Chigurh. When he realizes that a tracking device has been hidden among the bills, the narration is limited solely to what Moss sees and hears. He tries calling the downstairs desk; we dimly hear the distant phone ringing, so like him we infer that Chigurh has killed the clerk.

The sonic texture is very detailed, highlighting the slight noises of Moss shifting on the bed and switching off the lamp. Then, against a muted background of wind, we hear steadily approaching footsteps in the hall, accompanied by rapid pinging on a homing device. Optical point-of-view confirms Chigurh’s arrival: we see the shadows of his feet in the crack under the door. Moss cocks his shotgun, creating a click that seems abnormally loud and close. The shadows move away, and we hear the slight creaking of a lightbulb being unscrewed in the hall, eliminating the streak of illumination under the door. The auditory climax of the scene is the metallic burst of the door lock rocketing into the room.

No Country

’s narration has created suspense by restricting both vision and sound to Moss’s range of knowledge. (For a more complex instance, see

“A Closer Look.”

)

Sometimes offscreen sound can make the film’s narration less restricted. In John Ford’s

Stagecoach,

the stagecoach is desperately fleeing from a band of Indians. The ammunition is running out, and all seems lost until a troop of cavalry suddenly arrives. Yet Ford does not present the situation this baldly. He shows a medium close-up of one of the passengers, Hatfield, who has just discovered that he is down to his last bullet

(

7.39

).

He glances off right and raises his gun

(

7.40

).

The camera pans right to a woman, Lucy, praying. During all this, orchestral music, including bugles, plays nondiegetically. Unseen by Lucy, the gun comes into the frame from the left as Hatfield prepares to shoot her to prevent her from being captured by the Indians

(

7.41

).

But before he shoots, an offscreen gunshot is heard, and Hatfield’s hand and gun drop down out of the frame

(

7.42

).

Then bugle music becomes somewhat more prominent. Lucy’s expression changes as she says, “Can you hear it? Can you hear it? It’s a bugle. They’re blowing the charge”

(

7.43

).

Only then does Ford cut to the cavalry itself racing toward the coach.