B0041VYHGW EBOK (50 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

4.60 In

The Sixth Sense,

a flashlight lights the boy’s face from below, enhancing our empathy with his fright as he feels the presence of a ghost.

Top lighting

is exemplified by

4.61

, where the spotlight shines down from almost directly above Marlene Dietrich’s face. Von Sternberg frequently used such a high frontal light to bring out the line of his star’s cheekbones. (Our earlier example from

Asphalt Jungle

in

4.53

provides a less glamorous instance of top lighting.)

4.61 Top lighting in Josef von Sternberg’s

Shanghai Express.

Lighting can also be characterized by its

source.

In making a documentary, the filmmaker may be obliged to shoot with the light available in the actual surroundings. Most fictional films, however, use extra light sources to obtain greater control of the image’s look. In most fictional films, the table lamps and streetlights you see in the mise-en-scene are not the principal sources of illumination for the filming. But these visible sources of light will motivate the lighting decisions made in production. The filmmaker will usually strive to create a lighting design that is consistent with the sources in the setting. In

4.62

, from

The Miracle Worker,

the window in the rear and the lantern in the right foreground are purportedly the sources of illumination, but the many studio lights used in this shot are reflected as white dots in the glass lantern.

4.62 Apparent and hidden light sources in

The Miracle Worker.

Directors and cinematographers manipulating the lighting of the scene will start from the assumption that any subject normally requires two light sources: a

key light

and a

fill light

. The key light is the primary source, providing the dominant illumination and casting the strongest shadows. The key light is the most directional light, and it usually corresponds to the motivating light source in the setting. A fill is a less intense illumination that “fills in,” softening or eliminating shadows cast by the key light. By combining key and fill, and by adding other sources, lighting can be controlled quite exactly.

The key lighting source may be aimed at the subject from any angle, as our examples of lighting direction have indicated. As one shot from

Ivan the Terrible

shows (

4.77

), underlighting may be the key source, while a softer and dimmer fill falls on the setting behind the figure.

4.77 In

Ivan the Terrible,

a character’s fear registers on his face …

Lights from various directions can be combined in any way. A shot may use key and fill lights without backlighting. In the frame from

The Bodyguard

(

4.63

),

a strong key light from offscreen left throws a dramatic shadow on the wall at the right. The dim fill light inconspicuously shows the back wall and ceiling of the set, but leaves the right side of the actor’s head dark.

4.63 Strong key and soft fill light combined in

The Bodyguard.

In

4.64

, from

Bezhin Meadow,

Eisenstein uses a number of light sources and directions. The key light falling on the figures comes from the left side, but it is hard on the face of the old woman in the foreground and softened on the face of the man because a fill light comes in from the right. This fill light falls on the woman’s forehead and nose.

4.64

Bezhin Meadow.

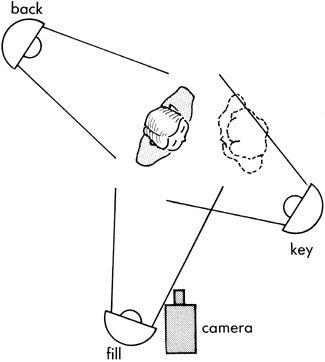

Classical Hollywood filmmaking developed the custom of using at least three light sources per shot: key light, fill light, and backlight. The most basic arrangement of these lights on a single figure is shown in

4.65

. The

backlight

comes from behind and above the figure, the

key light

comes diagonally from the front, and a

fill light

comes from a position near the camera. The key will usually be closer to the figure or brighter than the fill. Typically, each major character in a scene will have his or her own key light, fill light, and backlight. If another actor is added (as in the dotted figure in

4.65

), the key light for one can be altered slightly to form the backlight for the other, and vice versa, with a fill light on either side of the camera.

4.65 Three-point lighting, one of the basic techniques of Hollywood cinema.

“When taking close-ups in a colour picture, there is too much visual information in the background, which tends to draw attention away from the face. That is why the faces of the actresses in the old black and white pictures are so vividly remembered. Even now, movie fans nostalgically recall Dietrich … Garbo … Lamarr … Why? Filmed in black and white, those figures looked as if they were lit from within. When a face appeared on the screen over-exposed—the high-key technique, which also erased imperfections—it was as if a bright object was emerging from the screen.”

— Nestor Almendros, cinematographer

In

4.66

, the Bette Davis character in

Jezebel

is the most important figure, and the

three-point lighting

centers attention on her. A bright backlight from the rear upper right highlights her hair and edge-lights her left arm. The key light is off left, making her right arm brightly illuminated. A fill light comes from just to the right of the camera. It is less bright than the key. This balanced lighting creates mild shading, modeling Davis’s face to suggest volume rather than flatness. (Note the slight shadow cast by her nose.) Davis’s backlight and key light serve to illuminate the woman behind her at the right, but less prominently. Other fill lights, called

background

or

set lighting,

fall on the setting and on the crowd at the left rear. Three-point lighting emerged during the studio era of Hollywood filmmaking, and it is still widely used, as in

4.67

, from

Amélie.

4.66 The three-point system’s effect as it looks on the screen in

Jezebel.