B0041VYHGW EBOK (106 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

To get specific, recall our distinction among temporal order, frequency, and duration. Continuity editing typically presents the story events in a 1-2-3 order. Spade rolls a cigarette, then Effie comes in, then he answers her, and so on. The most common violation of 1-2-3 order is a flashback, signaled by a cut or dissolve. Furthermore, classical editing also often presents only

once

what happens

once

in the story; in continuity style, it would be a gross mistake for Huston to repeat the shot of, say, Brigid sitting down (

6.60

). Again, though, flashbacks are the most common way of motivating the repetition of a scene already witnessed. So chronological sequence and one-for-one frequency are the standard methods of handling order and frequency within the continuity style of editing. There are occasional exceptions, as we saw in our examples from

Hiroshima mon amour, The Godfather,

and

Police Story

(

pp. 233

–235).

What of duration? In the classical continuity system, story duration is seldom expanded; that is, screen time is seldom made greater than story time. Usually, duration is in complete continuity (plot time equaling story time) or is elided (story time being greater than plot time). Let’s first consider complete continuity, the most common possibility. Here a scene occupying five minutes in the story also occupies five minutes when projected on the screen.

“Now nobody trusts the actor’s performance. If an actor has a scene where they are sitting in the distance, everybody says, ‘What are you shooting? It has to be close-up!’ This is ridiculous. You have the position of the hand, the whole body—this is the feeling of a movie. I hate movies where everybody has big close-ups all the time…. This is television. I have talking heads on my television set in my home all the time.”

— Miroslav Ondříček, editor

The first scene of

The Maltese Falcon

displays three cues for

temporal continuity.

First, the narrative progression of the scene has no gaps. Every movement by the characters and every line of dialogue is presented. Second, there is the sound track. Sound issuing from the story space (what we call

diegetic

sound) is a standard indicator of temporal continuity, especially when, as in this scene, the sound bleeds over each cut. Third, there is the match on action between shots 5 and 6. So powerful is the match on action that it creates both spatial

and

temporal continuity. The reason is obvious: if an action carries across the cut, the space and time are assumed to be continuous from shot to shot. In all, an absence of ellipses in the story action, diegetic sound overlapping the cuts, and matching on action are three primary indicators that the duration of the scene is continuous.

A CLOSER LOOK

INTENSIFIED CONTINUITY:

L.A. Confidential

and Contemporary Editing

By the 1930s, the continuity system was the standard approach to editing in most of the world’s commercial filmmaking. But it underwent changes over the years. Today’s editing practices abide by the principles of continuity but amplify them in certain ways.

Most obviously, mainstream films are now cut much faster than in the period between 1930 and 1960. Then, a film typically consisted of 300–500 shots, but in the years after 1960, the cutting pace picked up. Today a two-hour film might have over 2000 shots, and action films routinely contain 3000 or more. The average shot in

The Bourne Ultimatum

lasts about two seconds. Partly because of the faster editing, scenes are built out of relatively close views of individual characters, rather than long-shot framings. Establishing shots tend to be less common, sometimes appearing only at the end of a scene. Telephoto lenses, which enlarge faces, help achieve tight framings, and modern widescreen formats allow two or more facial close-ups to occupy the screen. Also, the camera tends to move very frequently, picking out one detail after another.

The accompanying shots from

L.A. Confidential

show several of these tendencies at work. After arresting three black suspects, Lieutenant Ed Exley prepares to wring a confession from them. The scene takes less than a minute but employs nine shots, two with significant camera movement. (The film contains nearly 2000 shots, an average of four seconds apiece.) Director Curtis Hanson shifts the emphasis among several key characters by coordinating his editing with anamorphic widescreen, staging in depth, close-ups and medium close-ups, rack-focus, and mobile framing

(

6.109

–

6.120

).

Interestingly, the actors make no expressive use of their hands or bodies; the performances are almost completely facial.

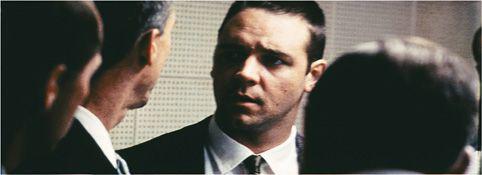

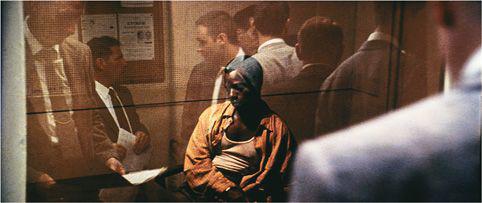

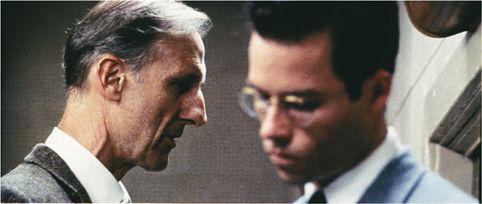

6.109 Shot 1: The scene begins by presenting only a portion of the space. A reflection shows Exley waiting and his colleagues milling about outside the interrogation room. This image singles out the core dramatic action to come—Exley’s brutal confrontation with the suspects.

6.110 Shot 2: A match on Exley’s action of turning gives us a fuller view of the policemen and establishes two other main characters: Jack Vincennes on the left and Bud White in the background, watching. This is only a partial establishing shot; a later camera movement will acquaint us with the layout of the interrogation rooms.

6.111 Shot 3: Hanson underscores White’s presence by cutting to a telephoto shot of him saying that the suspects killed his partner.

6.112 Shot 4: In an echo of the opening framing, Exley now stands at the second interrogation room, seen in another reflection. The shot also reiterates Vincennes’s presence, which will provide an important reaction later.

6.113 The camera tracks with Exley moving right to study the suspect in the third room. White’s reflection can be seen in frame center. The camera movement has linked the three main detectives on the case while also establishing the three rooms as being side by side. At the end of the camera movement, Exley turns, and …

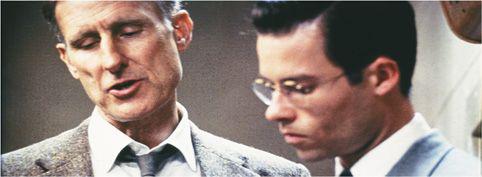

6.114 Shot 5: … a two-shot establishes his superior, Smith, on the scene. As Smith explains that the suspects’ shotguns put them at the murder scene, the camera racks focus to him, putting Exley out of focus.

6.115 Shot 6: A cutaway to White listening—again, a tight facial shot taken with a telephoto lens—reminds us of his presence. He is only an observer in this phase of the scene, but as the questioning heats up, he will burst in to attack a suspect.

6.116 Shot 7: Returning to the two-shot shows Smith demanding that Exley make the men confess.

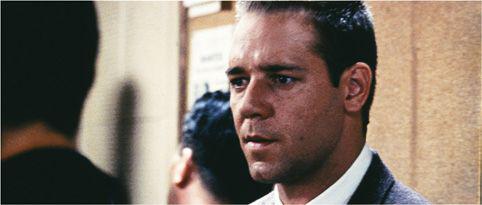

6.117 Shot 8: A reverse-angle on Exley, the first shot in the scene devoted to his face alone, underscores his determination: “Oh, I’ll break them, sir.”