Another Insane Devotion (17 page)

Read Another Insane Devotion Online

Authors: Peter Trachtenberg

My God, who would want that as a pet?

F. had men before she met me, some of whom she saw for a year or more, some of whom she loved. But she's spent most of her adult life alone. I think I have never met anyone more lonely. Her solitude, along with her quiet and general eccentricity, has caused her social awkwardness. For a long time she didn't drive, and she didn't own a car until we bought one together; even in the country, she got around by walking and, because of that, was viewed with pity, condescension, and occasional unease. She was an affront to people's sense of categories. Walking was an

activity of the poor and the health-conscious elderly, and F. was youthful and well dressed. Sales clerks don't know what to do with her. She doesn't get small talk and when strangers try to make it with her, she looks at them with a clinical bafflement that's easy to mistake for disdain. One of the first things she told me about herself was that she was often insulted at parties. At first I doubted herâwhy would anybody do that?âbut as I started going to parties with her, I saw that it was true. Maybe it wasn't actual insults, but people slighted her, seemingly for no reason. She assured me it happened less when I was with her. It was one of the things she liked about being together.

activity of the poor and the health-conscious elderly, and F. was youthful and well dressed. Sales clerks don't know what to do with her. She doesn't get small talk and when strangers try to make it with her, she looks at them with a clinical bafflement that's easy to mistake for disdain. One of the first things she told me about herself was that she was often insulted at parties. At first I doubted herâwhy would anybody do that?âbut as I started going to parties with her, I saw that it was true. Maybe it wasn't actual insults, but people slighted her, seemingly for no reason. She assured me it happened less when I was with her. It was one of the things she liked about being together.

It's true that I'm more socially adroit than she is, more comfortable with the insincerities that ease open the stubborn cupboard drawers of small-town life. The Friday evenings at the restaurant whose bartender used to rake leaves off your front lawn when he was a little kid. The New Year's Eve party held in the dreary strip mall near the entrance to the highwayânot even a strip mall but a cluster of unfrequented small businesses anchored by a diner that's had four or five different managements in the time you've lived hereâone of whose storefronts now turns out to contain a dance club. Who knew, a dance club barely a quarter of a mile from the fencing-and-gazebo barn? In the semidarkness, middle-aged revelers perform the jogging steps of the middle-aged alongside teenage girls in shiny, skimpy dresses and their boyfriends. A bass grunts. Some people are wearing domino masks, which conjures up an image of the orgy in

Eyes Wide Shut.

And like that movie's protagonist, who sees the familiar skin of the world peeled back to reveal its secret sensual anatomy, you realize that these

partygoers are people you know. The man in the snappy black-and-white tuxedo shirt lifts weights beside you at the gym. The woman in the sequined pantsuit owns the dry cleaner's. Her husband always calls you by F.'s last name. What you're supposed to do is give the bartender a good tip and ask him how his mom is. You're supposed to tease the orgiast from the gym: “So

this

is why you been doing all those flies? You wanted to look good for your New Year's date?” F. wouldn't do that; it wouldn't occur to her to.

Eyes Wide Shut.

And like that movie's protagonist, who sees the familiar skin of the world peeled back to reveal its secret sensual anatomy, you realize that these

partygoers are people you know. The man in the snappy black-and-white tuxedo shirt lifts weights beside you at the gym. The woman in the sequined pantsuit owns the dry cleaner's. Her husband always calls you by F.'s last name. What you're supposed to do is give the bartender a good tip and ask him how his mom is. You're supposed to tease the orgiast from the gym: “So

this

is why you been doing all those flies? You wanted to look good for your New Year's date?” F. wouldn't do that; it wouldn't occur to her to.

After we got married, my actual presence at such events became less necessary, since she now wore a wedding band. “People notice that,” she'd say, flashing the ring, “and I can see the relief on their faces. They know how to place me.” She still says it, even now that what we are to each other is uncertain. There are women who find a wedding band demeaning, since it essentially serves as an emblem of possession, a function that was more evident when only women wore them. The ring signifies that the wearer belongs to a certain man and can't be taken from him without consequence. In that sense, it's also a warning device, like a car alarm. It's unclear whether the warning is directed at other men or at the woman herself. But, along the same demeaning lines, you could also compare a wedding band to a pet's ID tag; typically, dogs get a bone-shaped one and cats a silent little bell. Such tags also express ownership and, indeed, often proclaim it, being engraved with the name and phone number of the pet's owner. But their purpose isn't to prevent theft so much as to help find the pet if it gets lost. Pets get lost all the time. Drawn by an interesting smellâin cartoons it's typically portrayed as a vaporous hand

with a beckoning fingerâthey slip their leash or wander out of their yard and soon find themselves on a street they don't recognize, gazing up at the legs of oblivious hurrying strangers. Sometimes they roam farther still, beyond the places where people are. A landscape of rustling underbrush and yellow eyes glinting in the shadows of the trees. A dark wood in which there is no straight path.

with a beckoning fingerâthey slip their leash or wander out of their yard and soon find themselves on a street they don't recognize, gazing up at the legs of oblivious hurrying strangers. Sometimes they roam farther still, beyond the places where people are. A landscape of rustling underbrush and yellow eyes glinting in the shadows of the trees. A dark wood in which there is no straight path.

Â

There's no archaeological record of when men and women began to marry. Given that some form of marriage exists among nomadic peoples like the Tuareg, Kham, and Warrungu, it's likely that humans were marrying before they had much in the way of property. So much for Engels's view of marriage as a bourgeois institution. Say in the beginning its chief purpose was the protection and rearing of small children and the formation of alliances among people who might otherwise be enemies. That rangy fellow with the dead eye and the necklace of dog's teeth wasn't so menacing when you discovered he was the husband of your wife's sister, and you were grateful to be able to call on him when other nomads tried to drive you away from the watering hole. Marriage extended kinship beyond biology, connected you to people who didn't share your blood. In all the early accounts of marriage, the idea of connection is paramount. When God gives Adam a mate, it's not in the interest of his sexual fulfillment. It's because it is not good that the man should be alone.

This period of companionship lasted only a little while. Perhaps it ended with the Fall. Having seen each other

turned inside out like flayed skins, could the man and the woman stand to look at each other again? Could they stand to be looked at? In Masaccio's painting, they walk side by side but don't touch. Both of them are encysted in their shame, and one wouldn't be surprised to learn that once they had wandered a distance out of Eden and begotten their unhappy sons, they parted ways and had nothing more to do with each other. It established a pattern. Men labored with men and went off to war with them; they feasted and got drunk together and sang the kinds of songs men have been singing since they discovered that they sounded better when they were drinking. The women served them, first the food, then the bowls of wine or beer. There was no pretense of fairness. Afterward, they went off by themselves and ate and drank the women's portion and sang songs of their own. At a certain hour of the night, the men and women lay down together. Things went on in this manner, with variations, for the next 10,000 years.

turned inside out like flayed skins, could the man and the woman stand to look at each other again? Could they stand to be looked at? In Masaccio's painting, they walk side by side but don't touch. Both of them are encysted in their shame, and one wouldn't be surprised to learn that once they had wandered a distance out of Eden and begotten their unhappy sons, they parted ways and had nothing more to do with each other. It established a pattern. Men labored with men and went off to war with them; they feasted and got drunk together and sang the kinds of songs men have been singing since they discovered that they sounded better when they were drinking. The women served them, first the food, then the bowls of wine or beer. There was no pretense of fairness. Afterward, they went off by themselves and ate and drank the women's portion and sang songs of their own. At a certain hour of the night, the men and women lay down together. Things went on in this manner, with variations, for the next 10,000 years.

Societies that observe this arrangement are described as homosocial, with men and women inhabiting separate spheres that only narrowly coincide.

In some times and places, the sexes dined together.

Â

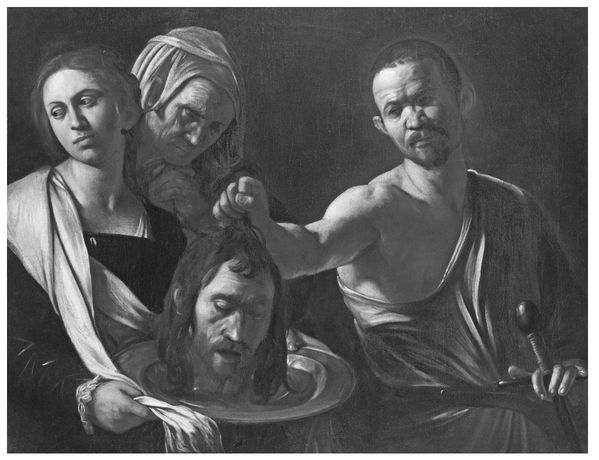

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio,

Salome with the Head of John the Baptist

(London, c. 1607), National Gallery, London. Courtesy of Art Resource.

Salome with the Head of John the Baptist

(London, c. 1607), National Gallery, London. Courtesy of Art Resource.

Sometimes they came together for worship or to attend public entertainments.

But for much of history, the chief area of coincidence was marriage, especially the marriage ceremony, in which a man and woman stood together before their families, under the eye of that God who decreed it wasn't good for man to be alone. From then on, they were one, or at least they were treated as one by their society, that one being, implicitly, male. The paradox was that once the man and the woman had publicly sealed their union, they largely returned to their separate social realms. One can visualize marriage as a smaller version

of the compound giant pictured on the original frontispiece of Hobbes's

Leviathan

.

of the compound giant pictured on the original frontispiece of Hobbes's

Leviathan

.

Â

Abraham Bosse, frontispiece of the first edition of Thomas Hobbes's

Leviathan

(1651). Courtesy of the Granger Collection.

Leviathan

(1651). Courtesy of the Granger Collection.

Instead of being made up of thousands of men, the leviathan of marriage contains a single man and woman. The face it wears in public is a male face; it resembles the husband's face, but it has just one unvarying expression, sober, contented, a little dull. The leviathan appears in public only on rare, mostly ceremonial occasions. The rest of the time, it breaks up into its constituent male and female homunculi, and these spend

much of their time with others of their kind. Or this was the practice until well into the last century.

much of their time with others of their kind. Or this was the practice until well into the last century.

However, even when engaged in her own pursuits, the woman is now identified as belonging toâas being ofâthe leviathan or, for all practical purposes, her husband. It's as if instead of wearing a ring, she were carrying a little mask (I imagine it as being made of gold) with her husband's face on it, and on certain occasions she must hold the face in front of hers and speak from behind it, as if in keeping with Genesis 20:16: “Behold, he is to thee a covering of the eyes.” Depending on the husband's status, this can be advantageous. Witness the courtesies accorded the wives of the baron, the mayor, and the pastor in former times, the wives of celebrities and corporate CEOs today. The prie-dieu embroidered with the family coronet. The personal shopping assistant at Barney's. Of course, it's oppressive for a woman to have to go through the world pretending to be her husband, but the masquerade doesn't just carry privilege: it carries protection. In a man's world, an unmarried woman is up for grabs. She may be raped. She may be robbed. She may be tortured and murdered, even burned alive before crowds that one variously imagines as raucous or dumbstruck by the spectacle of suffering unfolding before them. This was what was done to witches. (Some witches, of course, were married women. In a man's world, finally, any woman is up for grabs, and a husband's protection is about the same as that provided by a fig leaf.)

Other books

Shield of Innocence (Alternate Places Book 4) by P.S. Power

Get Real by Betty Hicks

Love.Lies.Lessons. Tyson & Nakita ( A PKC View Back Story ) by Mumford, Candace

Crush Depth by Joe Buff

All of You by Dee Tenorio

The Hungry Tide by Amitav Ghosh

Rug Burns (Reviving Haven Book 2) by Cyr, Cory

The Tale of Oriel by Cynthia Voigt

Tragedy's Gift: Surviving Cancer by Sharp, Kevin, Jeanne Gere

Did You Read That Review ? by Amazon Reviewers