Another Insane Devotion (28 page)

Read Another Insane Devotion Online

Authors: Peter Trachtenberg

We searched farther and farther from the house, along back roads and footpaths, in people's yards and in a sinister abandoned barn that was always ten degrees colder than it was outside, like a morgue. We put up posters. We stuffed flyers in mailboxes and taped them to the doors of the college dorms:

At night we set traps and in the morning released the irate strays we found inside, each crouched beside an empty can of Friskies like a dragon guarding its hoard. Sometimes we speculated about how long it

must take the captives to get over their initial panic and start eating. It was F. who organized us. Her earlier vagueness might have been a disguise that she had now cast off. But, really, she'd gone through most of her life alone and unaided, with her head down, applying herself to the business of survival. I'd just forgotten that. She had us call every animal shelter within fifty miles. She posted Gattino's picture on animal-finder websites. She consulted psychics. At first only F. did this, since she believes in psychics, or half believes in them, but when one of them told her that she was sensing Gattino near a body of moving water, it was me who burned rubber to the creek a half mile away to pace its banks with an open container of cat food. I came back day after day. It didn't matter what I believed. Once, I called a psychic myself, though she described herselfâkind of sniffilyâas an “animal communicator.” She told me that Gattino was dead, which I reported to F. She told me something else that I did not report: that he was a reincarnation of F.'s father, who had come back to show her how to “let go.” I still think it was a good idea to keep this to myself.

must take the captives to get over their initial panic and start eating. It was F. who organized us. Her earlier vagueness might have been a disguise that she had now cast off. But, really, she'd gone through most of her life alone and unaided, with her head down, applying herself to the business of survival. I'd just forgotten that. She had us call every animal shelter within fifty miles. She posted Gattino's picture on animal-finder websites. She consulted psychics. At first only F. did this, since she believes in psychics, or half believes in them, but when one of them told her that she was sensing Gattino near a body of moving water, it was me who burned rubber to the creek a half mile away to pace its banks with an open container of cat food. I came back day after day. It didn't matter what I believed. Once, I called a psychic myself, though she described herselfâkind of sniffilyâas an “animal communicator.” She told me that Gattino was dead, which I reported to F. She told me something else that I did not report: that he was a reincarnation of F.'s father, who had come back to show her how to “let go.” I still think it was a good idea to keep this to myself.

Most of the psychics told us our cat was dead. It was this that made me trust them. Somebody who wanted to rip us off would have told us that Gattino was alive and could be coaxed back if we burned some candles and left $500 in a shopping bag at the door of St. Sylvia's. I might have done that if somebody had told me to; I might have rolled in a pile of shit on our front lawn. The one time I drew the line was when a half-literate stranger e-mailed F., having gotten her address from a shelter's website, and told her that his friend Samuel had found Gattino and taken a fancy to him and brought him back with

him to Cameroon. All we had to do was wire him the price of a plane ticket, and he'd send him home. I don't remember whether we were supposed to pay for tickets for Samuel and Gattino or just Gattino, but “Cameroon” set off an alarm bellâso might “Belarus” or “Moldova” have doneâand my misgivings were confirmed when we pasted it, along with the terms “Samuel” and “cat” into Google and found the outraged testimonies of people who had sent off the money and never seen their pets again.

him to Cameroon. All we had to do was wire him the price of a plane ticket, and he'd send him home. I don't remember whether we were supposed to pay for tickets for Samuel and Gattino or just Gattino, but “Cameroon” set off an alarm bellâso might “Belarus” or “Moldova” have doneâand my misgivings were confirmed when we pasted it, along with the terms “Samuel” and “cat” into Google and found the outraged testimonies of people who had sent off the money and never seen their pets again.

In winter, we were still searching. Late at night we'd get a call from a security guard at the college who'd seen a one-eyed cat scrabbling in a dumpster. We'd throw coats on over our pajamas, drive fishtailing on the icy roads, and end up in a parking lot where a man in a down jacket shone his flashlight onto the snow. “He was just here.” We'd stand there stricken. The guard would go back to his rounds, and we'd put out a can of cat foodâwe spent a fortune on cat food that yearâand sit in the car with the lights off, hoping that if we waited long enough, Gattino, if it was Gattino, might return. One night I caught a glimpse of a small, thin creature slinking under a parked car. It might have been a cat; it might have been a fox or a stoat. At any other time, I would have been thrilled to spot a wild animal near college dorms where kids from the city were smoking dope and reading Heidegger. But all I wanted to see was our cat. I wanted to bring him to F. like a treasure. I opened the door and stepped out slowly into the cold. I barely broke the membrane between stillness and motion. Many, many minutes later, I reached the car where the creature had hidden. I shone my

light beneath it, then dropped into a crouch to see better. My knees hurt. How had I gotten so old? There was no sign of a cat.

light beneath it, then dropped into a crouch to see better. My knees hurt. How had I gotten so old? There was no sign of a cat.

Outside the airport it was cold, and the city's garish carnival night was full of moving lights. Already I'd forgotten what it was like to be someplace that stayed bright after nightfall, apart from a two-block commercial strip where people went looking for action. No need to look for action here; it was everywhere, as in the interior of a spark chamber restlessly populated with subatomic fauna. Instead, you would have to look for stillness. You might not find it.

A bus took me downtown; a second one brought me across town to the railway station. I felt hopeful and eager. The feelings dimmed a little when I learned the next train wouldn't be leaving for more than an hour. I had the impulse to call F. to tell her not to come pick me up. While waiting, I sat in a deli staring at the immense orange faces of two politicians, a man and a woman, who were debating on TV. Never had I seen teeth so huge or eyes so lambent. The volume was turned down and I was sitting too far away to read the captioning, so I focused on the debaters' facial expressions. I might have been watching the actors in a silent movie, each holding up one or two big feelings for the audience to identify, approve of, and feel in turn. The man looked angry and, briefly, tearful. The woman, who for a pol was uncharacteristically attractive, even sexy, smiled and winked. The gestureâis a wink a gesture?âwas so unexpected that I wondered if I was imagining it.

Who was she winking at? And was it a wink of flirtation or a signal that whatever she told her opponent shouldn't be taken too seriously, she was just gaming Mr. Man, and we, the audience, were in on it? Was that why we should vote for her?

During those months we were looking for Gattino, our lives continued in some distant version. We both worked or tried to work. I screwed up a proofreading job so grotesquely that I offered to reorganize the client's filing system for free, not because I hoped she'd rehire meâshe would have had to be insane to do thatâbut because I wanted to feel less guilty. F. spent a lot of the time on the phone. She spoke with friends. She spoke with her sister, who she believed had psychic powers. She spoke with Wilfredo. She spoke with psychics. Sometimes she'd relay what the psychics had told her: Gattino had drunk some poisonous substance and died in agony. He'd died quietly, curling up into himself as if going to sleep. Once in a while, somebody told her that he was still alive.

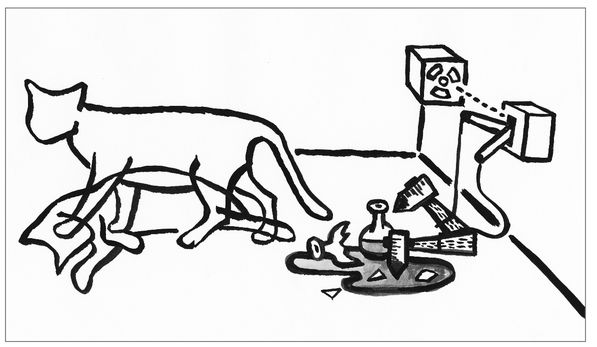

These possibilities seemed equally valid to me. I switched from one to the other with barely a cognitive jolt, and at times I seemed to hold them all in mind at once. Looking back, I'm reminded of the thought experiment of Schrödinger's cat. The experiment is meant to illustrate the unpredictable and fundamentally unknowable behavior of particles on the quantum level. Any attempt to measure that behavior inevitably influences it. Until you look at the meter, you can't know if a deflected electron has veered to the right or the left. Before then, you might as well speak of two ghostly electrons streaking in

opposite directions or maybe a ghostly hybrid particle that moves in both directions at once. It's only when you do the measurement that one of those phantoms evaporates and the other solidifies into a “real” particle occupying an identifiable point in space.

opposite directions or maybe a ghostly hybrid particle that moves in both directions at once. It's only when you do the measurement that one of those phantoms evaporates and the other solidifies into a “real” particle occupying an identifiable point in space.

The physicist Erwin Schrödinger translated this paradox to the macro level. He proposed a scenario in which a cat is placed inside a steel chamber that also contains a tiny bit of a radioactive substance hooked up to a Geiger counter and a vial of cyanide. In the course of an hour, there's a 50 percent probability that an atom of the isotope will decay. If it does, it sets off the Geiger counter, which releases a hammer that shatters the vial of cyanide and kills kitty. If the particle doesn't decay, the cat remains alive. Schrödinger explained that one could visualize the system as “having in it the living

and the dead cat (pardon the expression) mixed or smeared out in equal parts.”

and the dead cat (pardon the expression) mixed or smeared out in equal parts.”

As the diagram above suggests, the cat remains in this smeared, blurred state, equally alive and equally dead, until such time as an observer peers inside the chamber. The observer's eye is what breaks the spell of indeterminacy. Perhaps our cat had become such a ghostly hybrid, not in a sealed box but in the wide world. Only when someone observed him would he solidify into life or death. For the observation to be reliable, however, it would have to be performed by someone who recognized Gattino, not as a generic cat searching for food in the cold and dark but as himself: this cat and no other. I suppose that means he would have to be observed by someone who loved him.

We were both sad, but F.'s grief was of a different order than mine. It admitted no other feeling. In my memory, she is always gazing out the window with sunken eyes. She is always walking out of the house with a sheaf of flyers that she leaves in the same mailboxes where she left some the month before, like a faithful mourner leaving flowers at a grave. My grief was more porous. At times I had the thought that we were making a huge deal about what was, after all, just a cat. I didn't tell F. about this thought, which, even as I had it, felt petty, less indicative of moral discernment than of irritation at lost comforts. Maybe it was also about jealousy, though what could be more pathetic than a live man being jealous of a dead cat, or of a live cat and a dead one smeared out in equal parts? Maybe I wasn't jealous so much as envious of the single-mindedness

of my wife's sorrow. Its purity was lyrical, a moment of loss extending to the farthest horizon. I could only grieve like a husband, pausing to call the oil company to schedule a delivery. It was winter, after all, and very cold, and when Rudy had told us that the heat would only cost $300 a month, he'd been full of shit.

of my wife's sorrow. Its purity was lyrical, a moment of loss extending to the farthest horizon. I could only grieve like a husband, pausing to call the oil company to schedule a delivery. It was winter, after all, and very cold, and when Rudy had told us that the heat would only cost $300 a month, he'd been full of shit.

On one of the first nights after Gattino's disappearance, F. told me that she'd heard a voice in her head saying, “I'm scared.” Some time after that, the voice had returned. Now it said, “I'm lonely.” Late one afternoon about two months later, she told me she'd heard the voice again. It said, “I'm dying,” and then “good-bye.” When she told me this, I let out a groan. I sank to the floor. She'd looked into the chamber and shown me what was inside. We went into her bedroom and lay down together, holding each other, but some part of her felt far away. Maybe it was with Gattino. In retrospect, I can't say how much of my grief was for our cat and how much was for F. So much of what I'd done during those months I'd done for her. It hadn't helped. And, of course, much of that grief was probably for myself, and I clung to F. with what James Salter calls “the simple greed that makes one cling to a woman.”

Other books

The Hustle by Doug Merlino

Max: A Stepbrother Romance by Brother, Stephanie

Re-Vamped! by Sienna Mercer

Birdie by M.C. Carr

Outlaw: Screaming Eagles MC by Kara Parker

The Tree Where Man Was Born by Peter Matthiessen, Jane Goodall

The Lion at Sea by Max Hennessy

Plain Jane & The Hotshot by Meagan Mckinney

Over the Line by Cindy Gerard

The Kill Order by Robin Burcell