The Hungry Tide

Authors: Amitav Ghosh

PENGUIN CANADA

THE HUNGRY TIDE

AMITAV GHOSH

was born in Calcutta in 1956 and raised and educated in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Iran, Egypt, India, and the United Kingdom, where he received his Ph.D. in social anthropology from Oxford. Acclaimed for fiction, travel writing, and journalism, his books include

The Circle of Reason, The Shadow Lines, In an Antique Land,

and

Dancing in Cambodia

. His previous novel,

The Glass Palace,

sold more than a half-million copies in Britain.

The Hungry Tide

has been sold for translation in twelve foreign countries and is also a bestseller abroad. Ghosh has won France's Prix Medici Etranger, India's prestigious Sahitya Akademi Award, the Arthur C. Clarke Award, and the Pushcart Prize. He divides his time between New York and Calcutta, and is a visiting scholar at Harvard University.

Other books by Amitav Ghosh

THE GLASS PALACE

THE CALCUTTA CHROMOSOME

THE SHADOW LINES

IN AN ANTIQUE LAND

THE CIRCLE OF REASON

Amitav Ghosh

T

HE

H

UNGRY

T

IDE

PENGUIN CANADA

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Canada Inc.)

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen's Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi â 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, Auckland, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Published in Penguin Canada paperback by Penguin Group (Canada), a division of Pearson Canada Inc., 2005.

Simultaneously published in the U.S.A. with Houghton Mifflin Company, 215 Park Avenue South,

New York, NY 10003. Originally published in 2004 in the U.K. by HarperCollins Publishers, 77â85

Fulham Palace Road, Hammersmith, London W68JB.

(WEB) 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

Copyright © Amitav Ghosh, 2004

Lines from

Duino Elegies and the Sonnets to Orpheus

by Rainer Maria Rilke, translated by A. Poulin, Jr. Copyright © 1975, 1976, 1977 by A. Poulin, Jr. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Company.

All rights reserved.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Publisher's note: This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Book design by Melissa Lotfy

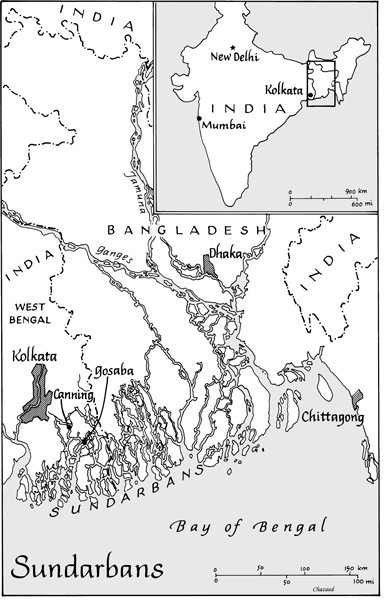

Map by Jacques Chazaud

Manufactured in Canada.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Ghosh, Amitav

The hungry tide / Amitav Ghosh.

ISBN 0-14-301557-5

I. Title.

PR9499.3.G535H85 Â Â 2005 Â Â 823'.914 Â Â C2004-905402-3

ISBN-13: 978-0-14-301557-4

ISBN-10: 0-14-301557-5

British Library Cataloguing in Publication data available

American Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data available

Visit the Penguin Group (Canada) website at

www.penguin.ca

Special and corporate bulk purchase rates available; please see

www.penguin.ca/corporatesales

or call 1-800-399-6858, ext. 477 or 474

For Lila

CONTENTS

Part One

The Ebb:

Bhata

THE TIDE COUNTRY

K

ANAI SPOTTED HER

the moment he stepped onto the crowded platform: he was deceived neither by her close-cropped black hair nor by her clothes, which were those of a teenage boy â loose cotton pants and an oversized white shirt. Winding unerringly through the snack vendors and tea sellers who were hawking their wares on the station's platform, his eyes settled on her slim, shapely figure. Her face was long and narrow, with an elegance of line markedly at odds with the severity of her haircut. There was no

bindi

on her forehead and her arms were free of bangles and bracelets, but on one of her ears was a silver stud, glinting brightly against the sun-deepened darkness of her skin.

Kanai liked to think that he had the true connoisseur's ability to both praise and appraise women, and he was intrigued by the way she held herself, by the unaccustomed delineation of her stance. It occurred to him suddenly that perhaps, despite her silver ear stud and the tint of her skin, she was not Indian, except by descent. And the moment the thought occurred to him, he was convinced of it: she was a foreigner; it was stamped in her posture, in the way she stood, balancing on her heels like a flyweight boxer, with her feet planted apart. Among a crowd of college girls on Kolkata's Park Street she might not have looked entirely out of place, but here, against the sooty backdrop of the commuter station at Dhakuria, the neatly composed androgyny of her appearance seemed out of place, almost exotic.

Why would a foreigner, a young woman, be standing in a south Kolkata commuter station, waiting for the train to Canning? It was true, of course, that this line was the only rail connection to the Sundarbans. But so far as he knew it was never used by tourists â the few who traveled in that direction usually went by boat, hiring steamers or launches on Kolkata's riverfront. The train was mainly used by people who did

daily-passengeri,

coming in from outlying villages to work in the city.

He saw her turning to ask something of a bystander and was seized by an urge to listen in. Language was both his livelihood and his addiction, and he was often preyed upon by a near-irresistible compulsion to eavesdrop on conversations in public places. Pushing his way through the crowd, he arrived within earshot just in time to hear her finish a sentence that ended with the words “train to Canning?” One of the onlookers began to explain, gesticulating with an upraised arm. But the explanation was in Bengali and it was lost on her. She stopped the man with a raised hand and said, in apology, that she knew no Bengali:

“Ami Bangla jani na.”

He could tell from the awkwardness of her pronunciation that this was literally true: like strangers everywhere, she had learned just enough of the language to be able to provide due warning of her incomprehension.

Kanai was the one other “outsider” on the platform and he quickly attracted his own share of attention. He was of medium height and at the age of forty-two his hair, which was still thick, had begun to show a few streaks of gray at the temples. In the tilt of his head, as in the width of his stance, there was a quiet certainty, an indication of a well-grounded belief in his ability to prevail in most circumstances. Although his face was otherwise unlined, his eyes had fine wrinkles fanning out from their edges â but these grooves, by heightening the mobility of his face, emphasized more his youth than his age. Although he was once slight of build, his waist had thickened over the years but he still carried himself lightly, and with an alertness bred of the traveler's instinct for inhabiting the moment.

It so happened that Kanai was carrying a wheeled airline bag with a telescoping handle. To the vendors and traveling salesmen who plied their wares on the Canning line, this piece of luggage was just one of the many details of Kanai's appearance â along with his sunglasses, corduroy trousers and suede shoes â that suggested middle-aged prosperity and metropolitan affluence. As a result he was besieged by hawkers, urchins and bands of youths who were raising funds for a varied assortment of causes: it was only when the green and yellow electric train finally pulled in that he was able to shake off this importuning entourage.

While climbing in, he noticed that the foreign girl was not without some experience in travel: she hefted her two huge backpacks herself, brushing aside the half-dozen porters who were hovering around her. There was a strength in her limbs that belied her diminutive size and wispy build; she swung the backpacks into the compartment with practiced ease and pushed her way through a crowd of milling passengers. Briefly he wondered whether he ought to tell her that there was a special compartment for women. But she was swept inside and he lost sight of her.

Then the whistle blew and Kanai breasted the crowd himself. On stepping in he glimpsed a seat and quickly lowered himself into it. He had been planning to do some reading on this trip and in trying to get his papers out of his suitcase it struck him that the seat he had found was not altogether satisfactory. There was not enough light to read by and to his right there was a woman with a wailing baby: he knew it would be hard to concentrate if he had to fend off a pair of tiny flying fists. It occurred to him, on reflection, that the seat on his left was preferable to his own, being right beside the window â the only problem was that it was occupied by a man immersed in a Bengali newspaper. Kanai took a moment to size up the newspaper reader and saw that he was an elderly and somewhat subdued-looking person, someone who might well be open to a bit of persuasion.