Another Insane Devotion (18 page)

Read Another Insane Devotion Online

Authors: Peter Trachtenberg

There were no great witch hunts in Europe until late in the fourteenth century. During what is called the Dark Ages, the church denounced the belief in witchcraft as superstition, and in AD 794 the Council of Frankfurt made the burning of witches punishable by death. I wonder whether the resurgence of the practice owed anything to the extinction of the Cathar heresy a hundred years before. I don't mean a Halliburton-like conspiracy on the part of the Inquisition, which, having done away with the Cathars, needed another threat to justify its continued operations. By 1480, it already had Protestants for that. But people like to believe in the hidden enemy, the worm in the fruit. Protestants weren't hidden; they nailed proclamations to cathedral doors. The Cathars were hidden, at least some of the time. And what could be more hidden than the woman who lives in your village, maybe even next door to you, distinguished from her sisters only by the fact that she is alone, with no man to vouch for her? For company, she may keep an animal, which is actually a disguised demon. At their esbats or sabbats, witches were said to fornicate with goats, but in the popular imagination, as enshrined in the Halloween displays at Target and CVS, the witch's familiar is usually a cat, a black one.

Â

I think back to the way cats clean their dirty parts, I mean, hunching forward while holding a leg up in the air, presumably to give them fuller access to the area in need of cleaning. What distinguished Biscuit's approach to hygiene, as I said, is the combination of precision and abandon, the geometric line of the suspended leg and the shapeless slouch of the rest of her, which created the impressionâat least it did in meâof a

creature burrowing into herself as if trying to disappear, so intent on disappearing that she'd forgotten about one part of herself, her raised hind leg. And it's this hind leg that I imagine remaining poised in the air after the rest of Biscuit made her impossible exit, like the needle of an invisible compass quivering toward an invisible north.

creature burrowing into herself as if trying to disappear, so intent on disappearing that she'd forgotten about one part of herself, her raised hind leg. And it's this hind leg that I imagine remaining poised in the air after the rest of Biscuit made her impossible exit, like the needle of an invisible compass quivering toward an invisible north.

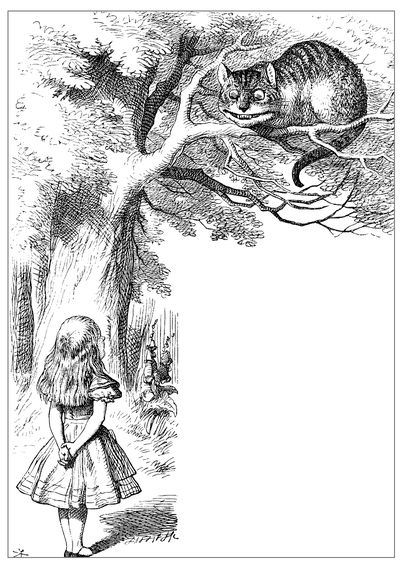

Of course, Biscuit wouldn't be the first cat to vanish and leave a part of itself behind. Lewis Carroll's grinning Cheshire Cat vanishes repeatedly, at first with such abruptness that Alice complains it makes her dizzy.

Â

Sir John Tenniel, “The Cheshire Cat,” illustration from the first edition of Lewis Carroll's

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

(1865). Courtesy of the Granger Collection.

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

(1865). Courtesy of the Granger Collection.

“âAll right,' said the Cat, and this time,” Carroll tells us, “it vanished quite slowly, beginning with the end of the tail, and ending with the grin, which remained some time after the rest of it had gone.”

Carroll may have been inspired by a Cheshire cheese that was made in a mold shaped like a smiling cat. The cheese was cut from the tail end, which would make the grinning head the last part to be eaten. But it's also true that beings seldom vanish all at once. Mostly they do it slowly, almost imperceptibly, until one day you look at the space they occupied and see it's empty. Or almost empty, since it's also the case that most beings leave some trace of themselves behind. A smile lingering above the branch of a tree. The scent on a blouse. A leg pointing at nothing.

Â

We went to events in the city, of course, especially in our early years together, when I still had the loft, and these were more comfortable for F. because she knew most of the people at them. Some of them were her friends, and others were fellow travelers in the worlds she moved through

,

the worlds of readings and art openings and awards dinners where the small, exquisite portions usually went half eaten, not because the food was bad but because people were too excited or too anxious or worried about spilling something on the Armani or being photographed with their mouths gaping to admit a forkful of some other thing, I don't know what, duck confit. I used to take great pleasure in imitating what someone might look like in such a

photo, my head tilted to one side, my eyes popping with greed, my teethâwhich were still very bad back then, back before the dental work I'll be paying off for the rest of my lifeâbared. It always made F. laugh. In fairness to her, she may have been the first of us to do the imitation.

,

the worlds of readings and art openings and awards dinners where the small, exquisite portions usually went half eaten, not because the food was bad but because people were too excited or too anxious or worried about spilling something on the Armani or being photographed with their mouths gaping to admit a forkful of some other thing, I don't know what, duck confit. I used to take great pleasure in imitating what someone might look like in such a

photo, my head tilted to one side, my eyes popping with greed, my teethâwhich were still very bad back then, back before the dental work I'll be paying off for the rest of my lifeâbared. It always made F. laugh. In fairness to her, she may have been the first of us to do the imitation.

F. didn't like all the people she knew at these events; really, she disliked many of them, much more than I did. Well, she knew them. And she understood what drove them, the slow- or quick-fused ambition, the desire for money or fame or beauty and glamour, beauty and glamour especially, always paired, as if one couldn't exist without the other. F. also wanted those things. “If only I had legs like hers,” she'd sigh, gazing with forlorn admiration at a woman across the room. “My whole life would've been different.” But she made no effort to disguise her appetite; she'd tell a stranger about it. She hated the people who pretended to have no appetite and viewed any display of hunger with pitying amusement, even as they peered over your shoulder to see what you had on your plate.

To me, beauty and glamour seemed so unattainable that I could only respond to them with cowed sullenness. F. sensed my discomfort long before I told her about it, which in the beginning I couldn't, and for a long time she'd stay close to me when we went to events where beauty and glamour were likely to be present. The way she did it didn't feel protective so much as proprietary. I was hers, and she wanted to be seen with me. I was always grateful for this. I liked it even better if she went off to talk with somebody she knew for a while, leaving me free to wander around the room or stand in a corner, hoping that I looked mysterious rather than just awkward as I surveyed the

space's other occupants. Few of them, to be honest, were truly beautiful or glamorous, except for the occasional fashion model slipping past like a gazelle that had been imported into a barnyard in the mistaken belief that it could be mated with the livestock. I guess what I liked about F.'s absences was the evidence that she trusted me not to fall apart or try to mount one of the gazelles or get in a fight with a strange bull while she was gone. And I loved to watch her making her way back across the room toward me. When she spotted me, I could see the questing look in her eyes give way to pleasure; I was what she'd been looking for. Sometimes, though, she'd manage to sneak up behind me and grab me around the waist. She's proud of her stealth, and she got a kick out of the little start I gave, though the truth is I often started on purpose.

space's other occupants. Few of them, to be honest, were truly beautiful or glamorous, except for the occasional fashion model slipping past like a gazelle that had been imported into a barnyard in the mistaken belief that it could be mated with the livestock. I guess what I liked about F.'s absences was the evidence that she trusted me not to fall apart or try to mount one of the gazelles or get in a fight with a strange bull while she was gone. And I loved to watch her making her way back across the room toward me. When she spotted me, I could see the questing look in her eyes give way to pleasure; I was what she'd been looking for. Sometimes, though, she'd manage to sneak up behind me and grab me around the waist. She's proud of her stealth, and she got a kick out of the little start I gave, though the truth is I often started on purpose.

Â

“Behold, he is to thee a covering of the eyes.” The speaker is King Abimelech of Gerar. He's addressing Sarah, the wife of Abraham. Many commentators believe he's scolding her, though, really, if he should be scolding anybody, it's Abraham, who passed off Sarah as his sister, under which misimpression Abimelech “took her” (Gen. 20:2) as his wife. “Took”: the word is, to put it mildly, vexing. The Hebrew

laqach

is defined as “to take (in the widest applications),” which could include rape or the sort of nuptial kidnapping that was still being practiced symbolically by the lusty groomsmen of France at the close of the Middle Ages. This is one of two times in Genesis that Abraham pretends he and Sarah aren't married. On both occasions, he's afraid that some powerful figureâbefore Abimelech, it was the pharaoh of Egyptâwill covet his ninety-year-old wife and have

him killed in order to possess her. The subterfuge saves his skin, but at the cost of her chastity, or the near cost, depending on how you read “took.” Abimelech insists he never laid a finger on Sarah. Or, at least, that's what he says when God appears to him in a dream and tells him he's a dead man for taking liberties with her, and even if he's lying, you can hardly blame him. I mean, who knew?

laqach

is defined as “to take (in the widest applications),” which could include rape or the sort of nuptial kidnapping that was still being practiced symbolically by the lusty groomsmen of France at the close of the Middle Ages. This is one of two times in Genesis that Abraham pretends he and Sarah aren't married. On both occasions, he's afraid that some powerful figureâbefore Abimelech, it was the pharaoh of Egyptâwill covet his ninety-year-old wife and have

him killed in order to possess her. The subterfuge saves his skin, but at the cost of her chastity, or the near cost, depending on how you read “took.” Abimelech insists he never laid a finger on Sarah. Or, at least, that's what he says when God appears to him in a dream and tells him he's a dead man for taking liberties with her, and even if he's lying, you can hardly blame him. I mean, who knew?

Most biblical commentaries put forth the view that “a covering of the eyes” refers to the veil that was worn by married women in the ancient Middle East and is still worn there today, and not just by married women. The phrase is syntactically ambiguous. Whose eyes are being covered, the veiled woman's or the lustful viewer's? In either case, the purpose of the veil is the same, and when Abimelech tells Sarah, “He is to thee a covering of the eyes,” he's defining a husband's responsibility to his wife: to be her veil, the protector of her modesty. Not because that modesty is important to him (it doesn't seem to be important to Abraham), but because it may matter to her. That the patriarchy values something doesn't mean that women may not value it too, for reasons that have nothing to do with men's claims on their bodies. Masaccio's Eve shields her breasts and sex without any prompting from Adam, who, locked behind the visor of his grief, may not even notice that she's naked. The patriarchs are often held up as models of marital conductâthis is especially so in fundamentalist Christian circlesâbut Adam seems awfully wishy-washy, and Abraham is even worse. The slights and betrayals. The fling with his wife's handmaid, who flashes her pregnant belly like a big piece of blingâ

Look what your husband gave me

âuntil the wife gets fed up and makes

him cast her out into the desert, and the kid with her. The spineless way he hands Sarah off to any big shot who looks at her twice. Jews aren't supposed to do that. Eskimos are supposed to do that.

Look what your husband gave me

âuntil the wife gets fed up and makes

him cast her out into the desert, and the kid with her. The spineless way he hands Sarah off to any big shot who looks at her twice. Jews aren't supposed to do that. Eskimos are supposed to do that.

We think of modesty mostly in sexual terms, as a reactionâeven an anticipatory reactionâto sexual excitement, an attempt to rein in its lunging surge. Eve covers her sexual parts, not her face. That Adam covers his face might support Freud's belief that women are intrinsically more modest than men, but it also suggests that modesty can be construed more broadly. There is a modesty of the body and a modesty of the soul. Both can be outraged. And there is a social modesty that deters some people from calling attention to where they come from or who their parents were or how much money they have and causes other people to lie about those things; in the latter case, one speaks not of modesty but of shame. Beyond shielding his wife from the gaze and touch of other men, the husband's task may be to help her navigate in social space, for it's there that she is most likely to be shamed. The social realm is where shame lives.

Once, early on in our marriage, I met F. for dinner at a restaurant with our friend Scott. I was late, and when I got there, they were already eating and a second man was sitting across from Scott, in the seat next to mine. I knew him, but not to speak to. He was an old guy who had once done something on Broadway; it made him one of our town's celebrities. Arthur had a wide, loose-lipped mouth framed by the ponderous jowls of a cartoon bulldog. You could imagine them wobbling in outrage or exertion or, less often, from laughter. I had a sense

of him as someone who was used to watching impassively as other people laughed at his jokes but would under no circumstances laugh at anybody else's. Laughter was tribute, and he refused to pay it. Sitting diagonally across from him, F. looked particularly delicate, an impression heightened by the way she cut her food into small, precise bites that she placed in her mouth one by one with small flourishes of her fork while she held up the other hand before her like a paw. I don't know why she eats this way, but to me it's part of her charm.

of him as someone who was used to watching impassively as other people laughed at his jokes but would under no circumstances laugh at anybody else's. Laughter was tribute, and he refused to pay it. Sitting diagonally across from him, F. looked particularly delicate, an impression heightened by the way she cut her food into small, precise bites that she placed in her mouth one by one with small flourishes of her fork while she held up the other hand before her like a paw. I don't know why she eats this way, but to me it's part of her charm.

I remember the drift of the conversation. F. was talking about her appetite, which is robust for somebody her size and used to be even more so. When she was younger, she likes to brag, she could put away a plate of fries and follow it with a milkshake and a piece of pie and never put on a pound. Maybe that's what she said that evening. “That doesn't surprise me,” Arthur said. It sounded like the windup to a joke, but in the next moment, his voice darkened. “I don't doubt you'd eat anything.” The darkness was the darkness of contempt, of loathing. F. stared at him. Somebody else might have said, “Excuse me?” which would have given Arthur the opening to pretend he'd been joking. But F.'s quicker than that, and what she said back was quick and biting. It may have been, “I guess you'd know”; that would have been appropriate. She didn't raise her voice, but her anger was unmistakable. Looking back, I think Arthur had counted on her to be too startled to defend herself. Maybe he was drunk; he had a reputation as a drunk. He told F., “I can just imagine the kinds of garbage you put in your mouth.”

Other books

The Scarlet Slipper Mystery by Carolyn Keene

03 - Call to Arms by Mitchel Scanlon - (ebook by Undead)

Craig Bellamy - GoodFella by Craig Bellamy

Summer Sisters by Judy Blume

Rock 'n' Roll Rebel by Ginger Rue

Eastern Inferno: The Journals of a German Panzerjäger on the Eastern Front, 1941-43 by Christine Alexander, Mason Kunze

Prada and Prejudice by Mandy Hubbard

The Edge of Never by J. A. Redmerski

Christmas With The Houstons (Acceptance #4) by D. Kelly

1805 by Richard Woodman