America's Prophet (26 page)

Authors: Bruce Feiler

Moses then continues to the peak of Mount Nebo, and as “the eternal light of the Glory of God blinds him from the eyes of men,” Charlton Heston turns back toward the camera and raises his right arm in a perfect tableau of the Statue of Liberty. In the final shot of his valedictory film, DeMille crowns his paean to the greatest prophet who ever lived by parading him through the medley of American icons to which he had been compared over the years—the Liberty Bell, Lady Liberty—until he becomes the embodiment of America enlightening the world. The closing image on the screen is the tablets of the law themselves, surrounded by the light of the burning bush, emblazoned with the words “So it was written—So it shall be done.”

Before leaving, I asked Presley whether she thought her grandfather identified with Moses personally.

“He visited Churchill in 1957,” she said. “Churchill was his hero. He called him ‘the greatest man of the twentieth century.’ Churchill received him in bed, and Grandfather told him the story of Moses as if Churchill was Moses—Churchill led his people to freedom, Churchill fought back the Nazis. And the old man burst into tears.

“And I think DeMille, through telling that story,” she continued, “wouldn’t have been conceited enough to think that he was such a figure. But he would have been hopeful enough to think that he had played a small part in doing what Moses had done in helping his country escape the boot of communism.”

I’VE SEEN THE PROMISED LAND

O

NE DAY I

realized I had stumbled into a little-known curiosity of American history: The stained glass in New York City’s churches must be the most unusual in the world. At Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, the twenty-three windows include such non-ecclesiastical figures as Oliver Cromwell and Abraham Lincoln. The stained glass at Manhattan’s Riverside Church includes sixteen images of Jesus and seven of Moses but also the Magna Carta and the Declaration of Independence; the gramophone and the telegraph; tributes to Taoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism; and a window depicting Muhammad, something forbidden in mosques. The Episcopal Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine, the largest church in New York, contains images of a radio and a television, a hockey player and a bowler, as well as Christopher Columbus, Washington’s inaugural, the Gettysburg Address, and the sinking of the

Titanic

. Behind the lectern are nineteen stone carvings, including figures of

Moses and Paul, Washington and Lincoln. The final niche has been left empty, awaiting a suitable figure from the twentieth century.

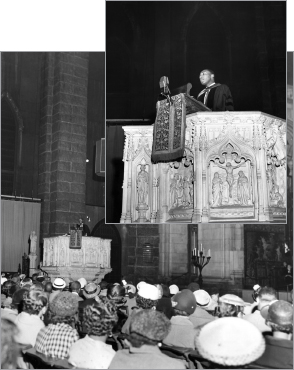

Martin Luther King, Jr., in a never-before-published photograph, delivering his sermon “The Death of Evil Upon the Seashore” at the Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine, New York, May 17, 1956, during the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

(Courtesy of the Archives of the Episcopal Diocese of New York at the Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine)

Odds are it will be Martin Luther King, Jr.

On Thursday, May 17, 1956, the twenty-seven-year-old pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, rose to the pulpit of Saint John the Divine to deliver a sermon at a special interdenominational service in honor of the second anniversary of the landmark

Brown v. Board of Education

Supreme Court ruling, which outlawed segregation in American public schools. The little-known preacher had come to national prominence six months earlier as the head of the Montgomery Bus Boycott triggered by Rosa Parks’s refusal to give up her bus seat to a white man. The 381-day boycott was still going on at the time of King’s address.

The title of his sermon was “The Death of Evil Upon the Seashore.” Standing before an overflow crowd of ten thousand people, he began with a quote from Exodus 14: “And Israel saw the Egyptians dead upon the seashore.” The verse comes from the very end of the Exodus, after the Israelites have crossed the Red Sea, when they look back and see that the Egyptian army has been killed by the returning waters. King’s message was that the Egyptians represent evil “in the form of humiliating oppression, ungodly exploitation and crushing domination.” The Israelites symbolize goodness “in the form of devotion and dedication to the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.” He continued, “The Hebraic Christian tradition is clear, that in the long struggle between good and evil, good eventually emerges as the victor.”

King went on to compare the plight of the Israelites in Egypt and that of colonized Third World residents. At the dawn of the twentieth century, King said, more than half the world’s population lived under the yoke of oppression, including 400 million people in India and Pakistan, 600 million in China, and 200 million in Africa. The world is

now seeing the victory of freedom in this struggle, he said. “The Red Sea has opened, and today most of these exploited masses have won their freedom from the Egypt of colonialism and are now free to move toward the promised land of economic security and cultural development. As they look back, they clearly see the evils of colonialism and imperialism dead upon the seashore.”

Martin Luther King was not always a spellbinding public speaker. In Atlanta, I went to a museum exhibition of the King papers. One item that jumped out was his transcript from Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania. In his first semester in 1948, King got a B+ in preaching and a mere “Pass” in public speaking. The next semester he got a C+ in public speaking, and the following semester a C. He kept getting worse. I wondered, “How would you like to be the teacher who gave Martin Luther King a C in public speaking?”

Scholars have shown that King drew heavily on speeches given by others. “The Death of Evil Upon the Seashore,” for example, has deep parallels with “Egyptians Dead Upon the Seashore,” a sermon given by nineteenth-century abolitionist Phillips Brooks.

Brooks: The parted waves had swept back upon the [Egyptians]…. All that the escaped people saw was here and there a poor drowned body beaten upon the bank, where they stood with the great flood between them and the land of their long captivity and oppression. It was the end of a frightful period in their history.

King: The parted waves swept back upon the [Egyptians]…. As the Israelites looked back all they could see was here and there a poor drowned body beaten upon the seashore…. It was the end of a frightful moment in their history.

As literary scholar Keith Miller describes in

Voice of Deliverance,

a book about King’s rhetoric, multiple sections of King’s speech were taken nearly verbatim from other sources, especially Harry Emerson Fosdick, the so-called “Moses of Modernism,” who was the preacher at Riverside Church. King also drew from sermons he gave with his father in Atlanta applying the lessons of Moses to African American life. But King’s chief source, Miller concludes, was not the published works of others but the folk tradition of American slaves, passed down through oral history. “His equation of black America and the Hebrew people revived and updated the slaves’ powerful identification with the Israelites suffering under the yoke of the pharaoh.”

A century after the Underground Railroad, King once more tapped into the long love affair between Americans and Moses. “Many years ago the Negro was thrown into the Egypt of segregation,” King declared at the climax of his speech. “For years it looked like he would never get out of this Egypt. The closed Red Sea always stood before him with discouraging dimensions. There were always those pharaohs with hardened hearts, who, despite the cries of many a Moses, refused to let these people go.” But then, he continued, a new Moses rose up to liberate blacks, and he mentioned an institution that had likely never before been compared to the Hebrew prophet: the Supreme Court. “One day, through a world-shaking decree by the nine justices of the Supreme Court of America,” King said, “the Red Sea was opened, and the forces of justice marched through to the other side.”

The reaction to King’s New York debut was instantaneous. King labeled the evening “one of the greatest experiences of my life.” The dean of the cathedral called the talk the “greatest sermon” he had ever heard. As the country headed into another deadly showdown over race, America had a new prophet on its hands, and a new

question to ponder: Was Martin Luther King America’s next Moses?

THE HOUSE ON

Auburn Avenue in Atlanta where King was born in 1929 has been turned into a small museum. It has a parlor and a study and is just steps from Ebenezer Baptist Church, where Martin Luther King, Sr., served as pastor and where young “M.L.” found his voice as a leader of God’s New New Israel. Sweet Auburn was one of many middle-class enclaves across the South that blacks in the early twentieth century considered the land of milk and honey. But the laws of the South were promulgated by Jim Crow, not Moses, and blacks once more went looking for a narrative of hope. And once more they turned to the Exodus.

“Fifty years brings us to the border of the Promised Land,” one minister said in 1912. “The Canaan of our citizenship is just before us and is infested with enemies who deny our right to enter.” But fear not, black preachers said; God will hear our suffering and send a Moses to lead the way. As one black pastor recalled, “Our ministers held forth about Moses using the rod to part the waters of the Red Sea. More than once the minister would go on to suggest that there were some ‘Black Moseses’ in the making.”

One of the more vivid black Moseses of the twentieth century was invented by novelist Zora Neale Hurston, a central figure in the Harlem Renaissance. While a student at Barnard College, Hurston studied ethnography and discovered that Moses had been a preeminent figure in voodoo as well as other religions across the Caribbean and Africa. “The worship of Moses recalls the hard-to-explain fact that wherever the Negro is found,” she wrote in 1937, “there are traditional tales of Moses and his supranatural powers that are not in the Bible.” These reverent tales did not spring up spontaneously, she

added. “There is a tradition of Moses as the great father of magic scattered all over Africa and Asia. Perhaps some of his feats recorded in the Pentateuch are the folk beliefs of such a character.” Moses did not become an African American icon because he was featured in the Bible, Hurston suggested; he became a biblical icon after he was featured in African stories.

Hurston flushed out this theme in a 1939 novel,

Moses, Man of the Mountain,

featuring Moses as a voodoo priest. The book opens with a DeMille-like statement from the author: “Moses was an old man with a beard. He was the great law-giver. He had some trouble with Pharaoh about some plagues and led the Children of Israel out of Egypt and on to the Promised Land.” That is the common concept of Moses, she said. But unlike DeMille and many other whites, Hurston wasn’t interested in Moses as a figure of authority; she was interested in Moses as a person who

breaks

the law. Her Moses was a man of confrontation. “All across Africa, America, the West Indies, there are tales of the powers of Moses and great worship of him and his powers,” she wrote. “But it does not flow from the Ten Commandments. It is his rod of power, the terror he showed before all Israel and to Pharaoh.”

In Hurston’s telling, Moses becomes an instrument of black power, the first civil rights activist. He first appears as an Egyptian prince, who earns his reputation as a man of violence and war. But at the crucial moment when he kills the Egyptian overseer for beating a Hebrew slave, Moses changes. “He found a new sympathy for the oppressed of all mankind. He lost his taste for war…. Henceforth he was a man of thought.” Twenty years before Martin Luther King, Jr., Hurston’s Moses becomes a pioneer of nonviolence. He further foreshadows King when, at the moment the pharaoh frees the Israelites, they shout a line from a famed spiritual, “Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, I’m free at last!” King would later

use these same words to conclude his speech at the March on Washington.

Hurston wasn’t alone in anticipating King. C. L. Franklin, arguably the most influential African American preacher through the 1940s and early ’50s, spoke often of the need for a Moses figure to emerge from the black community. Franklin was known as “the Man with the Million Dollar Voice” and was the father of “the Queen of Soul,” Aretha. He was based in Detroit but traveled widely around the country, and he often brought along his daughter to sing. Franklin was among the first to sell his sermons on records, and one of his more famous was “Moses at the Red Sea.” “In every crisis God raises up a Moses,” he said. “His name may be Moses or his name may be Joshua or his name may be David, or his name, you understand, may be Abraham Lincoln or Frederick Douglass or George Washington Carver, but in every crisis God raises up a Moses, especially where the destiny of his people is concerned.” His message: Blacks should not wait for others to lead the way but should seize their own destiny. “The power of deliverance is in our own possession,” he said. “The man who stands and simply cries will never go over his Red Seas.”

Few men put this message of self-reliance into practice more than Franklin’s spiritual protégé, Martin Luther King, Jr. Throughout his career, King stressed that liberation alone was not the destination for blacks. They must also develop standards of dignity and self-respect. “As we struggle for freedom in America,” he told four thousand people in Montgomery that November, “there is a danger that we will misinterpret freedom. We usually think of freedom from something, but freedom is also to something. It is not only breaking loose from some evil force, but it is reaching up for a higher force. Freedom from evil is slavery to goodness.” And this “slavery to goodness,” he insisted, comes with certain duties—to respect oth

ers, to respect yourself, not to strike back, and to practice nonviolence. Freedom, in other words, comes with responsibility. Liberation with self-restraint. Exodus with Sinai. The twin message of America’s founding—revolution paired with constitution—now becomes the watchword of America’s refounding. And once again the language comes from the same source.

“You can’t overemphasize how important Exodus was to us at the time,” said Robert Franklin, one of the leaders of a new generation of African American preachers who grew up during the civil rights era. A native of Illinois (and no relation to C. L.), Franklin is a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Morehouse College, King’s alma mater in Atlanta, who earned a master’s in divinity from Harvard and a doctorate from Chicago. Though he’s taller, with a broader repertoire of languages (including Arabic), Franklin’s narrow mustache, receding hairline, and easy smile lend him a striking similarity to his hero. A week after I visited him in his office, Franklin was named the tenth president of Morehouse.