America's Prophet (11 page)

Authors: Bruce Feiler

“Lawlessness,” he continued, “is the most radical notion of freedom, but that’s not a version that’s compatible with any form of a common life. You might say the Israelites have no common life between leaving Egypt and Sinai. You have a group of freed slaves, with some collective memory, but without a sense of society until they assume the burden of the commandments.”

I mentioned that the moment of covenant seems conservative, compared with the radical moment of liberation.

“Rousseau describes freedom as giving the law to yourself,” he said. “And that’s what supposedly happens at Sinai. When Moses comes down from the mountain, the people say, ‘All that the Lord has spoken we will do.’ That’s when they become a free society. They had been Pharaoh’s slaves, and now they are God’s servants. In biblical Hebrew, the same word,

ebed,

is used to describe the Israelites’ relationship to Pharaoh and later their relationship to God. There’s a kind of bondage in freedom.”

“So if that’s the key moment,” I said, “why is that the least celebrated part of the story? At Passover we celebrate the crossing of the Red Sea. In America we celebrate the Fourth of July. The moment of covenant is overlooked.”

“Right, though in the Jewish calendar there’s Shavuot”—the summer holiday that marks the giving of the Torah to Moses—“and the Constitution does take on a kind of sacred character, even if there isn’t some ritual celebration of its ratification. But there should be.”

“The heart of your argument,” I said, “is that the Exodus is not just a model of revolution; it is a causer of revolution. If that’s the case, is the Exodus a causer of America?”

“It’s certainly an inspiration,” he said. “It’s clear to me there was an enormous excitement in reenacting the story. That feeling of being on God’s side can be dangerous, as we’ve seen recently in American foreign policy, and as we saw with early-American texts that treat the Indians like idolaters and tried to exterminate them. But it’s clear to me the Exodus was a powerful player.”

“So understanding that the story can be used for good and bad, when we look back at the founding moment are we supposed to celebrate it every year, or are we supposed to be wary?”

He chuckled. “You better be wary of it, but that’s probably not a reason for refusing to cheer.”

AT TEN O’CLOCK

on the morning of Thursday, December 12, 1799, George Washington left his home in Mount Vernon, where he was enjoying his retirement from the presidency, and rode out to review his estate. The weather darkened, from rain to sleet to slush. He remained exposed for five hours, and was so late returning that he

went to dinner in wet clothes, rather than keep his guests waiting. The next day, the sixty-seven-year-old general complained of a sore throat and nausea but still ventured out into the snow to mark trees for removal. That evening he retired to his office refusing medicine, saying of his condition that he preferred to “let it go as it came.” When his wife, Martha, chided him for working late, he replied, “You well know that through a long life it has been my unrivaled rule never to put off till the morrow the duties which should be performed today.”

Washington’s condition worsened overnight, and doctors were summoned. Unable to speak, he was fed a mixture of molasses, vinegar, and butter and became convulsive trying to swallow it. He was given vinegar and tea to gargle but almost suffocated. His doctors aggravated the situation by following medical custom and opening veins to bleed him, removing a total of five pints of blood. “I am dying, sir, but am not afraid to die,” he told his doctor. Medical historians now believe he suffered from acute epiglottitis, a rapidly progressing infection of the small gland at the base of the tongue that can become fatal when swelling closes off air passages. The disease, which is treatable with antibiotics, is considered an atrociously painful way to expire.

At four-thirty that Saturday afternoon, December 14, Washington had Martha summon his will, which, among other requests, freed his slaves (though not hers). Around 10

P.M

. he experienced a respite. He asked that his corpse be kept for three days before being interred, a request that some consider a harkening back to fears that Jesus may have been buried alive. No preacher was summoned to Washington’s side. Before eleven, he uttered his last words, “’Tis well,” and his hand fell to his side. “’Tis well,” Martha echoed. “I have no more trials to pass through. I shall follow him soon.”

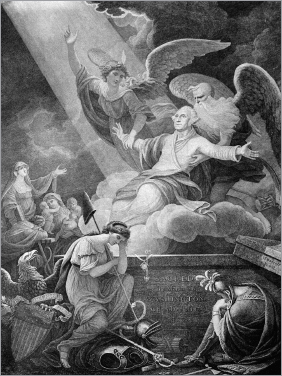

The Apotheosis of Washington,

depicting the deceased president, supported by Father Time, being conducted heavenward by an angel, leaving below symbols of the American republic. Print by John James Barralet, 1800.

(Courtesy of The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association)

Washington’s will stated his express desire that his corpse “be interred in a private manner, without parade, or funeral oration.” His modest request, like so many before it, went ignored. Washington’s Masonic lodge in Alexandria was invited to make arrangements for a funeral march. At 3

P.M

. the following Wednesday a procession set off from Mount Vernon consisting of cavalry, foot soldiers, and a military band. The general’s steed walked with an empty saddle. His body was carried to a small tomb on a bluff below the mansion. The Reverend James Muir performed an Episcopal burial ceremony and members of the lodge performed Masonic burial rituals. Eleven artillery rounds were fired over the Potomac, a veil was lifted over Washington’s face, and the first president of the United States was buried, Reverend Muir wrote, as “the sun was setting.”

For all the dignity of this ceremony, it created a number of challenges. The new country had never lost a man of such stature, and the public craved communal bereavement. Newspapers printed special editions with black borders, women purchased commemorative jewelry, men wore black armbands. Grief was so widespread that merchants complained of shortages of black fabric as late as the following July. But the focal point of the public commemoration was a series of mock funerals. The first was held in the nation’s capital, Philadelphia, on December 26. The morning began with cannon fire and was followed by a long procession of exactly the kind Washington had feared, featuring a riderless horse with an empty saddle, holsters and pistols dangling at its side, and boots reversed in the stirrups. The horse’s head was festooned with black and white feathers; an American eagle was displayed on its breast. Pallbearers carried an empty bier, and Congressman Henry Lee delivered his famous valediction: “First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

In the coming months, city after city held similar faux funerals.

Four hundred forty orations were given, many of which were published. Of those, 346 survive. Robert Hay of Marquette University surveyed the existing eulogies in 1969 and concluded that the common perception that they drew largely on classical references was false. “Page for page, religious themes far outnumber classical themes,” he wrote. Specifically, mourners drew on themes from the Hebrew Bible. A study of references concluded that of the 120 biblical texts used in discourses, only 7 came from the New Testament, and of those, 4 were references to Old Testament characters. One figure was mentioned above all others. “Washington was compared favorably to all the outstanding biblical, classical, and modern heroes,” Hay writes, “but no analogy was so well developed as the contention that the departed leader had truly been a Moses for America.” As many as two-thirds made this comparison.

Far from passing references to Moses, many of these orations included extensive comparisons between the “first conductor of the Jewish nation” and the “leader and father of the American nation.” Some went on for dozens of pages arguing that Washington “has been the same to us, as Moses was to the Children of Israel.” The single biggest theme was that both men had been commissioned by God. “Kind Heaven,” one orator said, “pitying the servile condition of our American Israel, gave us a second Moses, who should (under God) be our future deliverer from the bondage and tyranny of haughty Britain.” Orations compared the births of both men, pointing out that Moses was born in Goshen, “one of the best provinces” of Egypt, while Washington was born in Virginia, “well known for its profusion and wealth.” One preacher even argued that both men had been mama’s boys. As a baby, Moses was hidden by his mother for three months, while “the future hero of AMERICA,” fatherless since age ten, was destined for a future of lax morals on a British

naval man-of-war. “But fortunately for himself, and for the world, he was soon released from that corrupting, hazardous employment by the earnest solicitations of his affectionate mother.” Providence “snatched him from the brink of ruin, in almost as singular a manner as he did the Hebrew child.”

The orations naturally focused on the parallels between the Israelites’ deliverance from Egypt and the Americans’ emancipation from Britain. Both Moses and Washington, eulogizers insisted, were trained in the art of war, were roughly the same age when they led their people to freedom, and conducted similar numbers to freedom. The age issue is a canard, as Moses dies forty years after the Exodus at age 120, but the population comparison is more apt. The population of the United States in 1776 was between 2.5 and 3 million, while Exodus says Moses led 600,000 men to freedom, which with women and children could easily reach the same number. But orators were more interested in poetry than mathematics. “Moses led the Israelites through the Red Sea; has not Washington conducted the Americans thro’ seas of blood?” As one minister told the Masonic lodge in Cooperstown, New York, “He who had commanded Moses at the Red Sea, also inspired Washington on the banks of the Delaware.”

The most frequently cited comparison was also the most problematic: the deaths of the two leaders. Moses, of course, is denied entry into the Promised Land. After a “face to face” meeting with God on Mount Nebo, he dies in the wilderness and is buried in an unmarked grave. How could Washington be compared to Moses in this regard, considering that he actually led his people into the Promised Land?

One orator offered a twist by explaining that both men were stopped just short of their respective

capitals,

invoking Washington, D.C., then under construction. “A few steps more & the Israelitish

nation would have pitched their government in Canaan. A few steps more and the American nation would have pitched their government in the City of Washington.” But others suggested that the difference in their deaths suggests that Washington was actually superior to his Israelite predecessor. “Moses conducted the Israelites in sight of the promised land; but, Washington had done more, he has put the Americans in full possession.” One eulogizer in Massachusetts went even further, calling Moses “the Washington of Israel.”

At the end of America’s second century, the death of George Washington provided the country with yet another opportunity to publicly reaffirm the connection between its own destiny and the fate of the Israelites in the Bible. At a time when the country was involved in a naval war with Napoléon and a domestic political showdown between Whigs and Federalists, the mourning of Washington offered a rare moment of national renewal when anxious Americans could reassure themselves that they were still God’s chosen people. If God had sent them a second Moses, surely he would uphold his end of the covenant and continue to bless the United States.

And while many of the comparisons between the two deliverers might have been stretched to make a point, one parallel between the two men is striking. Biblical Israel and God’s New Israel were formed on the twin shoulders of liberation and law. In both cases, one man was present at both moments. Both men had the unusual combination of skills—leadership and humility, fortitude and diplomacy—that could serve them well in dramatic moments of confrontation as well as years of slowly building a people. Beloved founders, both could have clung to power but resisted the temptation to turn their nations into monarchies. Reticent speakers, both left behind some of the most quoted words ever spoken.

But for all their similarities, there was one enormous difference that separated them, and it’s a chasm that few people mentioned in

the public orations around Washington’s death. Washington may have led his people from slavery to freedom, but he left a huge population living amidst the chosen people who were still being held as slaves. Somehow God’s New Israel, having just left Egypt, had become God’s New Egypt. If America was going to fulfill its promise in the century after its great liberator died, it first had to confront its own moral paradox and raise up a new kind of Moses.

LET MY PEOPLE GO

T

HE MUD ALONG

the Ohio River has memory. Just beneath the storied town of Ripley, the dark, glutinous sludge catches everything from driftwood to tractor tires to deer antlers. Standing in the guck just after eleven o’clock on a Tuesday night in late autumn, I hear the steady ripple of crickets and birds. A sycamore hangs over the water. The bank is so steep here that I can barely see the houses along Front Street. The wind stings my face, and the weather feels like it’s changing. Winter is coming, the time of year when ice flows along the shore and, on occasion, the river freezes solid. In the decades before the Civil War, these months were the time when shadowy figures emerged from the brush on the Kentucky side and made their way across the slippery surface into the free state of Ohio. For millions of Africans enslaved in the South, Ohio was the Promised Land. And the Ohio River was the Jordan. As one slave spiritual promised:

I’ll meet you in the mornin’,

Safe in de promised land,

On the other side of the Jordan,

Boun’ for de promised land.

Ripley, in the southwest corner of the state, sits on the most famous bend of the Ohio and is the town some believe is the home alluded to in the spiritual “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” (

“Comin’ for to carry me home”

). Ripley also was a focal point in the use of Moses in antebellum America. If Moses was a unifying presence during the Revolutionary era, a generation later he got dragged into the issue that most divided the country. Moses was born a slave. Later he gave up the comforts of wealth to slay a wicked overseer. And still later, he walked away from a peaceful life with his wife and son to confront the greatest slave master who ever lived.

For slaves, Moses was more than just a figure in the Bible. He became a leader of the emerging black nation within the nation. And he provided the blueprint for the famed living metaphor of nineteenth-century America, the Underground Railroad. The generation-long struggle to shuttle slaves from the South to the North is an enticing example of American ideals and pluck. But mostly it’s a human story, of individuals, many with no historic connection to the Bible, who took the central story of that book and transformed it into a narrative of hope. The Founding Fathers chose the Exodus as their theme in an attempt to make their lives better. The slaves needed it to make their lives worth living.

God did say to Moses one day

Say, Moses, go to Egypt land,

And tell him to let my people go.

The river sounds fade as I reach the top of the bank, and the fetid smell of the mud gives way to the gentle perfume of fresh-cut grass and chrysanthemums on the porch. The wooden town houses and brick mansions that line the river are from bygone eras, Georgian, Victorian, Queen Anne. Some have lace curtains in the windows. A few have candles. I see a gas lantern. The houses remind me of patrons, dressed up in costumes from different decades, sitting in box seats overlooking the theater of the river. A light on one of the porches suddenly flashes on, and I wonder if people might begin to wonder why I’m prowling around here near midnight.

My plan is to re-create one of the more daring stretches of the

Underground Railroad, by tiptoeing through the residences along the Ohio, slipping in between the shops of Main Street, then climbing straight up a tree-shrouded ridge to the safe house that was known across a dozen states from 1829 to 1860 for the beacon that shone in its window and its open door to fugitive slaves. But a few steps in and I’m already feeling nervous. I’m not illegal. No bounty hunters are chasing me. I’m carrying a cell phone, a BlackBerry, and a spare hundred-dollar bill to bail my way out of trouble, if necessary. Yet still I’m scared.

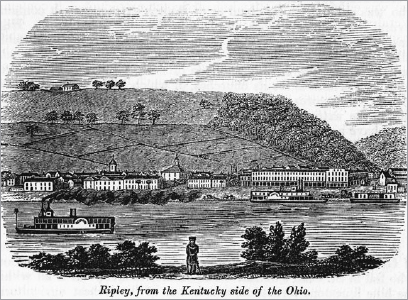

Ripley, Ohio, as depicted in a nineteenth-century woodcut, from the Kentucky side of the Ohio River. The Rankin House can be seen at the top of the hill, overlooking the town. Originally published in 1847. (

Courtesy of The Union Township Public Library, Ripley, Ohio

)

I have been told that alleys run in between the houses of Front Street, perpendicular to the river. They are overgrown and dark, and I’m trying to figure out which one is safe. I come across a sign that marks the birthplace of Senator Alexander Campbell, “doctor, merchant, and early anti-slavery leader.” Campbell was a Virginian who moved to Ohio in 1803, freed his slaves, and served as U.S. senator. “He’s considered one of the pioneers of the abolitionist movement,” the sign says. If that’s the case, he must have helped a fleeing victim or two. I choose the alley alongside his house.

Before I’ve gone fifty yards a dog starts howling. I jump back. The dog races to the fence that separates us and follows me up the alley, leaping and snapping across the barbed wire. I pick up my pace. Suddenly a light switches on. I’ve been on dry ground for less than ten minutes, and already I’ve made what would have been a catastrophic mistake. My freedom would have ended here.

I scoot out of view and soon come to a dirt road and a small barn. Each house has a small backyard and some kind of shed, cabin, or storage facility, perfect for stashing fugitives. The next paved road I come to is Main Street, Route 52, part of the Ohio River Scenic Byway that stretches from Cairo, Illinois, to Ohio’s West Virginia border. In between it passes towns with names like Friendship, Utopia, and Rural. I wait beside the Ripley Museum until the few cars

pass, then scurry across the street, in between the Church of the Nazarene and the Masonic lodge. Soon I come to the Presbyterian church that housed the pulpit of John Rankin, the pioneering abolitionist. His restored home is my destination.

Behind the church, I climb a small wall and find myself in an open yard. I think it’s public property, but I’m not sure. Another dog barks as an American flag flutters in the breeze. A woman steps outside and invites her barking dog into the house. “Does everybody in Ripley have a dog?” I wonder. Ah, no. There’s someone with a cat. I begin my hunt for the wooden stairs that will take me to the top of the hill.

For all the self-congratulation about America being God’s New Israel, a bit of Old Egypt—slavery—was built into the country from its inception. The first twenty African slaves were sold to Jamestown settlers in 1619. Even before the Pilgrims spoke of breaking away from the English pharaoh, real slaves in the colonies were groaning under more immediate hardships. The African slaves became part of a larger network of enslaved Indians and even European whites, who were kidnapped and shipped to the colonies. But as rice and tobacco farming expanded in the colonies, the number of African slaves exploded, reaching 44 percent of the population of Virginia by 1750 and 61 percent of South Carolina. The “Negro Business,” wrote Joseph Clay of Savannah, “is to the Trade of the Country as the Soul is to the Body.” By 1790, the number of slaves living in the United States was 697,647, making up 17 percent of the population.

Few whites had illusions about the horrors of slavery. Thomas Jefferson called the institution a “hideous evil” and chastised freedom fighters “who can endure toil, famine, stripes [lashes], imprisonment, or death itself” fighting for their own liberty, but who still impose bondage “one hour of which is fraught with more misery

than ages of that which he rose in rebellion to oppose.” Yet Jefferson kept slaves himself, and believed that black Africans were inferior and had a “strong disagreeable odor.” He even fathered children with his slave Sally Hemings.

Others, though, put their distaste into action. As early as 1641, Massachusetts forbade slavery, except for prisoners of war. By the 1780s, Quakers formed a committee for banning the “execrable traffic” of slaves. Benjamin Franklin, once a buyer and seller of slaves, became an abolitionist. A Vermont judge wrote that he would accept one person’s ownership of another only with a “bill of sale from God Almighty.” By the end of the eighteenth century, Delaware, Virginia, Maryland, the Carolinas, and Georgia all banned the importation of African slaves, while most northern states passed laws mandating gradual emancipation. The movement to undermine the institution was beginning to gain momentum.

I REACH THE

base of Rankin Hill, where some teenagers are riding bikes. I can’t believe they are out at this hour. I walk the length of the road and reach a dead end, so I double back, past the dogs and the cat, to the house with the American flag. I spot what appears to be a path and follow it. Suddenly trees envelop me. As I begin making my way up a slope, the sound of grasshoppers fills my ears and I’m moving much more slowly. I come to a patch of dead leaves, and my every step is incredibly loud. A shriek of foliage. “Where are the stairs?” I wonder.

At the end of a patch of dirt and mulch, I spot the hint of a wooden structure. I’m under a full canopy in complete darkness. This is totally foolish and a tad dicey, I tell myself. Assuming these are the stairs to the Rankin House, I begin to climb, but the treads

haven’t been repaired in years and some splinter beneath my shoes. Then suddenly the stairs end, and I’m back in roots and mud. I’m breathing heavily now. If anyone had been anticipating fugitives, this is surely where they would have waited. The only way to proceed is on all fours. My hands are riddled with splinters. Sweat drips into my eyes. Finally I come to a second set of stairs and start to climb, counting

one, two, three

. These steps are firmer under my feet.

Ripley, Ohio, is located 250 miles south of the Canadian border in a stretch of hilly woodlands once known as the Imperial Forest. With its plum river location, Ripley emerged as an economic powerhouse in the early 1800s. It became so wealthy that during the panic of 1837, the town sent money to help bail out New York banks. Yet Ripley became best known as ground zero in the antislavery movement, the “hell hole of abolition.”

For all the hand wringing over slavery, the institution’s pivotal role in the nation’s economy only expanded in the nineteenth century with the growth of cotton as a major cash crop. Importing slaves was banned in 1808, but the existing population ballooned, more than doubling to two million by 1830, then doubling again by the Civil War. Though the Underground Railroad was neither unified nor centralized, it was the most comprehensive attempt to undermine this behemoth and was the greatest movement of civil disobedience since the Revolution. Modern estimates suggest that in the six decades after 1800, between 100,000 and 150,000 slaves received assistance from the network.

John Rankin was Ripley’s most controversial resident and Ohio’s main conductor. One scholar calls him a “moral entrepreneur,” who brilliantly mined the hearts and minds of southern Ohio and molded them into an underground army. A native of Tennessee, Rankin was raised a strict Calvinist but was transformed by the revivals of the Second Great Awakening that reached across the Appalachians in

1802 and 1803. “A wonderful nervous affection pervaded the meetings,” Rankin wrote. “Some would tremble as if terribly frightened; some would have violent twitching and jerking; some would fall down suddenly as if breathless and lie for hours.”

The Rankin Family, 1872: the Reverend John Rankin is seated in the center of the bottom row; his son, John, Jr., is standing immediately behind his father’s right shoulder.

(Courtesy of The Union Township Public Library, Ripley, Ohio)

Rankin reacted by reading and rereading the Bible, committing large parts of it to memory. He became a minister but was pushed out of the South for using the Bible to teach “incendiary ideas” about slavery. On New Year’s Eve 1822, Rankin, along with his wife, three sons, and the family’s last remaining fifty dollars, boarded two skiffs and crossed the icy Ohio to Ripley. With a population of 421,

Ripley had not yet experienced the prosperity it would soon enjoy, and Rankin remained restless. “Something good would eventually come from Ripley,” his wife assured him. That something came two years later in a letter Rankin received from his brother Thomas, who announced that he had come into money and purchased slaves. Rankin was disgusted and poured out his ire in a series of twenty-one letters over the next thirteen months. The letters were later printed in the Ripley

Castigator

and made their way to the man who became the country’s leading abolitionist. William Lloyd Garrison credited them with his entry into the movement and reprinted them in the

Liberator

. Rankin’s letters were eventually published in a book that went through eighteen different editions.