All the King's Cooks (21 page)

Read All the King's Cooks Online

Authors: Peter Brears

41.

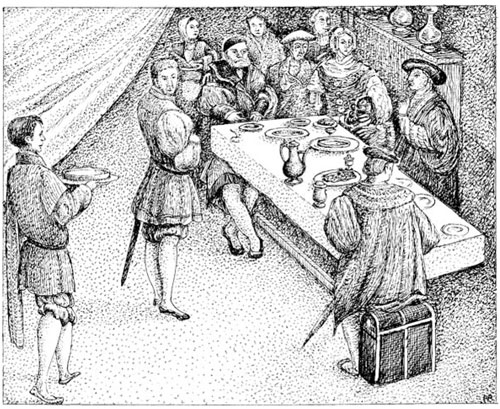

Dining in Chamber

There are no contemporary illustrations of the nobles dining in the Council and Great Watching Chambers, but this detail shows them being served in a tent at ‘The Field of the Cloth of Gold’. It is interesting to speculate whether the figure at the end of the table is Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk and Lord Great Master. It bears a certain resemblance to him, and his appearance here, close to the unique representations of the Kitchen, Boiling House, Bakehouse and Buttery which he controlled, would be most appropriate.

Since the tables were only set up at mealtimes, they lacked the thick tops and solid frames of later periods, but instead would have relatively light planked tops, supported at intervals on trestles. Each trestle had one horizontal bar into which three mortices were cut, one at one end and two at the other, at slightly outward-splaying angles. Once the tenoned ends of the three legs had been inserted in the mortices, each trestle stood really firm on the floor, but once the weight of the table-top had been removed the legs could be easily pulled out, reducing the trestle to four short, interchangeable bars ideal for stacking in any convenient place

3

The yeoman and groom ewerers for the King’s mouth then laid the cloth and prepared the ewery board for hand-washing, leaving the gentleman usher to supervise the setting of the table with silverware, rather than the gold used by the King, brought up from the scullery.

4

Manchet and cheat loaves now arrived from the pantry, wine, beer and ale from the butteries, and the food from the Lord’s-side dresser. Contemporary books of manners suggest that on taking their places, the Lord Chamberlain and his companions would have found everything they needed set out before them.

5

The silver trenchers – or shallow plates – probably had smaller flat, round wooden trenchers placed inside them to provide a good cutting service and also to protect the polished silver from serious damage. One contemporary set ordered for Sir Thomas Brudenell was described as having ‘round trenchers of silver … of 6 ounces [175g] the piece … to lay a wooden trencher in the midst, as ye know the manner is, and about the edge would be some pretty print or work’.

6

To the right of the trencher would lie a silver spoon, and perhaps a narrow, sharp-pointed eating knife – although it was customary for everyone to carry his own in a sheath hung from his belt – and above it, a drinking cup of silver or perhaps fine Venetian glass. To the left lay a manchet loaf and a fine linen damask napkin measuring some 45 by 27 inches (114 by 68.5cm), folded two or three times along its length and then probably crosswise to form a neat rectangle.

7

After grace, each diner opened his napkin into a long strip and placed it either over his left shoulder or across his left forearm, for its purpose was simply to dry the lips before and after drinking rather than as a protective overall for messy eaters. He would then pick up his manchet or cheat loaf in his left hand, place it on

his trencher, slice it horizontally through the middle, cut the top into four strips and reassemble it back in its place as if was whole, and then cut the bottom into three strips and similarly reassemble it crust uppermost alongside.

8

When the pottage arrived, he spooned it up from the communal dish served to each mess. He might break off a piece of bread and dip it into the dish to absorb the liquid, then eat it with the spoon, but bread could not be crumbled into the dish because this would spoil it for others.

9

Once each diner had taken his share of the pottage he would clean his spoon with a piece of bread, which he would then eat, leaving the spoon clean for eating other dishes.

When the main course arrived, he used the same method for eating the semi-liquid dishes, for the rich gravy accompanying roasts and for the succulent juice-soaked ‘sops’, or bread cubes, on which many meats and fish were presented. For vegetables and cereals such as frumenty or rice, he could spoon a quantity on to his trencher, to accompany the meats, always being careful to wipe the spoon clean on a piece of bread before moving on from one dish to another. Solid dishes of meat and fish, which came to the table in mess-sized joints, required a different approach – identical to that used by the carver at ceremonial meals.

10

The matter of greatest importance was the use of the right and left hands. In essence, only the left hand could touch the communal dishes, leaving the right solely for gripping the personal knife or spoon or for lifting food to the lips with the fingers.

11

In this way there could be no risk of any dish being contaminated by anyone’s saliva. When a joint was served to a mess, the diners, probably giving precedence to the senior amongst them, took hold of the piece they wanted with the thumb and first two fingers of the left hand, cut it from the joint using their knife similarly held with the thumb and first two fingers of the right hand, the butt inside the palm. Still gripping it with the left hand, they would place the piece of meat on their trencher, holding it there until they had cut it up into small mouthfuls. If salt was required, it was lifted from the salt-cellar on the point of the knife and laid in a small heap on the trencher.

12

Prepared sauces such as mustard, served in open saucers, may have been taken in a similar way. Now the knife was cleaned with a piece of bread, as usual, and set down at the trencher, leaving the thumb and first two fingers of the right hand free to pick up each piece of meat in turn, dip it in the salt or sauce on the trencher, and lift it to the lips.

42.

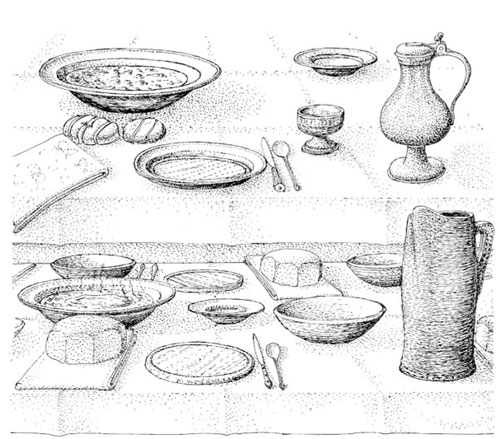

Place-settings

The upper table is set with silver for a noble dining in the Chamber: a wooden trencher is set in his plate, his napkin and a manchet, cut in pieces, are to the left, his cup and wine flagon to the right, and a dish of food and a saucer of sauce before him. In contrast, the servant dining in the Great Hall (below) has a simple ash trencher, a pared cheat loaf and napkin to his left, his wooden drinking bowl and a leather jug of ale to his right, and a mess of pottage and a saucer of mustard ready to be shared with the other three who comprised his mess.

Pies would be eaten in a similar manner. Holding the edge of the crust with the thumb and first two fingers of the left hand, the diner would make one cut from the centre of the pie to the left of his fingers and a second from half an inch (1.3cm) short of the centre to the right of his fingers, then lift the slice on to his trencher. The next diner followed suit, proceeding anticlockwise around the pie, so that no one handled anyone else’s piece and everyone took the same proportion of crust to filling. This precise

information does not come from any Tudor source, however, but from descriptions of late nineteenth and early twentieth century practice in East Yorkshire farmhouses, where good medieval table manners survived intact for centuries. Pennine weavers were spooning up their pottage from communal bowls certainly up to the 1880s, and even within the last few years one could be set at table in some North Yorkshire farms without any cutlery at the place-setting because the personal clasp-knife was still used for eating such items as meat and cheese.

13

Any bones or other debris accumulating on the trencher were deposited in a dish called a voider placed on the table for this purpose. Thus, by constantly cleaning the knife, spoon and trencher with pieces of bread it was possible to eat elegantly, conveniently and cleanly. To those who have demonstrated it over the past decade, it is easy to understand why it remained popular for centuries and why that Italian affectation, the fork, took so long to be accepted by the general body of English society.

43.

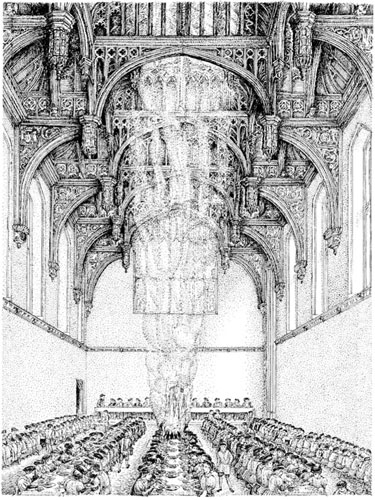

The Great Hall

Bare of tapestries, heated by its central fireplace and buzzing with hundreds of lower courtiers and household servants, this is how the Great Hall appeared at dinner and supper every day, unless it was required for some rare royal entertainment.

Having moved on to the fruit, the Lord Chamberlain and his companions would finally have washed their hands and left the table. Their servants now took their places, and there would be very little left-over food for the almoner to remove from the Great Watching Chamber after they had finished eating.

Down in the body of the Great Hall (no. 40), it is probable that the tables remained standing throughout the court’s stay at the palace, to be dismantled only if this space was required for a great ceremony or entertainment. This may account for the fact that the household regulations state that they were to be brushed clean by two groom ewerers before they laid their cloths. Tables for hall use could be sixteen feet (4.8m) or more in length but only two feet (60cm) broad, since wider tables would not only occupy more space but would also prevent the diners who sat along each side from conveniently eating from communal dishes such as pottage.

14

With fourteen tables of this type, each holding, say, twenty-four people as six messes, the Great Hall could readily seat 336 people in 84 messes, while still leaving room for the waiters and others and for the large central fireplace, its sole method of heating.

Each tablecloth would overhang the edges of the table by some seven to twelve inches (17.5–30cm), and would be changed at least twice a week – more often if soiled.

15

As well as laying the cloths, the two yeomen and two groom ewerers for the hall, assisted by their page, set out the ewers and basins, probably of pewter, and also the linen towels, on a ewery table in an area called ‘the Towel’ close to the entrance screen. Here, while everyone in the Hall was eating too, the groom ewerers for the hall took their meals, along with the other servants who served there, so that they could quickly supply any needs as they occurred. All this was supervised by the marshal of the hall, or one of his ushers, the officers responsible for maintaining good order here.

At each place in the Great Hall a napkin would be provided by the Ewery, along with a cheat loaf set out by the groom or yeoman of the pantry, a trencher in the form of a disc of ash-wood some seven inches (17.5cm) in diameter, with a convex bead turned around its edge, a pewter spoon, and a wooden drinking cup set out by the yeoman of the pitcher house. In addition, the pantry staff would set out a pewter salt cellar to each mess.

16

In theory, the manners and service here, if not the quality and range of the food and drink, should have been as good as those in the Great Watching Chamber. In practice, however, it was much more boisterous, the servants dining here lacking the polish of their superiors. Contemporary descriptions of dining in the Hall, although obviously satirical, provide colourful evidence of the behaviour encountered there.