All the King's Cooks (9 page)

Read All the King's Cooks Online

Authors: Peter Brears

8.

Tudor Lighting

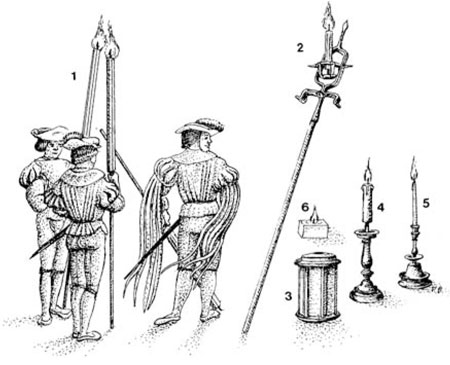

The Chandlery made the long beeswax torches (1) used only for the royal family and nobles (shown in BM Add MS 24098); the shorter ‘link’ (2) was mounted on a long pole for more general use. It also made the candles for wooden lanterns (3), pricket candlesticks (4) and socket candlesticks (5), as well as quarriers (6) – the large square night-lights used for the King’s Privy Chambers and other royal rooms.

Beyond the chandlery, in the corner of the Greencloth Yard on the south side of the inner gateway, a doorway led into the rooms of the clerk comptroller (no. 15). Just opposite, and entered from the gate passage, is a room identified in the 1674 inventory as the Bottle House, but its use in the 1540s is uncertain (no. 17). In 1545 the groom of the bottles was John Mawde, to whom the King had granted the lease of the watermills at Carleton and Burton in Yorkshire.

25

Mawde was responsible to the sergeant of

the cellar for carrying wine in large leather bottles slung from the sides of his bottle-horse, and for ensuring that none was lost or dispensed along the way. Since the storage of beer and wine in glass bottles only began on a large scale in the Elizabethan and Stuart periods, there would appear to have been little need for a bottle house in the palace in the 1540s, and this room probably had another use when first built. It may well have been associated with the adjacent dry fish house and salt store, with which it communicated directly by means of an internal door. Certainly there would have been a great need for such a cool, dark store with no south-facing windows to keep supplies of salt beef, especially during the winter months.

Salt beef formed an important part of the diet of virtually every Tudor household, and it enjoyed a sound reputation. Andrew Boorde wrote:

Beef is good meat for an Englishman so be it the meat be young; for old beef and cow-flesh doth engender melancholy and leprous humours. If it be moderately powdered [salted], that the gross blood by salt may be exhausted, it doth make an Englishman strong, the education of him with it considered. Martylmas beef, which is called ‘hang beef in the roof of the smoky house is not laudable. It may fill the belly, and cause a man to drink, but it is evil for the [kidney-] stone, and of evil digestion, and maketh no good juice.

Salt beef was usually prepared around Martinmas, 11 November, when the cattle were still in good condition after their summer grazing and before they had to be fed on expensive hay and peas. As Thomas Tusser, in his

Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry

(1577), advised:

27

November [for Easter] at Martilmas, hang up a beef,

For stall-fed and pease-fed, play pickpurse the thief.

With that and the like, ere grass-beef come in,

Thy folk shall look cheerly, when others look thin.

The first task when salting beef was to decide whether it was to be dry-salted or wet-salted. The first method involved rubbing a

mixture of common salt, bay salt (a salt with large crystals made by evaporating sea-water by the heat of the sun in the Bay of Biscay), saltpetre (potassium nitrate) and coarse brown sugar into the meat. Plain salt would have tended to dry out the surface of the beef, making it as hard as a board, but mixing it with saltpetre helped the salt to penetrate and gave the beef an appetising pink colour, while the sugar softened it and so counteracted the hardening effects of the salt. When large quantities of salt beef were being prepared, this rubbing and turning process was frequently replaced by wet-salting, for which the meat had only to be soaked in a brine. Wet-salting was certainly carried out at Hampton Court – the palace was provided with ‘ranges for the cawdren to stand upon for the seething and boiling of bryne for the larder’.

28

The beef was first cut up into pieces weighing 2lb (900g) each, which was enough for one mess for four people, and then immersed in the brine as described above, until it was completely impregnated. During this process the salt made it shrink, but, as the Privy Council informed Lord Hertford when he was mounting the 1544 expedition against Scotland, even if this caused the meat to weigh less, it still contained ‘as much feeding, and more, than two pounds of fresh beef when it had been soaked and boiled ready for the table. For storage, the beef was packed into ‘pipes’, large wooden casks of 105 gallons (about 478 litres) capacity, each of which held four hundred pieces, enough to provide 1,600 individual servings.

29

The Pastry Yard

Saucery, Confectionary, Pastry

From the inner gateway, the Pastry Yard looks almost square (no. 19). It is surrounded on the north, east and west sides by Henry VIII’s kitchen offices of 1530–2, while to the south the earlier lodgings of Wolsey’s Base Court extend away eastwards, leaving a wide, open paved passage leading up towards the Great Hall.

This passage was essential for allowing daylight into the lodgings, but it also provided an effective firebreak between the kitchen offices and the main residential part of the palace. More importantly, it provided a direct route for carting such items as barrels of beer down to the cellars beneath the Great Hall and for the bread bearers to carry the manchet and cheat loaves from the bakehouse to the bread room near the buttery; the passage would also have been used to bring the talshides and faggots from the wood-yard to feed the palace’s numerous fires, and the torches, links and candles from the chandlery to provide its illumination. As the main service passage, it must have been a constantly busy thoroughfare, its security ensured by being under constant surveillance from the clerk comptroller’s rooms.

Starting from the inner gateway and proceeding clockwise around the yard, the first door led via a staircase to the offices of the clerk of the kitchen, directly over the gateway, and to those of the

Scullery (no. 20), where the sergeant and two clerks of the scullery and woodyard kept their accounts. The next door gave access to the fish larder, described in the building accounts as the dry fish house (no. 18).

1

As fish was the main fasting-day food, eaten every Friday and Saturday and throughout Lent, it was important that the palace always had supplies ready to hand.

Purchases of fish were made by the clerks comptroller and the sergeant of the acatery, probably with his clerk and John Hopkins, yeoman purveyor of sea-fish.

2

In Elizabeth’s reign these officers were responsible for providing all the ‘ling, coddes, stock-fish, salt-herring, salmon, salt eeles, grey-salt and white-salt’ kept in store in the dry fish house, the yeoman of the salt store delivering them to the main kitchens and larders as required.

3

It made good sense to store the ‘Bay Salt … £20’ and ‘White Salt £13 6 8d’ here in the dry, for they would have deteriorated rapidly in the steamy boiling house and damp wet larders.

4

9.

Ling

This large variety of cod formed the bulk of the salt-fish eaten at Hampton Court.

For the King’s and Queen’s own use there were salt eel, salt lamprey, salt salmon and ‘organ ling’.

5

The latter was the best kind of ling and the largest were caught around Orkney; one writer in 1603 described a superior person as ‘Differing as much from other people … as Stockfishe or poor John from the large organe ling’.

6

Much came into this country from Norway and Iceland, where, Andrew Boorde tells us, ‘the people be good

fyshers, much of theyr fyshe they do barter wyth English men, for mele [meal], lases [laces] and shoes’.

7

Quantities would be carried from the dry fish house into the wet larder a few days before each fish day, to soak there in tubs of water in readiness for cooking in the kitchens.

Next door to the dry fish house, a staircase went up to the first floor to a landing which led left into the pastry and saucery office (no. 21) and right into the confectionary (no. 22). The sergeant and clerk of the pastry, assisted by a yeoman, was responsible for the administration and accountancy of both the main pastry – where pies, pastries and tarts were baked – and the saucery. In the 1674 lodging list the Saucery is located in the hall-side dresser office, but although this is a large room it is unlikely that important officers such as the clerk of the kitchen and his companions would have wished to share their office with a mere yeoman, especially one who was constantly busy grinding, sieving and mixing various odoriferous ingredients, and so the saucery may well have been located elsewhere.

The saucery concentrated on making the thick condiments eaten cold with the meat and fish, rather than the hot sauces made from the internal ingredients of the hot dishes cooked in the kitchens, although the yeoman of the saucery may have helped in their preparation by doing odd jobs such as grating bread. To make the sauces, the Saucery annually purchased ‘in mustard, vinegar and vergeuice [an acid liquor obtained from sour fruit such as crab-apples] £50 … in herbs for sauces, by estimacion £4’, as well as drawing supplies of bread from the Bakehouse, spices from the Spicery, and vinegar made by the Cellar from their ‘feeble or dull wines’.

8