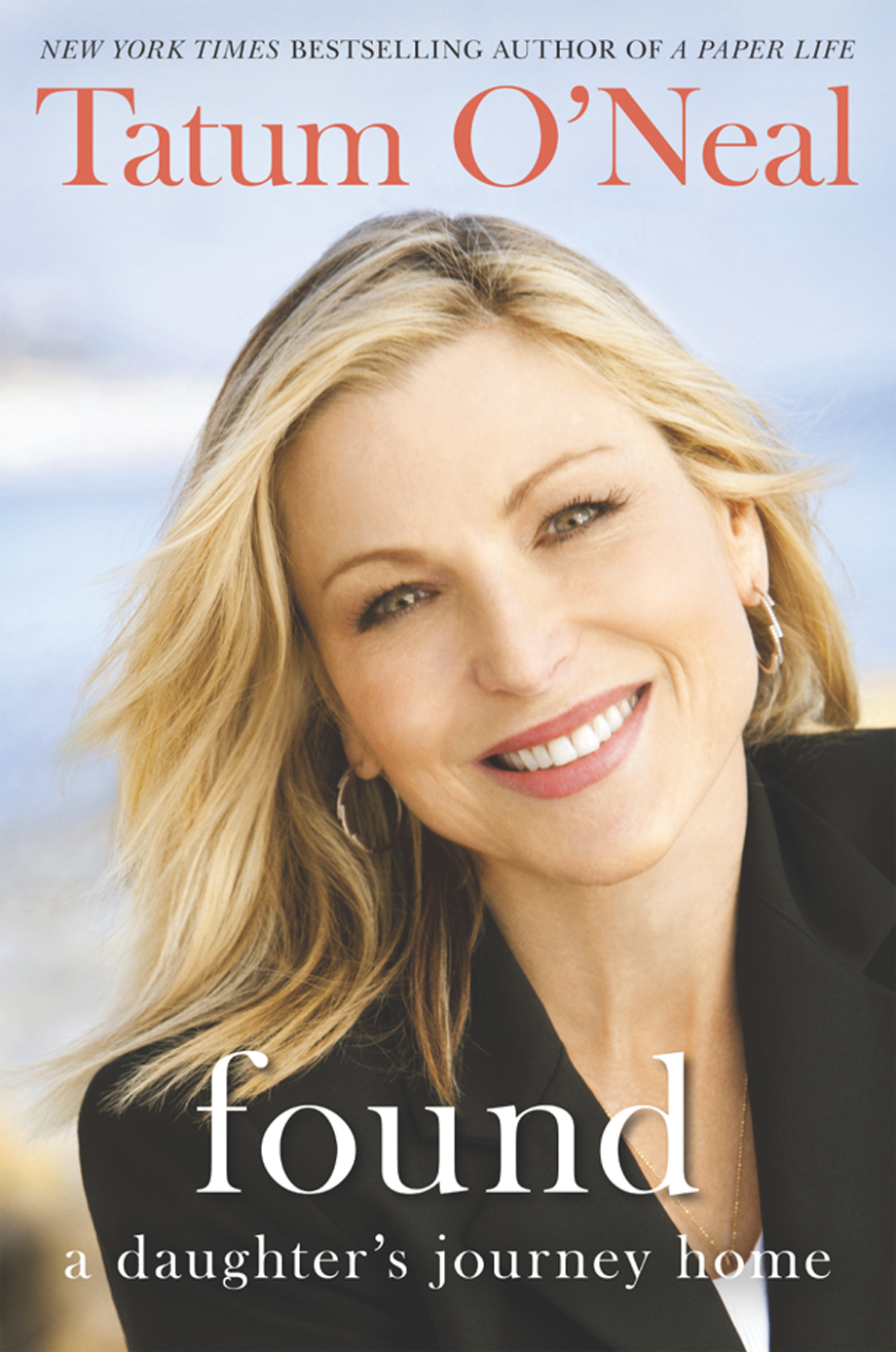

Found

Authors: Tatum O'neal

FOUND

A Daughter's Journey Home

TATUM O'NEAL

with Hilary Liftin

To my children, Kevin, Sean, and Emilyâ

The true loves of my life and the shining stars of my story.

And to my dear friend Perry Mooreâ

You taught me to be a more loving and compassionate

person and I will miss you dearly.

You were a hero.

My dream is to remember to laugh at myself when I've been a fool . . . and to learn from it, and then let it go.

âMy mother, Joanna Moore (1934â1997)

Contents

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

IT WAS SUNDAY

evening, June 2, 2008. My cell phone rang, its familiar ring, as if everything were okay. The same old ring, as if it were still six hours ago, or yesterday, or last week, any time in the past, when this wasn't happening, and the day was sorting itself out the way days always did, with to-dos and phone calls and all the mundanities that add up to a normal life. A cheerful, oblivious ring. Who was calling at this terrible juncture? Was it someone who could help? A friend or ally with a sixth sense for when I was in trouble? Or was it just some random caller, barging innocently into this moment like a bystander strolling onto a movie set? I leaned over as far as I could to see the phone's display.

Emily.

I sank back into my seat, my heart collapsing in on itself. My sixteen-year-old daughter, Emily, was calling, and I couldn't answer. I was breaking my promise to her, and we both knew what that meant.

I WAS AND

continue to be an imperfect mother. My children, like the children of anyone who suffers from addiction, have had to bear the burden of premature knowledge and fear. But my love for them is so strong it can border on obsessive. Always, no matter how I struggled with my own problems, I tried to protect them. I tried to be their mother. I tried to let them be children. But there was a period of time, in the 1990s and the early 2000s, when my sobriety was in flux. My children's connection to me, the connection that makes children feel like nothing can go wrong in the world, was threatened. During that time, if I was using drugs, I could and would go missing while the kids were at John's house. Consequently, I would be unreachable by phone. My phone battery, left uncharged, would die. Or my voice mail would fill up. Or I'd turn the phone off.

One day in 2003, when I was in much better shape, Emily, who was eleven at the time, brought up the matter of reaching me by phone. We were lying in my bed together, her long brown hair fanned out across the pillow. Without looking directly at me, she said, “When you don't answer your phone, I don't know where you are.” She didn't elaborate, but I felt the concern in her tone. She was already mature for her age. She had known from the time she was little to worry if Mom was in the bathroom for too long, to worry if I didn't answer the phone or return her calls promptly.

I was a daughter, too. I was a daughter who needed her mother to be sober. I never got that gift. My mother was a kind, loving woman, my angel, and I have long understood and forgiven her failings, but the truth of the matter is that she never got sober, and I never saw her try. But I did not want that destiny. Not for me, and not with kids.

With every fiber of my being, I wanted my children's experience to be completely different from mine. They were all academic successesâfrom a mother who didn't finish high schoolâbut that wasn't enough. I wanted to be honest with them and to be sober for them. And I wanted to preserve their childhoods. A kid shouldn't be worrying about her mother. She should be wondering what's for dinner, or whether she has the right outfit for the school dance. My addiction was my own problem. My own issue. My own cross to bear. Mine alone. I was bearing it as best I could. I was fighting, and even though my track record was bad, I planned on winning. I was sorry for every point at which my struggles entered my children's lives.

Stroking Emily's hair, I told her I would always answer the phone when she called. I would never turn it off. There would always be a line open.

I'll always have the phone on for you

meant

I'll always stay sober for you

. That was our deal.

I wish it were that simple. God, do I ever.

NOW, FIVE YEARS

later, I was missing Emily's call for the first time since I'd made that promise. I couldn't answer Emily's call, and I knew that she would assume the worst. Rightly so. I had just been arrested for trying to buy crack on a street corner on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. I was in a police station, being booked.

There was a turnstile at the entrance to the jail. Before I went through, someone took my watch, my wallet, and my phone, and put them in a basket. My phone started ringing as they plucked it out of my hand, an audible reminder of my failure. “No!” I wailed, “I've got to get it!” But it was too late. This was jail, baby. I had lost everything.

THIS WASN'T SUPPOSED

to happen. I was supposed to be all better. In the past six years of stability, I'd written a memoir called

A Paper Life

. Writing a book like that was supposed to be cathartic. Ostensibly, if I took all of the suffering and trauma of my childhood and all of the missteps and mistakes of my adulthood and transformed them into little black marks on white pages, then I could literally “close the book” on the past, put it up on a shelf next to my unread copy of

The Great Gatsby,

and never think about it again. Publishing the book was supposed to symbolize the end of one life and the beginning of another. It was supposed to mean that from then on I was clean, healed, and finally free.

Unfortunately, my book contract did not guarantee these results. As it turned out, writing the book wasn't remotely healing. Not at first, anyway. I wrote

A Paper Life

in 2004, after a terrible run in Los Angeles because of which I had lost my kids to my ex-husband. My soul and spirit just weren't strong or sober enough to put it all on paper and move on. Opening up about the things that had happened to me as a child didn't erase the past or transform it to a heartwarming tale of triumph over adversity. That would have been swell. Instead, writing the book was painful. When I summoned the past, it rose to the surface like embedded shrapnel, exiting more slowly than it entered, but still sharp, twisted, and destructive. So much for catharsis.

IN

A PAPER LIFE,

I talked about a childhood in which, under the care of a mother who, in spite of her big heart, was utterly lost to drugs and her own tragedy, my younger brother Griffin and I were left to survive as best we could, living in a run-down ranch in Reseda, California, as little barefoot street urchins whose daily activities included starting fires, playing with knives, and jumping off rooftops. My mother had bought the ranch with the misguided notion that she would save young kids, but it became an unsafe place, harboring teenage runaways and juvenile delinquents. There were drugs and there was criminal activity. My mother had a sixteen-year-old boyfriend, who beat us with switches cut from the fig tree. We were locked in the garage for so long that we ate dog food to quell our hunger. We were unsupervised and wild. My father, Ryan O'Neal, the star of

Love Story,

that golden boy from the big screen, swept in, rescued me, put me in the movie

Paper Moon,

and I was saved. I won a Best Supporting Actress Oscar for

Paper Moon

. I was eight years old when we started filming, and I was nine when I took home my statuette, which made me the youngest Academy Award winner in history. For a while, I was my father's favorite escort around A-list Hollywood. He was brilliantly funny and handsome, and we had a very special bond. But my relief and happiness were short-lived. When I was fifteen and so sadly awkward, Ryan fell in love with beauty Farrah Fawcett and moved to her home in Beverly Hills, leaving me and Griffin alone in his Malibu house to figure out why we had been abandoned by the parent who was supposed to be our savior.

In

A Paper Life,

I talked about my marriage to tennis player John McEnroe, during which we quickly had three children, Kevin, Sean, and Emily, in that order. John eventually lost his number-one ranking, and our marriage crumbled under the weight of his disappointment and my lifetime of trauma. I'd kept my demons at bay during my marriage by running every day, dieting, watching tennis, taking care of the children, and focusing so intently on the external world that I didn't have to face my internal pain and the disease that was inextricably bound to it. They say that addiction, left untreated, does push-ups, getting bigger and stronger while it waits for you to come back and get sucked into it again.

John McEnroe (he was always “John McEnroe” to meâyou know you've got trouble when you think of your own husband by his full tennis champion name) and I separated, then divorced, and he had the kids for two out of every four weeks. I wrote how in their absence my whole world crashed down. A shell of myself, I faced the darkness that had been with me as long as I could remember. I met a boy who introduced me to heroin, which promised to take away the pain, and it was a fast descent from there.

A Paper Life

chronicled a lifelong struggle, and when the press got their hands on it, they looked to me for the lesson learned. Every memoir of trauma and abuse is supposed to have a fairy-tale ending, or, at the very least, an “everything's okay now” ending. I was interviewed by Oprah, Stone Phillips, Katie Couric, and others. What had I gained from this sad, lost childhood? What was the point of the suffering? Where was the triumph over adversity? When was my “aha” moment? I could feel them searching for something I hadn't begun to imagine. The deeper they probed for the requisite epiphany, the more that emerging shrapnel poked brutally at the surface tissue. I felt so raw, so exposed. I didn't have what they were looking for. I didn't have the distance from my life and my disease to step back and see what the message was. I was still too broken.

Nonetheless, after

A Paper Life

came out in October 2004, it appeared to me, my friends and family, and the rest of the world that I was out of the woods. We were all convinced. The book did well. The bitter, heart-wrenching custody battles that had lasted for eight years came to a close, thank God. I had been passing my court-mandated urine tests for years without protest or incident. The only blip on the media radar happened in 2003. I had a drink with a woman, and although I'm not gayâwhat can I say? We made out in a restaurant, and the next morning the cover of the

New York Post

screamed, “Tatum O'Neal's Sapphic Lesbian Love Spree.” John went to court to have my visitation rights revoked, but hallelujah for Judge Silverman! She turned him down.

So, unthwarted by my moment of playing for the other team, I had my children back. My family was stable. I had a long-term boyfriend, an architect named Ron Castellano. I regularly met with my 12-step support group to manage my addiction. Even my acting career was back on track. I had a part on the TV series

Rescue Me,

starring Denis Leary.

And yet, there was my cell phone, the urgent vibrations of its ring making it quiver in the plastic basket on the desk of the police station like a hesitant, terrified mouse.

THE ARREST HAPPENED

on a Sunday at dusk. At the time, I was living in a gorgeous building on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, on East Broadway and Essex. I knew that there was a lot of drug activity around, though I'd never copped drugs in this neighborhood before (and never would again). I was wearing a little T-shirt and black cotton pants, an outfit I had no idea I'd be wearing for the next three days. I grabbed my keys, some cash, and my cell phone, and went out the door and down the stairs. As I stepped outside, I felt an unpleasant shiver of risk, like I was embarking on a creepy, sad adventure, but at no point did I think I should turn back. Once I started out, there was not a chance that I'd turn around. I was propelled by my willâthe part of my will that is controlled by my disease.

Outside, I made two rights, went around the block, and came upon a guy hanging out on a stoop. I could see that he was on heroin, the way drug addicts can recognize one another. Now, a person who was in the habit of using would have been paranoid enoughâor at least careful enoughâto glance over her shoulder to see who might be watching, e.g., the cops. But I'd been totally clean for a year, and it had been six years since I'd been actively using heroin. So, without looking around, I asked the guy if he could help hook me up. He asked me if I was a cop. Slipping right back into a routine from my old using days, I pulled up my sleeve to show him my faded, scarred track marks. (Not proud of those.) He walked to the corner and I followed him. I gave him the money and he took off. I waited for him on Clinton Street and East Broadway. Moments later, he came back holding two small yellow bags.

The minute I took a bag from his hands, several plainclothes police officers appeared out of nowhere and I was surrounded. Before my eyes, an image of my life, the life I'd worked so hard to put back together, sank silently into a pile of gray ash.

Oh shit, it's finally happened.

Why was I so fucking shocked? It's not like I was going to buy some flowers at the corner bodega. This is what happens to drug addicts when they go out and cop drugs. I knew the risk I was taking, and I took it anyway. I'd gotten away with it before, so I thought I was invincible, but now I was getting caught. I was a dumb-ass, not a victim.

“Put your hands up. Show me what's in your hand. Show me what's in your pocket. Put your hands behind your back.” Orders from the police.

I reluctantly unclenched my fist and showed them the drugs. My mind was racing. I reacted like anyone who has ever been pulled over for a speeding ticket or caught shoplifting. I scrambled for whatever words I thought might miraculously change the circumstances. “This is a mistake. You don't understand. This is a fluke. I'm researching a part. I'm not meant to be here. Please.” (Note to drug-copping, high-profile actors: when buying crack in New York City, don't tell cops that you're “researching a part.” They won't buy it. They will tell the press on you. And the press will relentlessly mock you for it.)

Soon I was in a police van, shackled to another person, glad for only one thingâI hadn't actually used. I was utterly, miserably sober. The cops drove me around for a few hours, picking up more people, before we were all brought to the police station.